The suit brought by Montrevil, 51, a founding member of the New Sanctuary Coalition of New York City, builds on a significant ruling last spring by the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals in the case of a former colleague, activist Ravi Ragbir. In Ragbir’s case, the court found that ICE’s moves against Ragbir in early 2018 were intended as retaliation for Ragbir’s political speech and thus, violated his rights under the First Amendment.

“It’s only once he began speaking out as an activist that his real problems with ICE began.”

“Since 2005, Jean was, like nearly a million other people, living under an order of supervision, which allowed him to live in the U.S. with authorization,” said Lauren Wilfong, one of the advocates representing Montrevil. “It’s only once he began speaking out as an activist that his real problems with ICE began.”

Montrevil’s friends and family describe the trajectory of his life as precisely the sort of story of redemption and growth that is demanded of people convicted of crimes. They say his adult life was characterized by the industry, community building, and love that this country valorizes in its immigrants. In their eyes, Montrevil’s deportation is a double-jeopardy punishment for youthful crimes he long since served time for. Even more troublingly, it is punishment for daring to raise his voice to call attention to the violence and injustice of America’s immigration enforcement apparatus. Montrevil’s lawsuit is seeking to make the court recognize what seems plain to many who have followed his case: that his deportation was, at its essence, political — the literal banishment of a dissident who challenged the government too often and too loudly.

Montrevil came to New York legally in 1986, at the age of 17, when his father, a former Haitian military official living in Brooklyn, obtained a green card for him. For Montrevil, who had grown up fending for himself in Port-au-Prince, the transition to living under the stern authority of his father was difficult. “It was a bit of a shock,” Montrevil told The Intercept from Port-au-Prince. “He was very tough, you know, ex-military. It was hard for me to get along with him. Looking back, I blame myself for not listening.”

Montrevil ran away from home and, in his telling, fell in with the wrong crowd. Over a two-year period, he racked up convictions for drug possession with intent to distribute in Virginia, a gun possession misdemeanor in New York, and a federal drug possession conviction in New Jersey. In jail awaiting trial on his Virginia charges, Montrevil got in a fight, leading to further charges. In 1989, with the war on drugs in high gear, mandatory-minimum sentences dictated meting out lengthy prison stays. At the age of 21, Montrevil was staring down a 30-year sentence. As a legal permanent resident, his convictions also made him deportable.

