By the late-90s we must have sensed that the shit was hitting the fan. The fire at Waco. The Unabomber envelopes. The downing of Flight 800. The World Trade Center bombing. Blowjobs in the White House. Oklahoma City. Tokyo’s subway sarin attack. The Khobar Towers bombing blamed on bin Laden. The ascent of Atlanta’s radio jockstrap Sean Hannity to national status on Roger Ailes’ newly established Fox News Network. OJ taking off the gloves. Rodney King wondering if we could all just get along. Cruise missiles on Bosnia on the eve of Clinton’s impeachment for blowjobs. Distracted from distraction by distraction, as T.S. Eliot famously put it, years before Karl Rove’s prosaic promise to fuck with reality-based thinking in the wake of 9/11.

As if America didn’t have enough problems, a foot soldier in the Army of God was afoot in the wee hours of July 27, 1996 at Centennial Park in Atlanta, where the Olympics were winding up for the night. Eric Rudolph, formerly of the Army of Exceptionalism — he’d been a special ops soldier in the Airborne 101 — was strolling near some benches behind the park, wearing a green backpack. There were dozens of people milling about. Rudolph sat on a bench and surreptitiously opened his backpack and set a timer on a huge bomb and placed the pack under the bench, then walked away hurriedly. No one saw him.

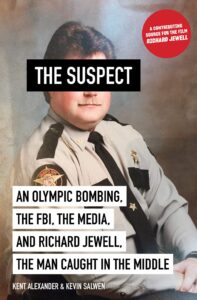

Rudolph rushed to a phone bank outside a Days Inn a couple of blocks away from the park and called in the bomb threat to 911. He used a plastic device to disguise his voice, and then, according to Kent Alexander’s account in the recently released book, The Suspect, the following took place: Rudolph said, “‘We defy the order of the militia …’ Click. The line went dead. The 911 operator had disconnected him.” Disconcerted at not being taken seriously, Rudolph called back, disguising his voice by pinching his nose, and said: “‘There is a bomb in Centennial Park. You have thirty minutes.’ He hung up. The call lasted thirteen seconds.” Confusion followed, with the 911 operator unable to find the Olympic Park address. Transcripts show insufficient urgency followed:

Rudolph rushed to a phone bank outside a Days Inn a couple of blocks away from the park and called in the bomb threat to 911. He used a plastic device to disguise his voice, and then, according to Kent Alexander’s account in the recently released book, The Suspect, the following took place: Rudolph said, “‘We defy the order of the militia …’ Click. The line went dead. The 911 operator had disconnected him.” Disconcerted at not being taken seriously, Rudolph called back, disguising his voice by pinching his nose, and said: “‘There is a bomb in Centennial Park. You have thirty minutes.’ He hung up. The call lasted thirteen seconds.” Confusion followed, with the 911 operator unable to find the Olympic Park address. Transcripts show insufficient urgency followed:

Dispatcher: Zone 5.

911 Operator: You know the address to Centennial Park?

Dispatcher: Girl, don’t ask me to lie to you.

911 Operator: I tried to call ACC, but ain’t nobody answering the phone … but I just got this man called talking about there’s a bomb set to go off in thirty minutes in Centennial Park.

Dispatcher: Oh Lord, child. Uh, OK, wait a minute. Centennial Park, you put it in and it won’t go in?

911 Operator: No, unless I’m spelling Centennial wrong. How are we spelling Centennial?

Dispatcher: C-E-N-T-E-N-N-I—how do you spell Centennial?

911 Operator: I’m spelling it right, it ain’t taking.

Valuable time expired, and the bomb squad, when they were finally called to the scene, had insufficient time to properly clear the area before the bomb went off.

At the start of Clint Eastwood’s latest film, Richard Jewell, the title character is followed by the director as he makes his rounds as an AT&T security guard outside a busy Centennial Park. Goofy and overstuffed, he is immediately seen as an oddball. Offering water to a pregnant woman in such a way that, though thanking him for it, she eyeballs him suspiciously. He confronts a group of drinking teens who diss him. On his way to get help, he sees the bomb under the bench. He asks passersby if the pack belongs to them. Alarmed, he alerts the assigned police crew, urging them to take action immediately, seemingly certain the pack is loaded. Bystanders are pushed to safety by Jewell, and others, when the bomb booms.

