In preparation for the trial of the assassins, the Honduras Public Prosecutor’s Office extracted thousands of private call logs, SMS, and WhatsApp messages from their phones. The call log evidence was examined by an independent expert, and it showed that the assassins had communicated through a compartmentalized chain that reached the highest ranks of leadership of the company whose dam she had been protesting. Those messages, analyzed below, provide a striking window into the plot to kill Cáceres.

The executives had become angry when Cáceres’s protests disrupted their investment, judges on Honduras’s Supreme Court declared when delivering a guilty verdict in the trial. The executives began surveilling Cáceres and paid informants to infiltrate the organization she led. Then, “DESA executives proceeded to plot the death of Ms. Cáceres,” the court concluded, without naming specific suspects. The plan was carried out with the “knowledge and consent” of other DESA executives, the court stated, again without identifying them by name.

Before and after Cáceres was murdered, in one corporate chat group called “Seguridad PHAZ,” or in unabbreviated English, “Agua Zarca Hydroelectric Project Security,” company leaders discussed using their connections to peddle influence with national authorities, state security forces, and the media. Hundreds more messages, published by DESA’s lawyers, indicate that the company’s president, Castillo, simultaneously maintained regular contact with Cáceres prior to her murder. Although they are a matter of public record, many of the group chats and private messages have never been published.