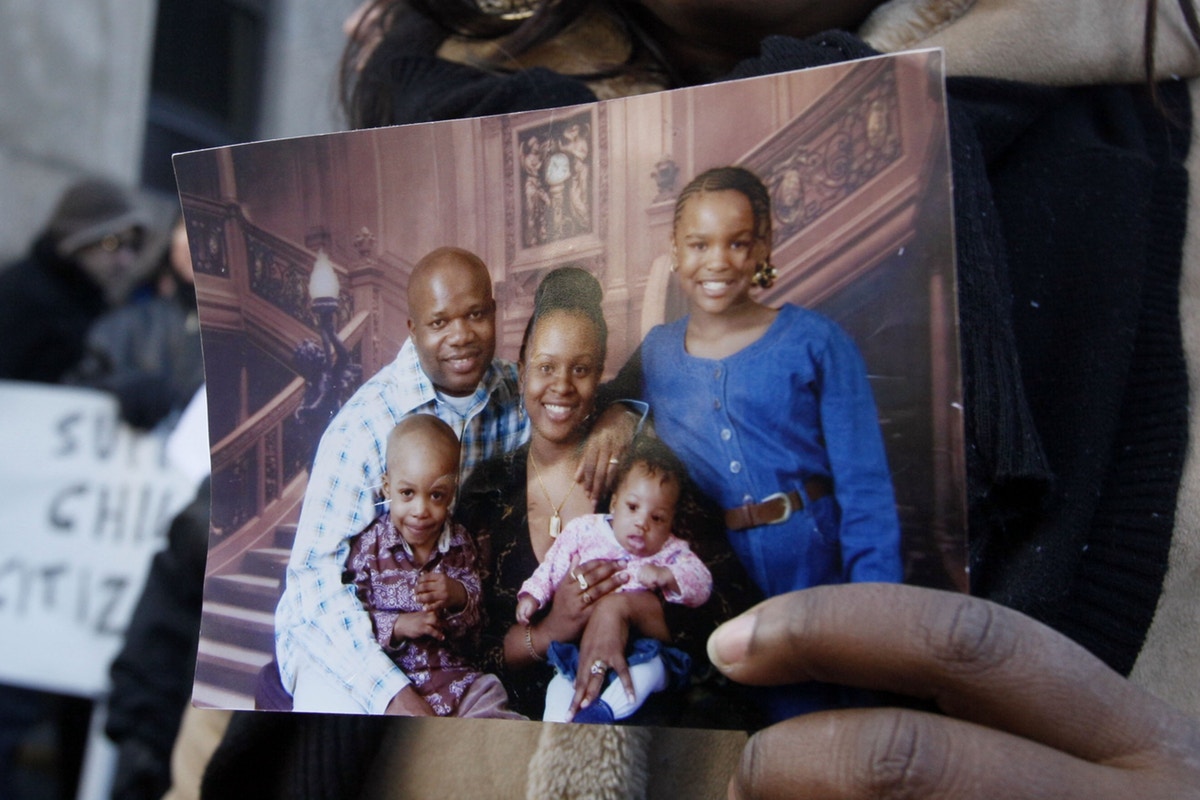

When he was released on parole in 2000, Montrevil was 32 and determined to lead a different life. He took up management of a religious goods shop in Flatbush, Brooklyn. He met Jani Cauthen, a public-school aide, and they got married and had children. He scrupulously kept to the terms of his parole and checked in regularly for his scheduled appointments with immigration authorities. He volunteered with HIV patients through his church. And he began working with Families for Freedom, an organization that offers support to detained immigrants and their families.

Juan Carlos Ruiz, a Lutheran minister and immigration activist, met Montrevil through his work with Families for Freedom, and invited him in 2006 to help found what would become the New Sanctuary Coalition of New York City. Where Families for Freedom focuses its work on serving people caught up in the machinery of deportation, the New Sanctuary Coalition would be more outward-facing, more political, and more high-profile. “Jean didn’t let his fears stop him, but of course, he was concerned about the risks of becoming a public face of the movement,” Ruiz said.

Those concerns proved well-founded. As Montrevil’s new role put him in the media spotlight, ICE responded with what he took to be retaliation. Within a year, the agency enrolled him in the Intensive Supervision Appearance Program, or ISAP, which was more ordinarily reserved for people who had failed to keep their scheduled check-ins or were otherwise considered a flight risk. Montrevil was required to wear an ankle monitor, check in with ICE three times a week, and keep a curfew of 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. Though most people at the time were placed on ISAP for short periods of time, Montrevil was kept on the program for more than a year. The curfew crippled his new business, using a van to drive customers to airports or visit relatives upstate. The electronic shackle irritated his skin, leaving scars that he still wears today.

ICE was definitely aware of his political activism, Montrevil said. At a check-in in December 2009, as he was taken into custody as a prelude to deportation, an ICE officer referred to his media profile, calling Montrevil the “one complaining to the Village Voice.” As Montrevil waited in a Pennsylvania prison, his family, church, and supporters rallied round him, flooding ICE’s New York Field Office phone lines and getting themselves arrested in noisy protests outside. “There’s no question in my mind that Jean was being targeted for speaking out,” the pastor of Montrevil’s church, Rev. Donna Schaper, said.

Montrevil was ultimately released, but he was given a stern warning from high up. In an unusual step, Christopher Shanahan, then the director of ICE’s New York City Field Office, met with Montrevil, Schaper, and Montrevil’s lawyer, Joshua Bardavid. “This can’t happen again,” Shanahan said, according to Schaper. If Montrevil would agree to lay low, Schaper said Shanahan told them, he wouldn’t have any more problems. Montrevil said that Shanahan even told him that if he kept his head down, the ICE New York director would himself look into getting Montrevil deferred-action status, giving him lasting protection from deportation.

Shaken, traumatized, and worried about what would happen to his family if he continued to antagonize ICE, Montrevil decided to take Shanahan’s suggestion and step back from his activism. He stopped giving interviews and focused on his business, his church, and his family. Seven years went by, and Montrevil kept his periodic appointments with ICE without incident.

