In January, as the president insisted the novel coronavirus posed no threat to the United States, Tupelo, Mississippi, Mayor Jason Shelton nervously eyed the grim reports filtering out of Wuhan, China. Shelton had planned a spring vacation in Europe with his pregnant wife. “A babymoon,” the second-term mayor said recently. “The new, trendy thing.” But Shelton and his wife, a nurse practitioner, didn’t like the news from China. They decided the risk of a pandemic spreading to Europe was too great and canceled the trip.

Since then, Shelton has placed Tupelo, population 38,000, in the vanguard of the fight against Covid-19. There were only a few dozen cases in the U.S. when he penned his first executive order in late February, appointing his fire chief to monitor the risk, and on March 22 he issued a decree ordering people to stay home.

Shelton badgered Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves to follow suit for days. When the governor first acted, he classified almost all the state’s businesses as “essential” in an order that threatened to override tighter local rules — until Reeves “clarified” under criticism that local orders could stand.

Throughout the South, Republican governors have followed President Donald Trump’s lead in resisting economic restrictions and orders to stay home. Meanwhile, mayors and local leaders, most of them Democrats, have heeded warnings from public health experts — and in Shelton’s case, his wife — to shut their cities down anyways. As case counts grew, governors tussled with mayors over the extent of local authority, sometimes reversing city orders and even reopening churches.

The result has been a patchwork map of local restrictions that reflects the entire nation’s haphazard response to the coronavirus. While several Southern governors changed their tune after Trump warned of a massive death toll on March 31, health experts worry that precious time has been lost in a region where high rates of underlying health conditions like diabetes, and shocking mortality rates for African Americans, have already translated into high death tolls in areas with early outbreaks.

“What you have is the perfect storm: people that are already marginalized socially, people that have fewer economic resources and states that have fewer resources,” said Thomas LaVeist, dean of Tulane University’s School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine. “I’m very fearful.”

Photo: Hyosub Shin/Atlanta Journal-Constitution via AP

The coronavirus was ripping through the country and infecting thousands of people every day when University of Georgia students returned from spring break in mid-March. Athens-Clarke County Commissioner Russell Edwards watched in horror as they kept the party going. “They were throwing keggers at the frat houses. It was a mess,” Edwards said.

Edwards proposed a curfew and a countywide ban on public gatherings. But other commissioners watered down his restrictions to apply them to bars, streets, and restaurants only, and rejected outright the curfew, saying they weren’t sure they could act in the place of Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp.

An outbreak was exploding in Georgia’s Dougherty County, which now has one of the highest death rates in the country, but Kemp refused to issue an order locking down the entire state. He insisted that voluntary social distancing would work and expressed fear of the economic fallout.

“We start putting more people out of work, it creates revenue issues for the cities and for the counties and for the state,” Kemp said last month. “We literally could have people losing everything they’ve worked their entire career for.”

His chief of staff went even further on Facebook, accusing local governments of “overreacting” and bemoaning “doomsday” death projections.

Many Republican governors in the South likewise said their case counts weren’t high enough to justify broad economic bans, even while admitting that their testing was spotty. So as the national case count skyrocketed in March, local leaders in the South stepped into the void in leadership.

On March 20, Edwards succeeded in convincing Athens-Clarke County to pass a stay-at-home order modeled on one issued in the San Francisco Bay three days before.

On March 22, Tupelo imposed the stay-at-home order within its city limits. Shelton begged Mississippi’s governor to follow suit.

On March 26, two days after Trump said he wanted the country “raring to go by Easter,” Columbia Mayor Steve Benjamin ushered in a stay-at-home order for South Carolina’s capital city.

But GOP governors were reluctant to institute these measures statewide. Many backed weak restrictions or voluntary social distancing instead. By March 30, the trend was clear; of the 11 former Confederate states, only the three with Democratic governors issued firm stay-at-home orders.

Edwards speculated that the resistance to strong preventative measures was out of fealty to Trump. Kemp, he said, acted in “lockstep” with Trump on the virus threat. “You’ll see Brian Kemp retweeting everything Trump says. You’ll see him praising Trump at every last opportunity,” Edwards said. “I don’t know what’s going on in Brian Kemp’s head. But it has the appearance that he’s simply Trump’s lackey.”

Benjamin, the mayor of Columbia, South Carolina, said he faced some resistance from business leaders, but was confident that stay-at-home was the right move after consulting with hospitals. “It was clear, looking at the data, that this was going to be a Cat-5 storm hitting everyone at the same time,” Benjamin said.