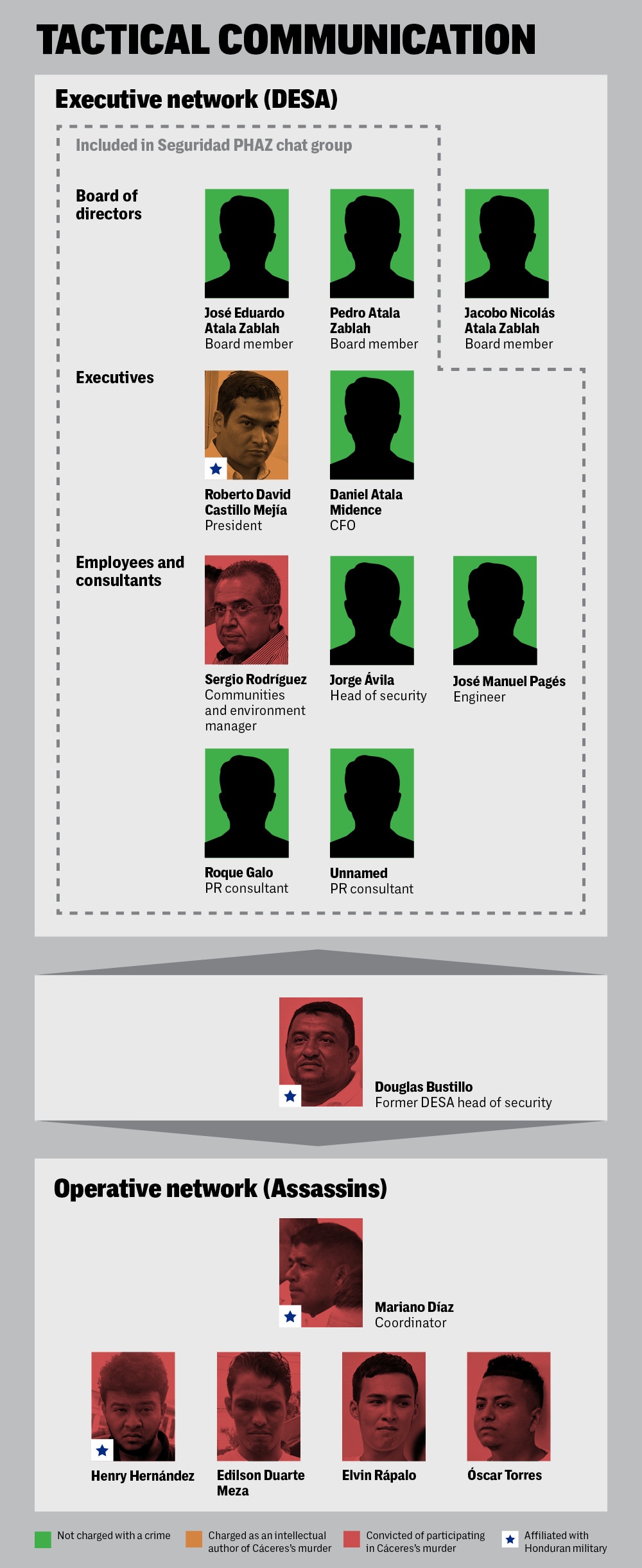

None of the leaders have yet paid for their involvement. Only a group of seven hitmen, including two previous employees at DESA, were convicted in November 2018. On December 2, 2019, the seven hitmen received sentences ranging from 30 to 50 years in prison.

Castillo was arrested on March 2, 2018, for allegedly masterminding the murder, yet the Public Ministry has repeatedly postponed his preliminary hearing. The most recent such delay was on October 10, 2019. Meanwhile, no one from DESA’s board of directors — and no one from the Atala Zablah family — has been charged with a crime or compelled to testify.

Photo: Giles Clarke/Getty Images

Early Duplicity

The “Seguridad PHAZ” group included Castillo, Atala Midence, and DESA board members Jose Eduardo Atala Zablah and Pedro Atala Zablah. The phone number of Jacobo Nicolas Atala Zablah, the family patriarch and another DESA board member, did not appear in the group, but his name was referenced in the messages when business decisions and coordination with high-level allies was needed.

All four Atala Zablah men stood to lose a great deal of money if the company’s proposed dam wasn’t built. As CFO, Atala Midence had devoted his career to Agua Zarca. And Jose Eduardo, Pedro, and Jacobo Nicolas were principal shareholders of Las Jacarandas, the company that held the majority of DESA’s shares. Jose Eduardo was furthermore on the board of directors of the Central American Bank of Economic Integration, the bank that lent DESA $24.4 million to build Agua Zarca.

As their frustration grew in the chats, so did the money the company was willing to invest in halting Cáceres.

On July 15, 2013, the organization Cáceres founded, the Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras, known as COPINH, organized a protest at the site of the hydroelectric dam. Since DESA had not obtained the prior consent of the local Lenca Indigenous community on whose ancestral land the dam was being built, many in the community believed the company had no right to be there.

The demonstration quickly turned violent. DESA had requested that the Honduran army protect the site from the protesters. One of the stationed soldiers used his weapon to shoot a COPINH member named Tomás García.

That day, Atala Midence sent a message to Castillo.

“The military killed an indio,” he reported, using a Spanish slur to refer to a man of Indigenous descent. “It looks like another of them is dead.”

García’s death was a public relations emergency for DESA, but Castillo had a solution ready. “Pay the reporter from HCH,” he responded immediately, referring to a Honduran news station called HCH Televisión Digital.

“1,000 lempiras for last week … and right now we can give him another 1,000.” The total was equivalent to approximately $100.

When HCH ran the story about the protest the following day, the broadcast seemed slanted in DESA’s favor. García’s death was mentioned, but the HCH anchor emphasized the DESA talking point that protesters from COPINH also had blood on their hands: They had killed the child of someone who worked on the dam, he said. But while records show there was a death that day in the community, there is no evidence that members of COPINH were responsible, and they deny having anything to do with it. Meanwhile, the member of the army who shot García has been named and charged.

“You have to call Berta Cáceres, and tell her to stop doing stupid things.”

As Castillo was planning bribes to control the media narrative, he maintained cozy communication with Cáceres. The relationship was strategic, the messages show.

“You have to call Berta Cáceres, and tell her to stop doing stupid things,” an unidentified number told Castillo the day after García’s death. “At this very moment they’re preparing another protest camp.”

Four days later, Atala Midence complained about Cáceres and two other COPINH leaders. “I have spent a lot of money and political capital to get those 3 arrest warrants,” he wrote.

Within days, the three were indicted for illegal land occupation and damages to DESA. An appeals court later overturned the decision and dismissed the charges.