In 2017, President Donald Trump was elected on campaign promises to get tough on immigrants. Montrevil decided to take part in one of the New Sanctuary Coalition’s prayerful demonstrations outside the local ICE headquarters. At his next check-in, Montrevil was detained, fingerprinted, and asked to turn over his property. Bardavid, his lawyer, showed ICE officials a paper receipt demonstrating that Montrevil still had a motion pending with the Board of Immigration Appeals, but ICE insisted that it had no records of any open proceedings in its system. And then, as suddenly as his check-in had escalated, Montrevil was released without explanation. “They just told me it had come from ‘upstairs,’” Montrevil said. “I think they were trying to scare me.”

“One of the guys said to me in the car, ‘Don’t you know we have Trump as president now? He doesn’t like immigrants.’”

Montrevil was given another check-in date on January 16, 2018, but ICE never intended for him to keep it. Sworn statements by ICE officials in Ragbir’s case later revealed that they had begun planning Montrevil’s and Ragbir’s deportations in October. Though they initially denied it, ICE officials later admitted that they put Montrevil, Ragbir, and the offices of the New Sanctuary Coalition under secret surveillance.

On January 3, plainclothes ICE officers — who evidently knew that Montrevil regularly returned home on his lunch break — arrested him near his house in the Far Rockaway area of Queens as he was returning to his car. Montrevil was taken to the local ICE office at 26 Federal Plaza in Lower Manhattan

“One of the guys said to me in the car, ‘Don’t you know we have Trump as president now? He doesn’t like immigrants,’” Montrevil said. “I kept telling them I have a motion pending. They said, ‘Anything you have pending, it’s been revoked.”

At the ICE office, Montrevil repeatedly asked to speak with his lawyer but was told that his lawyer wasn’t in the building. In fact, Bardavid was in the building, but was being told that he couldn’t meet with his client. ICE moved Montrevil to detention in New Jersey but kept Bardavid in the dark at 26 Federal Plaza all afternoon, telling him that he could meet his client the next day.

Bardavid finally spoke with Scott Mechkowski, then the deputy director of ICE’s New York Field Office, on January 5. “We war-gamed this over and over,” Bardavid recalled Mechkowski telling him, of Montrevil’s detention. What Mechkowski didn’t tell Bardavid was that ICE was moving his client that very day to the Krome Detention Facility in Florida. Montrevil’s outstanding paperwork was resolved over the long holiday weekend of Martin Luther King Jr. Day. By the time court opened at 8 a.m. the following Tuesday to consider Bardavid’s emergency petition, Montrevil was on a plane to Haiti that had taken off at 7:38 a.m.

“ICE planned and executed Jean’s removal in a way that would prevent him from accessing counsel and the courts,” Bardavid concludes, in a sworn declaration attached to today’s lawsuit.

Montrevil’s advocates in his new lawsuit, Wilfong and Diana Rosen, students in New York University Law School’s immigration law clinic, said the legal and civic issues at question in Montrevil’s case are critical. There are dozens of other documented instances around the country of immigration activists being targeted for deportation. “This is an ongoing harm, and ICE clearly feels they can act with impunity to silence their critics,” Rosen said. “In deporting Jean the way they did, ICE sought to send a chilling message to immigrants who might exercise their First Amendment rights. What’s at stake with this case is really whether they’re successful in that or not.”

For Montrevil and his family, there are more personal stakes as well. Montrevil said he is having a tough time in Haiti, a country he left as a boy, where conditions are deteriorating rapidly. His oldest child with Cauthen, Jahsiah, is now 16 and a junior at the prestigious Brooklyn Technical High School, but since his father’s deportation, he has been struggling and the family is worried about him. Montrevil’s daughter, Jamya, said she talks to her father each day over WhatsApp, when Haiti’s unreliable communications infrastructure permit, but that it’s not the same as having him present in her life. “I thought he was going to come back, but he never actually did,” she said. “I wish people understood: When you deport someone, it doesn’t only affect one person, it affects their families too.”

Nick Pinto | Radio Free (2020-01-16T14:00:23+00:00) “Targeted for Speaking Out”: Deported Activist Files Free-Speech Suit Demanding Return to New York. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2020/01/16/targeted-for-speaking-out-deported-activist-files-free-speech-suit-demanding-return-to-new-york/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.