Visual artist Moshtari Hilal discusses being visible on Instagram, learning how much to charge for your work, and seeing other people copy your aesthetic.

You often wear the pakol, which is the tribal Afghan wool hat atypical for women to don. What’s your relationship with Afghan clothing and how does that reflect in your work?

To be honest, I really don’t like how women dress in Afghanistan. I have the feeling that they have to hide and wear heavy or really cheap things made with bad quality, not even cotton. At the same time, I liked how men dressed. They dress in the colors of the country, like the blue sky and the color of the mountains and of the sand. The stone colors. I liked the colors, and then also the styling of perahan tunban and everything they wear was so close to the minimalism I use for my Western or even Japanese-influenced clothing. So I always liked that.

I also didn’t understand why there is no gender crossdressing in the Afghan context—like why shouldn’t we be able to just appropriate men’s clothes if they fit us? Even when we go to Afghanistan, my brother would get dast doozee [handsewn fittings] for his perahan tunban. I would take them, because I never got them, and make fits for my body so I could also wear them and walk around in these outfits.

A lot of your work is on Instagram, and you have a large following. Did you intend for it to be a space for people to find your work when you first started? How did that evolve?

I guess I was really conscious about Instagram. I actually planned to build a platform for myself on Instagram since I didn’t study art, and was not really involved in the arts. I had to find my own place—I didn’t have a gallery or university professor who would see my work and then mentor me. I just started with Tumblr and then I had Facebook. I even did a YouTube thing in the really early stages when I was really young. So I always tried to find the best platform, and in the end, Instagram was the best platform because it was so reduced to the visual experience. I got really involved with people who did the same—artists of color, especially based in Berlin, who try to challenge the same things or work in the same independent way as me. We just met up and talked and it grew from there.

I didn’t know that you also had a YouTube, is that still up?

No, I deleted it. It was so embarrassing. It was just for experiments.

What kinds of videos were you doing?

It talked about things I bought and why I bought them. But at the same time, I didn’t even have money, so I would actually tell them what my mother bought me. I was really young.

But that’s the cool thing about the internet. You can try everything out and you don’t have to be in any broader context or project or institution. You can actually just log in and try it. I love that. You can apply for something, go to classes or actually find the right institution to meet people. But you can also sit at home, log in, teach yourself, try something out and then upload it. It’s a shorter way, so it can also be really stupid. You can upload a lot of bullshit. The good part is that you don’t have to ask anyone, no one has to agree with you, and you can still just use a platform. There is no authority.

You’ve done a lot of commission work for people, like Wes Anderson’s set decorator, who misidentified you as Indian. When a commissioner reaches out to you, how do you make sure you’re properly compensated and navigate the tricky conversations that might come out of that?

I think this is something I’m still learning, because especially when you start, you’re really at the beginning of what you do. You’re so grateful for every opportunity that sometimes you undervalue yourself and just take exposure instead of an actual check. This is something you have to learn and find out: This industry is doing research on new artists or edgy, subversive social media artists because they can pay them less and can also be like, “Look, we discovered this person. Look how we found this person, we worked with this person.” But they will not pay them as much, or at all.

This is something you have to learn, and I am right now in the process of actually saying “no” to some things that reach me. Sometimes I’m like, “I can’t send you artworks if you don’t give me a contract or insurance or anything, and if I have to pay for the transport myself.” I mean, why should I do that? Because if a project has enough money to do PR or print something or pay for random things like catering, they can also pay an artist at least a little bit.

The problem is if you’re self-taught and you’re suddenly interesting to the market, nobody told you how to behave in the market since we don’t talk about money as a society—which is stupid because money controls everything. It’s so hard to compare yourself and know what you should charge for the work you do.

When I draw or do an artwork, I don’t think in terms of money. I still have problems telling someone how much an artwork costs, or how much I want for an artwork if they want to buy it. Because for me, the worth is way more than what I actually would sell it for because I put so much love and time into it. It’s hard to be so personally involved and passionate about your art and then commercialize it. I think this is a rationalization that you have to learn, and it’s not natural and it’s not organic.

Do you ever have conversations with fellow artists on social media about this?

I’ve had moments when someone else told me, “Yeah, you should charge this,” or, “You should ask for more,” and they helped me have the confidence to ask for more. But also I did some internships where I was organizing these sorts of things. I know that when someone gets an email, the actual budget is way higher than what they tell the artist it is. So everybody can ask at least once for more. If they really don’t have anything, you can think about whether or not you still want to do it. But asking for more and having the confidence is something I learned through other people who did it before me.