Castillo continued to work hard to build a friendship with Cáceres. Days after sending Christmas greetings in 2014, Castillo reached out again to wish Cáceres a happy new year. He used the opportunity to obtain information about her activities and whereabouts.

He had heard that she had been quite active around the area near the company’s construction site, he texted her.

“When did you come here? And who tells you that?” Cáceres responded with apparent suspicion. But she gave him the information anyway, seconds later: “I’m in Eza. And tomorrow in Teg,” she said, using shorthand for the city where she lived, La Esperanza, and Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras.

Sergio Rodriguez, right, along with six others accused in the murder of Indigenous environmental activist Berta Cáceres, wait after the judges suspended the trial following the filing of a court challenge on Sept. 17, 2018 in Tegucigalpa.

Photo: Orlando Sierra/AFP/Getty Images

“It Could Happen Anytime Now”

In April 2015, Cáceres visited San Francisco and Washington, D.C., to accept the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize for her activism in Honduras. “We must shake our conscience free of the rapacious capitalism, racism, and patriarchy that will only assure our own self-destruction,” she said in her speech. “Our Mother Earth — militarized, fenced-in, poisoned, a place where basic rights are systematically violated — demands that we take action.”

DESA was taking action that year too. Since at least March 2015, Douglas Bustillo, DESA’s head of security and a former lieutenant in the Honduran army, had been communicating with an army intelligence chief, Mariano Díaz. Both were convicted three years later for helping coordinate Cáceres’s murder.

On July 31, Bustillo left the company, but the call log analysis found that he continued to communicate frequently with Castillo, who in turn communicated with Atala Midence, the CFO.

In September, Bustillo called a hitman, Henry Hernández, directly for the first time. Hernández had been a special forces sniper under Diaz’s command.

Meanwhile, communication between Castillo and Cáceres remained active. In the middle of the month, Castillo informed Cáceres that he was going on vacation and would like to speak with her when he returned. On September 28, his comments took a more personal turn. He expressed condolences for health problems in Cáceres’s extended family and told her that she could count on his support.

Cáceres seems to have been puzzled by the texts. “I don’t know why you bother to help me,” she replied. Castillo assured her that he valued her and considered her a friend. “I hope that someday we’ll find common ground in which we can converge our ideals for good and end up with a solution that’s a win for both of us,” he said.

Yet one week later, Castillo was railing against Cáceres and COPINH in the DESA group chat. “We have to take legal actions and bring them before the Attorney General’s office,” he said, suggesting that they should be prosecuted with help from the National Police.

By this time, tensions in the chat had risen tangibly. DESA had moved construction across the river to less-contested territory in an attempt to appease the protesters — but it didn’t work.

The group chat is full of moments when DESA executives discussed recruiting Honduran state security forces and government officials.

It wasn’t the only time that the company snuck into the diplomatic arena. DESA also infiltrated a high-level U.N. visit to COPINH’s headquarters, the chat reveals. The infiltrator posed as a local resident, photographing those present and recording what was discussed.

“It’s them or us,” DESA board member Pedro Atala Zablah wrote to the group on October 11. “Let’s send a message that nothing will be easy for those SOBs.” Jorge Avila, who had taken over from Bustillo as DESA’s head of security, responded by asking Atala Zablah to order police protection for the dam.

This was a common move; the group chat is full of moments when DESA executives discussed recruiting Honduran state security forces and government officials. Sometimes, it was members of the Atala Zablah family — Daniel and Pedro — who made the requests. On October 13, Pedro suggested that DESA could motivate police officers “with something more than food.” The company already housed and fed the police who guarded the dam as they might do for private security.

The day after those texts were sent, Castillo reported to the group some news about Cáceres: She was leaving for South America soon, and the time was ripe to whip up local opposition to her organization. DESA’s communities and environment manager, Sergio Rodriguez, observed that COPINH’s movement was weaker when Cáceres and another leader weren’t around. “Given that, we should also direct actions against them,” he posed to the group.