Paul Walter Hauser plays the complex character of Jewell, who’s not as dumb as he looks (or sometimes acts), and who gets caught up in a media frenzy that is fuelled by the wild speculation of a misinformed newspaper reporter, played by Olivia Wilde, and the entrapping tactics of the FBI — John Hamm playing the principle scofflaw fed. As the world comes at Jewell like a viral contagion, annihilating his privacy and reputation, he is buoyed up by his mother, played by Kathy Bates (in an Oscar-nominated supporting role) and Sam Rockwell as Watson Bryant, his lawyer and friend.

There’s been considerable controversy over the film’s depiction of the newspaper reporter from the Atlanta Journal-Constitution (AJC), Kathy Scruggs, played by Olivia Wilde. Eastwood has taken heat for her depiction, but he didn’t write the screenplay. The script is based upon Marie Brenner’s Vanity Fair article, “American Nightmare: The Ballad of Richard Jewell,” and The Suspect, Alexander and Selwen’s account of the bombing and its aftermath — including police investigations and news reporting. Only the latter sets up the scene where Scruggs allegedly received the confirmation from police that Richard Jewell was the primary suspect.

In The Suspect, Scruggs meets up with her source (unrevealed) at a bar — “someone she had known over the years. The source was about as plugged in as it got. She got down to business.” She was seated across from her source, and there was no hanky-panky:

The meeting was strictly off the record—that was understood. They ordered drinks, made small talk. After a few minutes, Scruggs asked the question. Are there any new suspects? Yes, the reply came back. One. “It’s Richard Jewell.” Scruggs’s heart pounded. Bingo. Jewell, the hero. Until now.”

To this day, this source is unknown, although Alexander and Selwen drop a couple of insinuating names in a couple of places.

Compare the Suspect scene above with the screenplay version (45-6) written by Billy Ray. In Ray’s account, Scruggs comes across as an eager beaver, who’ll do anything to get the scoop. Here’s how she’s depicted in the film:

Kathy:

I wouldn’t run it unless I had independent corroboration from a second source. That would put us in a different zone, as you know. (her hand drifting) Tom. You’re about to burst.

She leans in — that open blouse. He’s hard as an anvil.

Shaw:

First time in my life I ever wished I was gay.

Kathy smiles… then Shaw gives it up:

Shaw:

The Bureau’s looking at the security guard. Jewell.

WHOA. Kathy freezes. Did I hear that wrong? Nope. Trying to calm herself, she takes out her notepad.

The scene’s sexual banter is significantly longer in the film. There’s no question that it makes Scruggs look sleazy. But it’s also a condensed, slightly spiced up sum of all parts which Alexander and Selwel suggest throughout The Suspect. Is it Eastwood’s role to change a script for fairness to perceived reality? While Richard Jewell is based on actual events, Eastwood never pretends that his movie is “journalistic,” the way Katherine Bigelow did for Zero Dark Thirty. Did Scruggs sleep with cops to get information? The film says Yes, and The Suspect says Maybe (with a wink).

But Marie Brenner, in her Vanity Fair piece, “American Nightmare: The Ballad of Richard Jewell,” draws attention to a far more damaging assault on Scruggs’ reputation — the question of attribution in her story on Jewell and her reliance on ‘Voice of God’ journalism. Her lede reads:

The security guard who first alerted police to the pipe bomb that exploded in Centennial Olympic Park is the focus of the federal investigation into the incident that resulted in two deaths and injured more than 100.

Well, says who? Further defamatory sentences follow (here is the article) — without any attribution at all. It’s the Voice of God at work. Ironically, VOG was AJC’s rule: they’d “essentially banned” the expression “sources said” because readers might believe a quote was “fabricated.”

Brenner opens up the possibility that there was no source, per se, at all. And this line is taken further by Alexander and Selwen when they allude to the 1984 LA Olympics Turkish Bus bomb — planted by the ‘heroic’ officer who found the bomb. It may be, The Suspect suggests, that Scruggs had been given the hero-bomb anecdote and ran with it, in her passion to be the one who broke the story. Alexander and Selwen cite previous admonishments: “She was so eager to run with what trusted sources disclosed to her that editors often had to slow her down until she got more corroborating details.” Maybe there was no secondary corroboration.