How do you feel about people sharing your work online? There’s a weird thing where individuals and brands will share artwork without attribution or compensation.

I mean, on the one hand, sharing and exposure is the whole idea of Instagram, so if someone shares your picture, that’s the point. Why post it if you don’t want it to be in the public and shared? But sometimes, when there’s no credit or if someone is sharing it in a commercial context, it’s weird because other people might get paid for that. Since social media platforms are now also commercial places where people can actually buy a post, I think big companies should also treat smaller artists as they would bigger artists and actually buy the right to share their work. But sometimes that’s also complicated, because there’s private content mixed with public art content on many profiles, such as mine. I try to reduce that now, because sometimes people think they can also share your private content, which I feel really weird about. Once I posted a picture of my father in my Insta story and someone posted it on his story. I was like, “Um, this is my father. Why would you share that?”

That’s so weird.

The person was like, “Yeah, I’m sorry, I thought it was so beautiful.” I’m like, “Yeah, but please delete it.” So the person deleted it and it was okay. But sometimes people think you’re a public figure and everything you do is public property, but it’s not. It’s not public property. But in a way, it is. This is the problem. When you log into a social media platform like Instagram you actually give the rights of your picture and your images to Instagram. You have to think about that. It’s so strange. I don’t know what I think about it.

I don’t know what it’s called in English. In German it’s called Urheberrecht, which means the first person who actually had the idea also has the rights to the idea. If you write a book and someone is not quoting you, taking a sentence from your book and not quoting you, it’s against the cultural artistic property rights of the author. This is something we don’t have on the internet anymore. Sometimes I’m like, “Yeah, this is good because things should grow, and sometimes art is bigger than the artist.” But we live in a very commercial world and the artist has to make a living.

I remember a little bit ago you posted something on your Instagram story about artists who were maybe using your aesthetic and copying you.

Yeah, people would send me young artists’ images and be like, “I think this person’s copying you, and this person’s copying you, look, blah, blah, blah,” and I was like, yeah, I don’t know. I can see that they were deeply inspired by my work.

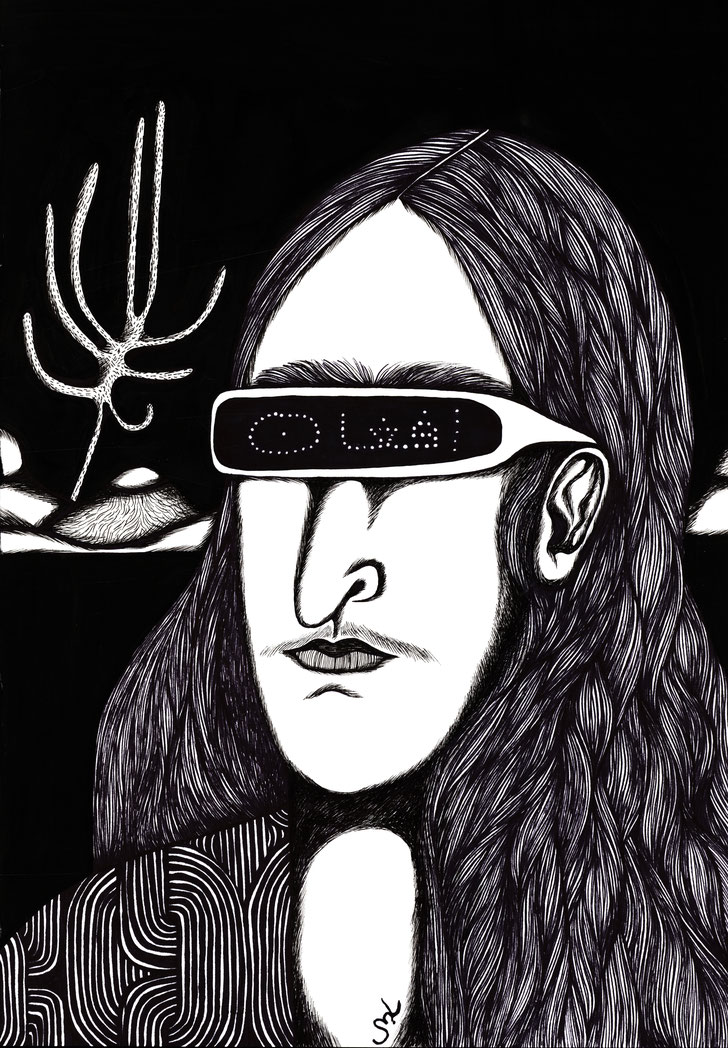

People send me pictures of artists drawing a big nose or a mustache or drawing in black and white and they’re like, “Oh, look, this is like your work,” and I’m like, it’s not. I mean, just because we both have a black-and-white aesthetic doesn’t make our work the same. There are so many artists drawing and working only in black and white.