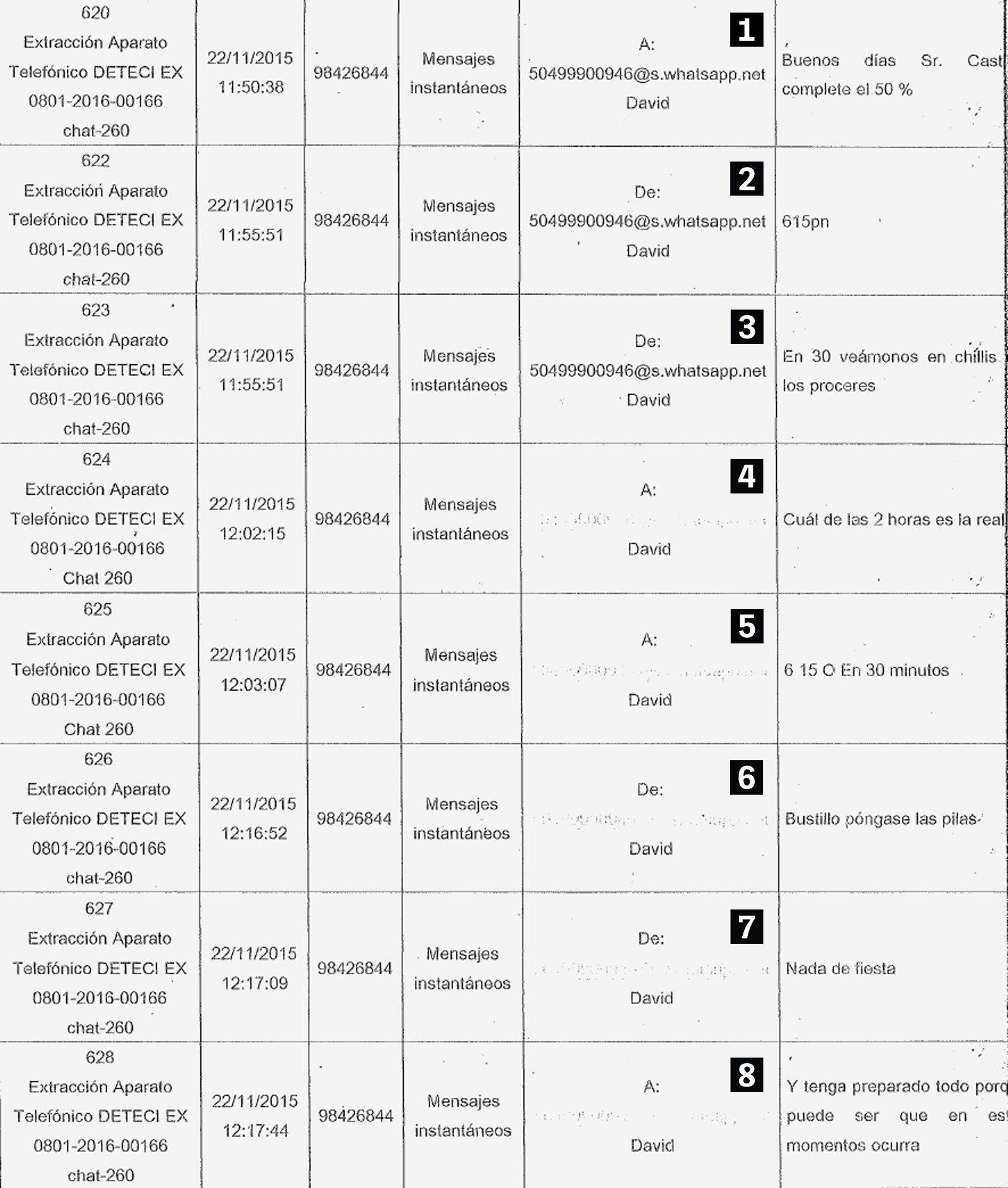

Document: Honduras Supreme Court

On November 22, Castillo received a message from Bustillo, who had not worked for DESA for four months. “Good morning Mr. Castillo. Give me the 50 percent,” the cryptic message read.

