If there is one lesson all of us should have learnt during the Covid-19 crisis, it is about how to separate the ‘essential’ from the ‘non-essential’. In the different stages of the ‘lockdowns’ endured by much of the world’s population, we have stepped out to procure (or been delivered at home) only what is ‘essential’ for daily living, foregoing a lot that we may have in pre-COVID times obtained. We are talking here, of course, of those of us who have the privilege of living beyond survival, not about hundreds of millions of economically and socially marginalised people who have even in pre-COVID times been living on the margins.

What does this teach us about possible consumption patterns in post-COVID times? Let’s remember that COVID has come at a time when we are already in the midst of multiple other global crises, including runaway climate change, the first great human-induced biological extinction, irreversible pollution of air, water, soil, and our bodies, rampant human rights violations, growing income inequality, erosion of democratic space, and illnesses of both deprivation and affluence. Post-COVID, we have to get back to dealing with these multiple crisis, which may also assist us in avoiding further COVID-like situations. This requires fundamental changes in how we relate to each other as humans; and to the rest of nature, recalling here that many COVID-like outbreaks in the recent past have their origin in the massive destruction of natural ecosystems and in forms of animal use, including the industrial production of meat for global trade.

Unsustainable and inequitable production processes and lifestyles across the world are linked to unbridled affluence. Such processes and lifestyles require the destruction of forests, the mining of lands, the damming of rivers, the conversion of enormous areas into industrial meat or monocultural crop production. Apart from irreversible ecological damage, they lead to the displacement of millions of people from their homes and lands.

The vast majority of ‘goods’ produced for affluent lifestyles are ‘non-essentials’ that are not needed to live well. They are the result of the availability and the affordability of an artificial abundance, created by runaway globalisation of finance and trade, the expansionist logic inherent in capitalism (in whose logic is also the ‘metabolic rift’ between humans and nature, that Marx spoke about), aided by pliant states. But what the ‘affluent’ class demands is available only in finite quantities; we are fast running out of the materials our products are made of or the ecosystems they are embedded in. Each time we discard a mobile phone that is still perfectly usable, to buy the latest model, we contribute to devastating mining in the Congo or some other place on the planet. Every time we take a flight to holiday in some ‘exotic’ location, we add to the climate crisis. A vast number of the things we consume are based on fossil fuels, either directly like plastics, or indirectly as in their transportation or in the energy used to produce them. The ecological and social footprint of people who can buy products and services from anywhere in the world, goes well beyond what we can even perceive.

Consumerism of world’s rich is virtually unregulated | Image: Ashish Kothari

Consumerism of world’s rich is virtually unregulated | Image: Ashish KothariChanging this requires fundamentally altering the way our economy runs, and who runs it; currently dominant neo-liberal ideology and practice, dictated by the powerful financial-military-industrial complex, promotes greed-based accumulation rather than need-based consumption. It justifies ever-increasing possession of goods, or consumerism, in the name of ‘development’ and ‘growth’. It hides the fact that such growth has no necessary connection to eradicating poverty and deprivation, and in fact may enhance it by undermining nature-based livelihoods and increasing inequality. In fact, what we need is an urgent discussion on, and moving to daily practice, what is really essential to be a human being, rather than a human wanting.

This is not an easy distinction to make. There are some products that perhaps most people would easily categorise into non-essentials (and some would classify as regressive): Formula 1 racing, golf courses, luxury cars and yachts, private jets, the fashion industry, the colossal beauty products industry. But there are others that were luxury at one point, then came to be considered necessities: electricity, refrigerators, washing machines, microwave ovens, cellphones, personal motorised vehicles. How can one make a distinction that is not purely arbitrary? Can we have moral and ethical guideposts for making this distinction, and/or criteria like what impacts their consumption has?