The worst thing of all is that Jewell didn’t find out that he was a suspect until the AJC piece broke and went wild across the local and national airwaves. Overnight he went from a profile in courage to the profile of a loser — and, if he was imitating the LA ‘bomb hero, not particularly original either. None of it makes Scruggs look good as a reporter. But the AJC, believes the film has gone too far in portraying her as a quid pro quo “floozy,” and in “The Ballad of Kathy Scruggs,” Jennifer Brett complains that the harsh appraisal of Scruggs’ journalism is not balanced. She cites Scruggs’s brother, Lewis, who recalls, “… She was proud the FBI called her about Jewell. She was proud of the way she reported it to begin with.” But she shouldn’t have been proud.

The FBI did a disgraceful job handling the bombing, starting with director Louis Freeh, who micromanaged the investigation, and may have pushed the notion that Jewell be regarded as the prime suspect to his underlings in Atlanta — suspicions drawn from false profiling. It continued with the leak to Scruggs. But the most despicable thing they did was their attempt to entrap Jewell in a fake interview during which they hoped to extract information that ‘only the bomber could know.’ Jewell caught on, called a lawyer, and sought solace and protection behind his forceful and articulate mother, Bobi (played by Kathy Bates). Eventually the FBI conducted an internal investigation of their handling of Jewell, although the FBI later admitted, “We never went after the leak.”

Ultimately, it may be that it was FBI director Louis Freeh’s actions that were under-scrutinized in the half-assed investigation that followed. In The Suspect, Alexander and Selwen make clear that Freeh was calling the shots from Washington, and that he may have pushed the ‘bomb hero’ scenario on the Behavioral Science Unit (BSU) of the agency, forcing them to push out a false profile — without independently gathered evidence. Scruggs used their “lone bomber” profile, even though she should have known that Jewell couldn’t have been at the scene and making phone calls up the road — at the same time. He would have needed an accomplice, negating the “lone bomber” theory.

Richard Jewell might have perished emotionally or even have ended up imprisoned for the bombing, if not for his mother’s courage and ability to sway the media, as well as Watson Bryant, his lawyer, who is there when Jewell needs him, yanking back the naive and over-talkative suspect from FBI entrapment. Everyone seemed to be coming at him in his 88 day ordeal, before he was cleared. Not only was there the usual swarming rush to judgement, stoked by the sensationalist media, but he was viciously turned on, suddenly going from hero to goat. NBC Late Show host Jay Leno, was particularly horrid, referring to Jewell as “Una-doofus,” while he was a suspect, and calling him later, after he was cleared, “white trash.”

In the end, as we all know now, Eric Rudolph was arrested almost seven years later, for bombing a gay bar and two abortion clinics. In a plea bargain deal, he also copped to the Olympic Park bombing. Rudolph, an ex 101st Airborne special ops soldier, was a survivalist who went on the lam for five years after the Centennial bombing. He claimed that he was motivated in his bombings by hatred of gays, abortion, and general government over-reach. He fit the profile of a “lone bomber”.

Back in Jennifer Brett’s recent AJC piece, “The Ballad of Kathy Scruggs,” which seeks to correct the image presented of the reporter in the Clint Eastwood film, a friend, Tony Kiss, defends Scruggs, “She was never at peace or at rest with this story. It haunted her until her last breath,” Kiss said. “It crushed her like a junebug on the sidewalk.”

It’s ironic that both Jewell and Scruggs had a thing for cops — and in both cases they were let down, at great cost to their lives and reputations. The event produced a convergence of ill-will and evil rarely seen: media manipulations, police corruption, political and social reactionaries, insensitive Late Show jokes, a Christian terrorist who likes to blow people to Kingdom Come, frenzy and sensationalism.

Neither ever recovered. Jewell died aged 44; Scruggs died at 43.

PrintJohn Hawkins | Radio Free (2020-07-24T14:16:55+00:00) 88 Days of Hell for the Family Jewell. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2020/07/24/88-days-of-hell-for-the-family-jewell/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.