Castillo responded by asking to meet Bustillo later that afternoon at a Chili’s restaurant in a wealthy part of Tegucigalpa. He suggested two different times for the meeting, and when Bustillo asked for clarification, Castillo snapped: “Bustillo, get your act together. This isn’t a party.” Bustillo retorted: “And you get everything ready, because it could happen anytime now.”

The men didn’t specify what they were discussing. But the call log analysis prepared for trial shows that by this time, the company had assembled a compartmentalized communication method, likely due to the “high degree of specialization of the military personnel that makes up this structure,” the analysis stated.

Graphic: The Intercept; Photos: Getty Images

“Compartmentalization is a tactic established in military intelligence to avoid infiltrations and to not compromise the ensemble of information and structure,” the analysis reads. “Decision-making is reserved for only the maximum leadership level. … It is a tactic to proactively hide the entire criminal cycle.”

Castillo and Cáceres’s personal communications continued, however, and the two ended 2015 exactly as they had the year before. On the night of December 25, they exchanged pleasantries.

“Dear Berta,” Castillo wrote. “I hope you and your family have a blessed Christmas holiday. Like always, I wish you only the best.”

“A Pain in That Lady’s Butt”

By January 10, 2016, Castillo was back to agitating in a DESA chat.

“We can’t let our guard down. But it’s this week that we must overcome COPINH. Our efforts this week will bear fruits and our work will be easier during the remainder of 2016,” he said. He then forwarded to the group a note he had sent a local police commissioner, whom he seemed to consider an ally.

“We thank you for the support that you gave us yesterday, the Copinhnes saw the presence of the National Police … and they were afraid to cross the river,” the note read. “I hope to count on your support today and the remainder of days until the agitator leaves, which is when the threat ends.”

When two new foreigners from the Netherlands began showing up at COPINH protests, DESA investigated them too, chats from late January show. “Please take photos,” the company’s public relations consultant Roque Galo said. He suggested that they use the company camera with the best zoom capability. Galo has not been charged with a crime related to Cáceres’s murder.

Two days later in private messages, Díaz and Hernández discussed a different kind of technology: a borrowed gun. “I don’t want you to be carrying that thing all over the place,” Díaz said to Hernández. “It’s dangerous and you could get in a mess.”

On February 2, Hernández, who referred to Díaz as “señor,” laid out a strategy to shield Díaz from suspicion: “I’m going to work with other guys, sir, because you have to be clean so that everything goes well for you in your career,” he wrote. He asked Díaz to loan him enough money to hire two others so the three of them could carry out “the job.” He clarified, “You know which one.”

They did not name the people who hired them for “the job,” but referred to them as “friends.” Nor did they name their target.

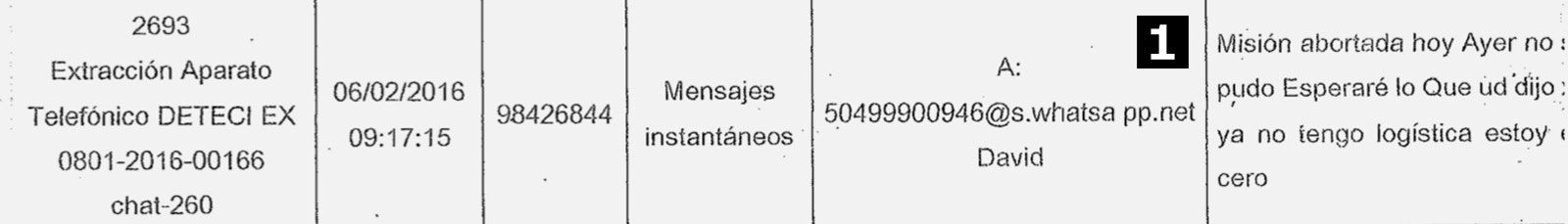

Document: Honduras Supreme Court

On February 5, Bustillo used his phone to download three photographs of Cáceres’s face. One was an image that would later go viral. Cáceres stands flanked by the green banks of the river she worked to protect, her mouth open in speech, her right hand raised.

That same day, messages and calls flew among the hitmen, call analysis produced for trial shows. The analysis also shows that Hernández’s cellphone pinged off the towers near Cáceres’s house.

