Nameless things would be similar

The steppe is endless but the horizon offers a way out. The steppe-beetles appear as from nowhere and surround us in their hundreds of thousands, climbing our legs, biting with pincers, their millions of tiny legs stamping the ground with an unbearable roar. And here are my parents and siblings, my children and wife, extended family, friends, people I have known and forgotten, indeed everyone I have ever known, many of them long dead, all of them attempting to brush the assailants off their clothes and skin, running now as fast as they can through the crawling swarm. I turn, see my father fall, and by the time I reach him he is already buried, his eyes and mouth full, then my mother goes over, and many around me fall, and the steppe reaches as far as I can see. I did what I could and ran for the border where relief would surely be at hand. But there is no border, and I have failed to help.

Doctrine of the Similar

Talat (not his real name) will soon be repatriated to Syria. He will return to his family in Aleppo, or what is left of them (family, Aleppo). Speaking of his time as a refugee, he remembers that when he felt lonely he would visit the family of one of his German classmates. “They were like my family”, he said. Did he mean, “They were like a family to me”? But perhaps he just meant what he said. They resembled his family in some way, or reminded him of them, or behaved towards him like his family used to? We might not ask.

The conundrum his statement posed, however, including the sentence Talat might have said but did not, were written all over his interrogator’s face. “Since they were absolutely not your family”, the interrogator asked, “in what way were they like your family?” But the focus of incomprehension had by this time shifted. For what kind of answer did Talat’s interrogator expect? Did he want to know if the German family corresponded in type or constitution to Talat’s own family: father, mother, brother, two sisters? Or did he think Talat meant that both sets of persons had arms, legs and heads? Or did the interrogator think he was he talking about their humanity, their kindness and warmth? Meanwhile, another question had formed in the interrogator’s mind: what is a family like? The problem is: for one entity to be similar to another, it also has to be different. But how do we know if we see likeness or difference? An emotion?

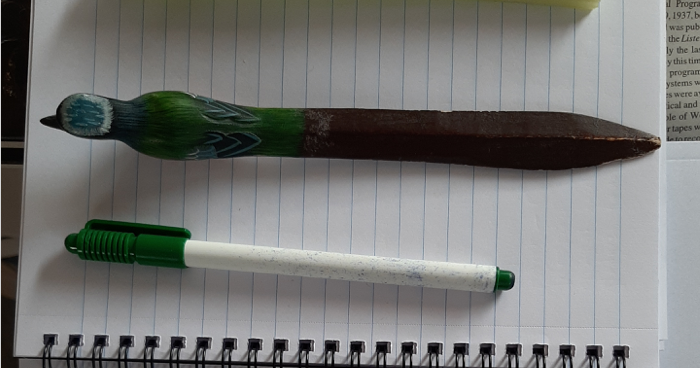

A celery stalk and a pen are similar, no? A tree-top and a plane? These become similar by our having to look upwards to see them. The poet might tell us that this is why two things can rhyme without sharing a phoneme. Similarities and rhymes may appear when we study the whole picture, or approach things from a certain angle. A word may rhyme with another word that appeared seven lines earlier, or with a word you think of when you read anther word. But what if we can’t see the whole picture, or the angle is wrong?

Similarity (or likeness) is constantly appearing and disappearing in relation to changing frames, times constraints and opportunities. There is no similarity per se. Cups of the same batch, identical design and colour, may, under certain circumstances, become as dissimilar as chalk and cheese, or the latter, if the frame category supports it, become remarkably similar. What similarity, as we speak, is coming into view or retreating from sight? In a crisis the similarity of things can be apparent for a split second then become imperceptible for the rest of time. Or we may recognize a similarity that has not been seen for three thousand years. Sometimes the world consists of likeness that we perceive unconsciously, invisible because it is always there. Do we always see two eyes staring back at us when we look at the word lOOk? Or is that only today? How difficult it is to read.

PrintIain Galbraith | Radio Free (2020-04-12T16:48:44+00:00) Family likeness. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2020/04/12/family-likeness/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.