Not everyone got the weather forecast. Some Republican state officials weren’t content to simply stand by while mayors one-upped them. Instead, they intervened to reverse local restrictions.

After Benjamin passed the Columbia order, South Carolina’s attorney general issued a legal opinion that only the governor had the authority to force people to stay cooped up inside. Gov. Henry McMaster praised the legal opinion and one city briefly tabled its plan for a stay-at-home order.

Benjamin announced that his city’s order was going to go into effect on a Sunday regardless. He added that he was prepared to defend it in court that Monday.

“In moments of crisis like these, clarity is so important,” Benjamin said of his public stand.

After that pushback, the attorney general relented, saying he never had any intention of going to court. But other state elected officials have been more aggressive in reversing local restrictions.

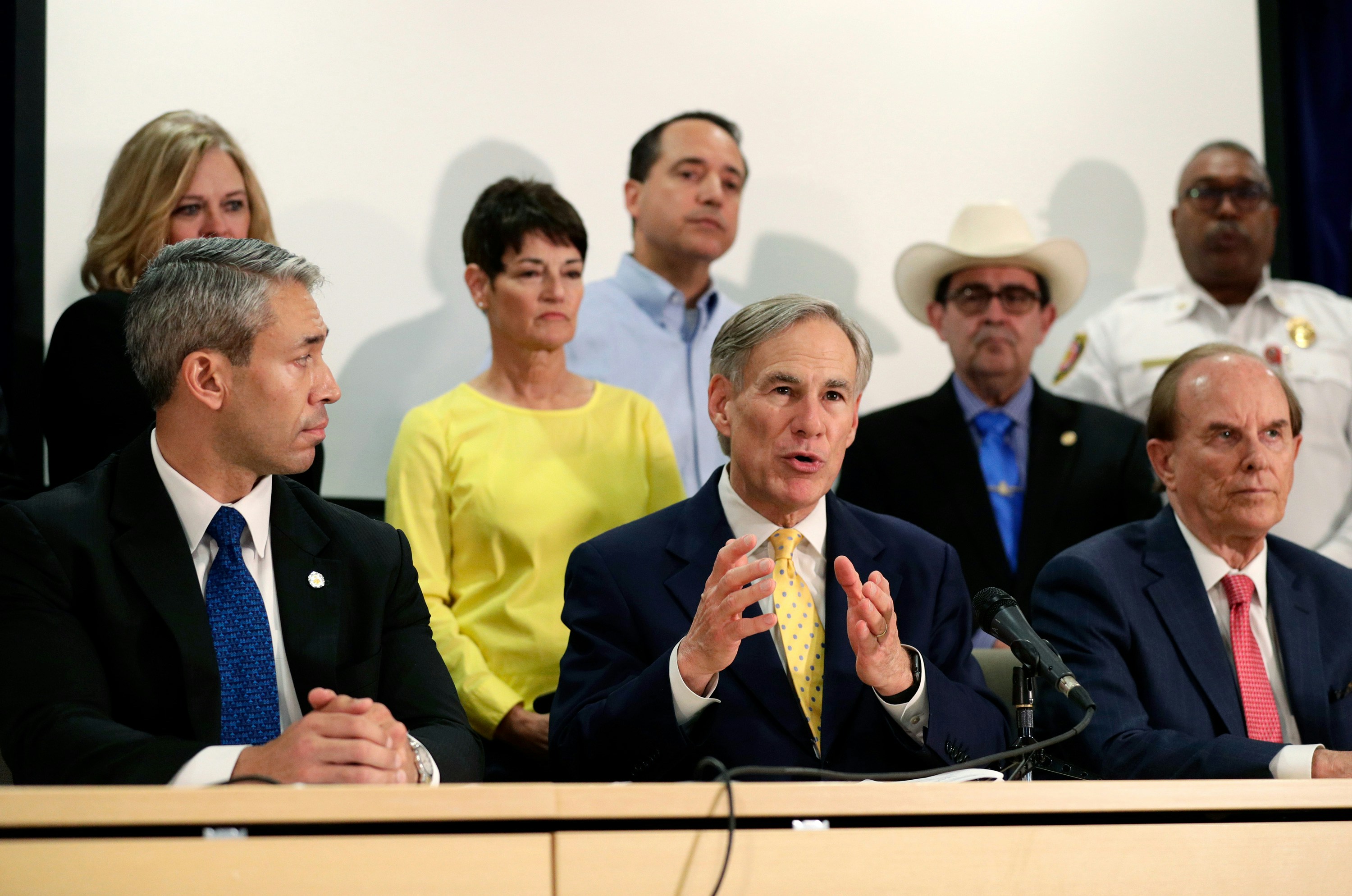

Photo: Eric Gay/AP

Churches have been a flashpoint. In some states, influential megachurch leaders have kept holding mass services despite the risk to their parishioners.