The chats suggest that Hernández and an unknown second hitman attempted to kill Cáceres that day, but called the mission off because there were too many people near her home. They grabbed public buses and left the area.

“Mission aborted yesterday,” Bustillo wrote to Castillo. “It wasn’t possible. I’ll wait for your reaction. I don’t have the logistics in place anymore, I’m at zero.”

Later that day, Bustillo asked Castillo for more money to pay for a second attempt. “Boss,” he said. “I need to know your budget for the job.” Three weeks later, Bustillo repeated the request. Castillo responded that he himself wouldn’t be paid until the next day.

Meanwhile, the participants in the chat group continued disparaging Cáceres. On February 20, an unidentified public relations consultant hired by DESA, who has not been charged in connection with the case, celebrated having complicated COPINH’s plans for a protest. “It’s so great that we’re a pain in that lady’s butt,” he wrote.

Lead engineer Pages responded that they should publish photos of Cáceres’s home and car, and the fact that she had children studying in foreign countries, to turn activists against her. He informed the group that the company could expect 45 police and members of a U.S.-trained special forces group known as the TIGRES to guard the dam site during a protest.

In a discussion about media coverage of the event, Castillo wrote: “Instead of asking a journalist not to publish an article, I think it’s better to give them instructions about what they should include in their article and what message to give.”

In less than a month, Berta Cáceres would be dead.

Murder, Preserved in the Messages

On March 2, 2016, the hitmen decided to try again. The cell analysis produced for the trial showed their phones pinging repeatedly off the cell tower near Cáceres’s house.

Document: Honduras Supreme Court

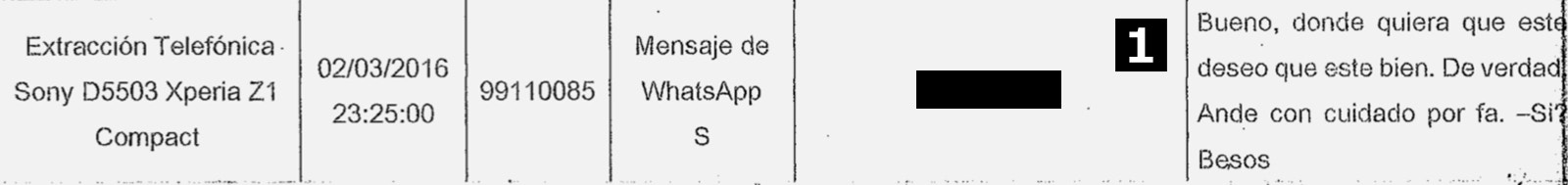

At 11:25 p.m., Cáceres sent her last WhatsApp message. “Well, wherever you are, I hope you’re well. Truly,” she wrote a friend at an unidentified number. “Be careful please, OK? Kisses.”

Simultaneously, the triggermen and Bustillo were trading a flurry of messages and calls.