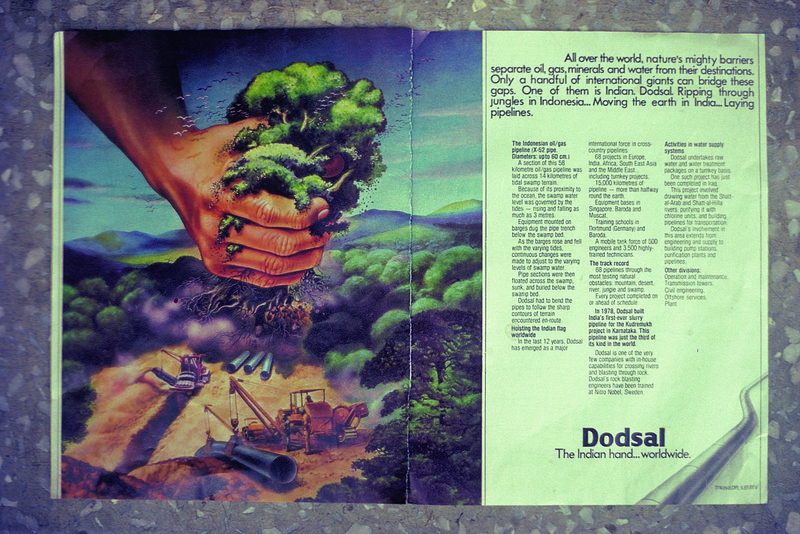

Development as corporations see it | Image: Ashish Kothari

Development as corporations see it | Image: Ashish KothariThe ancient Indian concept of aparigraha, central to Jainism, teaches us the value of self-restraint, or non-possession. Sages and wise people through history have preached the importance of simplicity, or simple living, and appreciating that, as E.F. Shumacher put it, ‘small is beautiful’. But moral principles are often resisted by us, especially if someone tries to ram it down our throats. Perhaps these can be complemented by ethically based pragmatic insights, such as Mahatma Gandhi’s Talisman that whatever step we take, lets ask ourselves whether it will benefit the last person (and we can extend this to include the last species), combined with his pithy insight that the earth can support everyone’s need, but not everyone’s greed. Or the worldview of several native peoples of Turtle Island (the indigenous name for North America), who believe that every step they take must take into account impacts on the next seven generations. Living in co-existence, peace and love are at the heart of most ancient faiths and belief systems.

But can the earth even support everyone’s needs? This depends on us re-learning what is essential or what comprises basic needs. Clearly, adequate and appropriate amounts and quality of food, water, housing, clothing, energy, and the opportunities for good health, are everyone’s right. But so are many of the non-material elements of life: social relations, relating to the rest of nature, access to spaces for learning and spiritual growth, having a collective to learn from and contribute to, being guaranteed a voice and a say in collective decision-making, and ensuring a gender perspective in all of the above. In fact, the COVID crisis has brought these sharply into our consciousness, especially where people have faced hardships and been helped by acts of solidarity, where people have suddenly experienced clean air, where people have been forced to or been given a chance to re-connect with family and ‘pets’ and neighbours in lockdown conditions, or even just reflect about themselves and the meaning of their work and lives.

Dongria Kondh indigenous people, eastern India – showing how simple life within nature can be fulfiling | Image: Ashish Kothari

Dongria Kondh indigenous people, eastern India – showing how simple life within nature can be fulfiling | Image: Ashish KothariThis immediately also brings up the sharp reality of half of humanity not having even their basic needs being met. Billions of people have been denied both their material and non-material needs, as economic inequality has skyrocketed abysmally in the last few decades, growth-centred notions of ‘development’ have snatched away survival resources like land and water, neo-liberalism has privatised and commodified basic human rights like health, education and housing, and right-wing governance has reduced democratic spaces. All this builds on older inequities of casteism, racism, patriarchy, and the like. Tackling global crises has to squarely deal with such inequality and deprivation, which also means that predominantly technological or market-driven fixes are simply not going to cut it. There is already enough wealth and production; instead of further growth, into which unfortunately even the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG’s) are embedded, we need a radical redistribution of power and wealth from those in whom it is concentrated to whose who have little or none.

Many of Mahatma Gandhi’s concepts are crucially relevant: sarvodaya, the uplifting of all, the consciousness that we live in one world; swaraj, where individual and collective freedoms are based on responsibility towards everyone else’s freedom; and satyagraha, speaking truth to power and the right to protest peacefully. We need to move towards a world where economic systems work on the basis of the ‘welfare of all’ and uphold the ‘right of all’ beginning with the most marginalised. If the search is for satya (truth), the primary force that should guides us, then economics has to involve itself in the search for truth and social justice. Notions like the ones above or of classlessness stemming from Marx, not to forget innumerable indigenous or peasant visionaries including those in ongoing movements of the Zapatistas and the Kurdish women, have to become the driving force of economics rather than the search for growth based on consumption, capital and profit-seeking. And the same goes for politics, moving from concentration of power in the hands of a few ruling over the rest, to a comprehensive redistribution amongst all people, towards a radical democracy.

Handmaking cloth (taking back control over basic needs), Common Ground Fair Unity (Maine), Sept 2008 | Image: Ashish Kothari

Handmaking cloth (taking back control over basic needs), Common Ground Fair Unity (Maine), Sept 2008 | Image: Ashish KothariCOVID has considerably inconvenienced most of us. But this brings up the issue of what is ‘convenience’. The growing individualism and selfishness of westernised modernity has made us think of any kind of physical labour or effort as ‘inconvenient’. This enables corporations to feed the privileged ‘convenience’ and ‘comfort’, outsourcing physical work to machines or to cheap labour. It has made us inconsiderate to the fact that someone somewhere is paying the cost of our convenience, whether because of the enormous ecological cost (home-based electrical appliances are a major source of emissions, as are chemicals in agriculture that make operations faster or ‘easier’), or because others are deprived of dignity or of their survival resources. We live in a unique age when we will use our cars to drive half a km to the mall, and then spend money going to a fitness class!