After Trump announced on March 31 that the U.S. might see 100,000 to 240,000 deaths from the coronavirus, Southern states’ resistance to strict orders to stay home collapsed. Texas’s order went into effect on April 2; Florida, Georgia, and Mississippi’s orders on April 3; Alabama’s order on April 4 and South Carolina on April 5. Arkansas is now the lone holdout in the old Confederacy.

But several governors have overridden local leaders and exempted churches from their lists of nonessential businesses that must close. Texas and Florida’s governors have allowed churches to continue holding services.

“There is no reason why you couldn’t do a church service with people ten feet apart,” Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis said. “In times like this, I think the service that they are performing is going to be very important to people … particularly coming up in the Easter season.”

In Texas, San Antonio Mayor Ron Nirenberg had ordered churches closed before Gov. Greg Abbot reversed the decision. “If we want to keep people alive, we’ve got to do services remotely,” Nirenberg told ProPublica and the Texas Tribune. “We’re entering a very dangerous phase of community spread.”

As Southern governors hemmed and hawed on stronger restrictions in recent weeks, public health experts looked on in dismay. States like Washington and California, which instituted strict restrictions on movement and business early on, appear to have “flattened the curve” much quicker than places like New York, potentially saving many lives in the process.

“These folks are being reckless,” Rebekah Gee, the former health secretary for Democratic Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards, said of governors who dawdled. “They’re going to cause worse financial problems for themselves. And other states, because we don’t have walls between states.”

New York City’s outbreak has garnered more headlines, but the per capita toll has been equally or more devastating in the South. Twelve of the 25 counties with the highest death rates in the nation through April 6 were in Georgia and Louisiana, according to an analysis by the Times-Picayune | New Orleans Advocate.

Louisiana was the first state in the Deep South to roll out a stay-at-home order, after an early outbreak in New Orleans, and there have been some signs that social distancing may finally be reducing the infection growth rate there. But Louisiana’s stringent order still came after the virus spread undetected for weeks in February, and the state’s outbreak has claimed a huge toll. More than 16,000 people have tested positive and more than 600 have died.

Gee and others say the high death rates are almost certainly due to the poor health endemic in the South before the coronavirus arrived. In Louisiana, 66 percent of coronavirus victims already suffered from hypertension, 44 percent had diabetes, 25 percent had chronic kidney disease, and 25 percent were obese, according to the state Department of Health.

As the coronavirus spreads across the South, it will strike states that never expanded Medicaid for poor residents and have seen small rural hospitals shuttered as a result. Gee worries that uninsured patients will crowd into emergency rooms that could become vectors of disease.

“We have lost time over the last several years, much less last several weeks. We failed to expand health care here in Mississippi,” said Shelton, the Tupelo mayor. “It all is cumulative. It all adds up. It all leads where we are right now.”

Covid-19 is already taking a disproportionate toll on African Americans. Black people make up 32 percent of Louisiana’s population but 70 percent of its deaths. An outbreak would be devastating in a place like Georgiana, an aging, predominantly African American town of 1,700 people in Alabama’s Black Belt. Its sole hospital closed last year after the state failed to expand Medicaid.

Mayor Jerome Antone said he was frustrated that Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey didn’t act earlier and more decisively to keep people home. At about the same time that she issued a stay-at-home order on April 3, he went further and imposed a curfew.

Decades ago, before he became a high school football coach and then a mayor, Antone worked for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracking down the spread of sexually transmitted diseases. And, like Shelton, his wife is a nurse. But he says he didn’t need special experience to realize drastic measures were necessary.

“It’s just common sense. I don’t want no blood on my hands,” he said.

Matt Sledge | Radio Free (2020-04-09T10:00:33+00:00) Southern Mayors Pushed GOP Governors to Take Action on Coronavirus. Governors Pushed Back.. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2020/04/09/southern-mayors-pushed-gop-governors-to-take-action-on-coronavirus-governors-pushed-back/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.