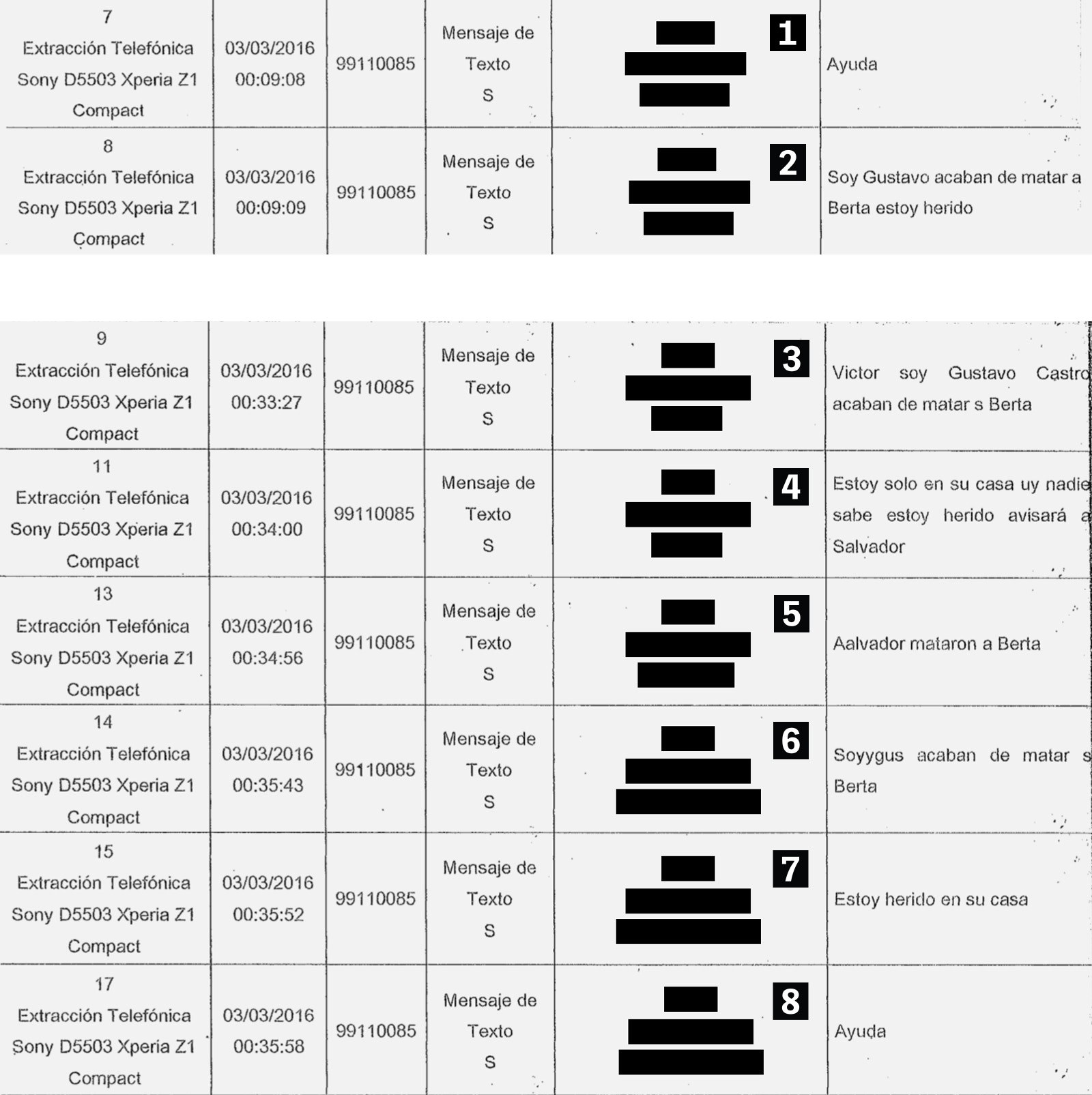

Fourteen minutes later, at 11:39 p.m., Gustavo Castro, a visiting Mexican environmentalist who Cáceres was hosting in her home that evening, began making desperate, unanswered calls from Cáceres’s phone to those closest to her.

Document: Honduras Supreme Court

At 12:09 a.m., he sent a message to a member of Cáceres’s family: “Help.”

“This is Gustavo. They just killed Berta. I’m wounded.”

Anguished messages followed, the same details repeated over and over again, receiving no response:

“Help.” “It’s Gustavo. They just killed Berta.” “I’m alone in her house and no one knows.”

“Please tell COPINH.” “Some neighbor or some contact in La Esperanza.”

At 5:37 a.m., the DESA chat lit up.

Sergio Rodriguez was the first to send a news clipping of her death. Twelve minutes later, Castillo messaged the group too. “For us, this is a crisis. We should anticipate what’s coming at us.”

Photo: Orlando Sierra/AFP/Getty Images

A Bureaucratic Stalemate

After Cáceres’s murder, as public rage flamed at the company, the chats show that DESA executives scrambled to seek help from their powerful allies.

On March 7, 2016, the Honduran minister of security, Julián Pacheco Tinoco, assured Pedro Atala Zablah that Cáceres’s death would be categorized as a “crime of passion.”