Income and wealth inequality have also to be tackled in other ways. Substantially increased taxation on the rich has been recommended ad infinitum, but rarely have states plucked up the courage to impose this. Possibly no country has an upper limit on salaries or earnings through financial markets, which in corporate circles (and even some NGOs) have reached astronomical proportions (and in fact jumped in the COVID period, especially for online retailers like Amazon). Radical redistribution of wealth will in fact achieve much more than increasing economic growth rates, and will do so without adding to the ecological devastation that market-based growth entails.

Accompanying all this, of course, also re-embedding ourselves within nature as one amongst innumerable life forms, respecting that the earth was made for all species, not only humans. Gandhi’s notion of trusteeship, beyond its role in the relations within humans, is also complementary to the indigenous worldview of custodianship, in which we are not owners of nature, but rather its part, and have been bestowed the responsibility of treating it as heritage for future generations.

Crucial to all of the above are significant cultural and mental shifts. Capitalism and competitive modernity, with patriarchy or masculinity as a base, thrive on selfishness and individualism, driving the trend towards privatisation of every sector of life – in fact, of life itself, as we see in the patenting of plant and animal species. Struggles to re-common public spaces and goods – including water, air, land, forests and other ecosystems, and even information/knowledge, software, art and cultural heritage – are crucial for the reconceptualization of society that works for all. The cultural and mental shift also requires an understanding of another point that Gandhi made: rights cannot be assumed without corresponding duties and responsibilities. This remarkable insight also made it into the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 29). In the context of climate change this becomes a powerful point that can guide our actions as individuals, collectives, institutions and nations.

Finally, the colossal livelihood crisis in many countries due to COVID (and the attendant lockdowns and dramatic drop of economic activity), along with other ongoing global crises, compels us to rethink the logic of rapid urbanisation, often pushed as deliberate state policy, as in China and India. Surely the need now is to de-urbanise by taking whatever steps are necessary to ensure self-reliant, sustainable, socially just rural livelihoods, based on rights over housing and land and responsibility towards conserving nature? This alone will ensure a secure future for the hundreds of millions who to continue to depend on rural economies. Such economies can diversify to complement renewed farming, pastoralism, fisheries, forestry, and crafts – livelihoods in the traditional sectors – with manufacturing and services, including community-led hospitality, to enable full livelihood security. This will also ensure that the pressure to live insecure and uncertain lives in inhospitable urban areas is not a choice forced on migrants.

Sapara nation members in Ecuadorian Amazon – ‘modern’ society needs to learn living with the earth from indigenous peoples | Image: Ashish Kothari

Sapara nation members in Ecuadorian Amazon – ‘modern’ society needs to learn living with the earth from indigenous peoples | Image: Ashish KothariBut equally, where such people still choose to move to or continue living in cities, movements to ensure rights to dignified, safe working and living environments, and significantly higher remuneration than they receive now, are important. There are thousands of initiatives already achieving this across the world, from which we must learn, and for whom supportive policies have to be advocated, to be able to spread them widely. They are (or can be) embedded in a pluriverse of worldviews and concepts of well-being that are emerging or being re-asserted as part of justice movements: swaraj, buen vivir, sumac kawsay, ubuntu, sentipensar, ecofeminism, conviviality, commons, degrowth, and many others.

The measures described above also encompass a growing desire to once again do things with the hand (‘the future is handmade’), including in the most mechanised and industrialised societies of Europe and North America, or in the soul-deadening IT industry, and even amongst the youth. The main challenge here is, how this is not restricted to an elite pastime (rich young people going into organic farming), but is something that recognises and respects the skills and knowledge of people who have been traditionally working with the hand, enabling self-esteem in such work to return, and with the currently privileged going into it with humility and the desire to learn from such people. Transforming the education system to include craftspersons, farmers, and others as teachers, providing opportunities for children and youth to engage not only with their mind but also their hands and hearts (Gandhi’s Nai Taleem approach), may produce new generations that can find enjoyment in the simple pleasures or life, rather than in the mindless pursuit of luxury and non-essential wealth.

PrintAshish Kothari Miloon Kothari | Radio Free (2020-08-10T09:16:35+00:00) We are doomed if, in the post-Covid 19 world, we cannot abandon non-essentials. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2020/08/10/we-are-doomed-if-in-the-post-covid-19-world-we-cannot-abandon-non-essentials/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.