But also, I have seen people inspired by the mustache, or embracing the face aesthetic of my portraits. I think it’s really good that they do that, because this is what I want. I want people to find beauty in these aesthetics. But at the same time, I don’t think they are really doing what I do because I think my work comes from a really personal exploration of myself and my surroundings. There is a specific mood or nostalgia in a lot of things I draw that you can’t copy. I don’t know how to explain it. It’s just a feeling I know. I can’t rationalize it right now.

You often say your work is semi-autobiographical, right? So it’s quite impossible for someone to try to do exactly what you’re doing.

Yeah. Also, I don’t know if you saw these messages I got from this Iranian guy who would message me, “Yeah, I followed your work because I like your artwork, but stop posting selfies.” I mean, my personal relationship to myself, to my own aesthetic and to my artwork, are so close they’re influencing each other. I can’t do one without the other. It’s so close, as you said, there’s so much autobiography in it, but there are also these moments where I’m thinking about something bigger because of my personal experience. There’s a genealogy which is always coming back to myself.

So it’s not a trend, you know? I know it’s a trend right now, it’s a trend to decolonize your beauty standards, beauty in all shapes and colors and diversity, blah blah. That’s a trend and it’s good that it is a trend. But even if the trend is over, it’s not over for me because for me it’s just existence and reality. For me it’s not political content. For me it’s just my content, and it’s timeless.

Do you ever feel weird posting pictures of yourself or using your image in that way?

Yeah, sometimes. I mean, I have these moments when I would actually go into my feed and delete what I think is too private or too personal or too close to myself and too far away from my artwork. But at the same time, I myself felt so inspired by people being visible as Ayqa Khan. I clearly can remember that moment when I saw her for the first time on Instagram. I had just watched Moonlight in the cinema and I saw things I had never seen.

I saw black bodies being queer and loving and so sensual. I had never seen that in that way, so I actually felt how my brain would absorb new information. I felt how my visual memory would completely reconfigure. That moment I had was also when I saw Ayqa Khan on social media, especially her photography and selfies. I thought, “Oh my god, there are people like me out there, being so visible.” She was just there as if it was her right to be visible.

These messages that I mostly get from men were questioning my right to be visible, because I didn’t fit their beauty standards. We assume the internet is a free space. It’s not—we have to fight for visibility and have to claim these spaces. These are political vocabularies, because being visible in such a world is really political. I think my selfies are probably not artwork, but maybe self-care for myself. I feel better if I’m not hiding. It’s also political because I know people use it as an inspirational source, seeing me in the same way that I see other people like you or Ayqa Khan being visible.

I am also obviously very inspired by you. To me, it’s symbiotic. We enable each other to feel comfortable and empowered. I definitely drew inspiration and felt empowered to post what I normally wouldn’t post, like showing my body hair, because of people like you.

Yeah, it’s a visual community.

That’s exactly what it is. What else is important to you right now?

I think what is important for me right now—what I am thinking about right now a lot—is how to develop a visual language or handicraft that comes from these conversations that we just had. This political value of looking at yourself and finding beauty in yourself and finding beauty in the aesthetics of black-haired bodies, and translating all these really pop-cultural, political approaches into something more abstract and into something even more timeless and less personal. Something that could be bigger than the personal experience.

How can I create this art that came from the self-portrait and the self-image and translate that into something bigger, such as a whole grammar, language, and vocabulary of an aesthetic that has a starting and an ending point that I could also use when making sculptures, paintings, and movies? Something that can be translated into any other form and you would recognize it. This is something I’m aiming for right now.

Moshtari Hilal recommends:

-

Jorja Smith: I like this one song that’s not even on the album, which I don’t understand, It’s called “Beautiful Little Fools.” You can watch it also with a video on YouTube. It’s really nice.

-

Sevdaliza: She’s an Iranian Dutch artist and she’s so good. Her aesthetic is so strong. She’s also self taught and started one year ago or something. She’s the new shooting star.

Rona Akbari | Radio Free (2020-10-20T07:00:00+00:00) Visual artist Moshtari Hilal on compensation and visibility. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2020/10/20/visual-artist-moshtari-hilal-on-compensation-and-visibility/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.