When throngs of protesters started congregating at the site of the dam, Pages asked Atala Midence to speak with an infamous police commissioner named Héctor Iván Mejía to request more officers to confront them. Atala told Pages that he had already spoken with him, along with Pacheco Tinoco.

By April 1, when the Honduran government announced an investigation into the murder, the unidentified PR consultant tried to lift spirits in the DESA chat. “The Public Ministry until now has been an ally and not an enemy,” he wrote. “We have to think strategically, that what’s possible and most likely and truest is that the Public Ministry said this to hush up COPINH’s finger-pointing.”

It was best for DESA to remain quiet about the murder, he advised, because if the company publicly criticized the Public Ministry’s case, “it would call into doubt the Honduran authorities’ investigation process and that would considerably increase the finger-pointing against us.”

Later that month, DESA’s head of security, Avila, reported to the group that his military intelligence sources had warned him of COPINH’s plans for another protest. Pages suggested that they work with police to intimidate protesters by recording their names and vehicle plate numbers. Shortly after that, Rodriguez said he had tasked the company’s infiltrators in COPINH to spread rumors to divide and weaken the organization.

Among the data that prosecutors extracted from Rodriguez’s phone is a file dated March 3: a photograph of Cáceres lying sprawled on the floor, one arm jutting out at an odd angle, the other covered in a pool of blood. Her mouth is open, her hair swirled above her head.

In response to a request for comment, Nelson Dominguez, attorney for Daniel, Pedro, and Jose Eduardo Atala Zablah, stated that the men “completely deny any participation in this unfortunate crime” and “firmly believe in the innocence of Mr. David Castillo and Mr. Sergio Rodríguez.”

DESA’s telephone number and email address are no longer in service. Robert Amsterdam, who said his firm Amsterdam and Partners LLP represented DESA until months ago but is no longer retained by the company, maintains that his former clients were not involved in the murder of Cáceres. “These were idealistic young men who wanted to rid Honduras of their dependence on gas and wanted to set up a sustainable situation,” he told The Intercept. “They’ve put absolute innocence behind bars and in that, I’m talking of Castillo.”

Amsterdam outlined the company’s defense in a white paper published in 2018, titled “War on Development: Exposing the COPINH Disinformation Campaign Surrounding the Berta Cáceres Case in Honduras.” The white paper suggested that cellphone data presented in court could be “incomplete or corrupted.”

Dominguez repeated this claim. He wrote that the Atala Zablah family had filed a legal complaint with the Public Ministry for “manipulation of evidence” and claimed “grave violations of the right to due process.”

Yuri Mora, a spokesperson for the Honduran Public Ministry, responded: “These are arguments and strategies by the Defense. The Public Ministry is sure of its accusations and all of the evidence.”

Galo, Mejía, Pages, and Pacheco Tinoco did not respond to requests for comment.

Castillo’s fate remains unclear. If his trial is delayed too long, he may be released from prison because of a Honduran law that prohibits holding individuals who haven’t been convicted for longer than two years. Meanwhile, an investigative dossier published this past August by the human rights group School of the Americas Watch revealed alleged chronic criminal activity Castillo committed on behalf of at least six Honduran corporations with which he was involved, including DESA, and possible links to a major drug cartel. That same month, journalist Nina Lakhani of The Guardian revealed Castillo’s purchase of a $1.4 million home in Texas eight months after Cáceres’s murder.

But Roxanna Altholz, a professor at Berkeley Law and former member of GAIPE, an international team that investigated the murder, says the problem is bigger than the lack of progress on Castillo’s case. The larger issue, she says, is that Cáceres’s murder was the culmination of years of coordinated corruption and violence. The illicit network responsible, including the Atalah Zablah executives at DESA and their allies, remains intact.

“Accountability isn’t fulfilled with a guilty verdict of any of these individuals,” she said. “In order for there to be accountability in this case, that criminal network must be dismantled.”

Danielle Mackey | Radio Free (2019-12-21T13:00:43+00:00) Inside the Plot to Murder Honduran Activist Berta Cáceres. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2019/12/21/inside-the-plot-to-murder-honduran-activist-berta-caceres/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.