A long-running clash between Wall Street bondholders and the people of Puerto Rico is coming to a head, as the Trump administration looks to lock down gains that financiers have made in their battle with the island.

The fate of the island hinges on the terms of a bankruptcy-like deal currently being hashed out by a seven-person, unelected control board and a bankruptcy judge, all of which must be ultimately approved by the legislature and governor of Puerto Rico. President Donald Trump’s defeat in his reelection campaign and the forthcoming change in administration has triggered a jockeying for power inside the board, with Wall Street creditors targeting key positions — which Republicans recently scrambled to fill with appointees seen as friendly to bondholders.

Of particular concern to critics of a bondholder-friendly deal is Trump’s appointee, Justin Peterson, who is tied to a firm that represented the very same vulture funds that stand to profit off Puerto Rico’s debt.

The stakes for Puerto Rico’s future will be enormous, said Julio López Varona, co-director of community dignity campaigns at the Center For Popular Democracy, which spearheaded a letter laying out a list of demands for President-elect Joe Biden by more than 30 organizations from Puerto Rico and its diaspora.

“In the next 2 months an unelected fiscal control board will present a restructuring deal worth upwards of 30 billion dollars that will impact the people of Puerto Rico for decades,” López Varona said by text message. “The current deal provides payments to hedge funds and millionaire bondholders by cutting pensions and forcing Puerto Rico into a long haul of austerity-driven policies that will force even more people to leave the island and will threaten the stability of essential services. This happens while the island is in the middle of a pandemic.”

If the board strikes a deal that favors bondholders and leaves the island’s debt load at an unsustainably high level, it could set the commonwealth on a predictable course. Austerity and cuts to social services will be needed to pay Wall Street and could further hamper the economy, driving an exodus from the island and fueling a vicious cycle that would lead in fairly short order to a new bankruptcy. The end result could be that Puerto Rico’s assets are sold off and the island is turned into a full-blown playground for the mega-rich.

The alternative path, beating back the bondholders, could allow Puerto Rico to invest instead in its own future.

The fight also has political implications. As Puerto Ricans fled the island over the past several years, escaping the misery of Hurricane Maria and its economic fallout, Democrats hoped to cash in at the ballot box. But Puerto Ricans broadly dashed those hopes, voting in sizable numbers for Republicans. One driver of this dynamic was Puerto Ricans’ displeasure with the legislation that created the fiscal control board; it became a stand-in for Puerto Ricans’ anger at the rapacious treatment they’ve received. The bill was bipartisan but was signed into law by President Barack Obama in 2016 and has come to be associated with Democrats.

It’s all moving fast and, as usual, Puerto Rico is far from the minds of Washington’s power brokers, though people with the ear of Trump are circling. For instance, former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, a Trump confidante, has two lobbying contracts related to Puerto Rico and strong links with the financial interests eyeing a payday.

Photo: Victor J. Blue/Bloomberg/Getty Images

On the debt front, Puerto Rico’s Financial Oversight and Management Board, known locally as la junta, is required to submit a plan to Judge Laura Taylor Swain by February 10 for managing $35 billion in debt to bondholders. At stake is how much the government will cut into ordinary Puerto Ricans’ pensions and social services to pay them off. The deal on the table now would relieve about 66 percent of that debt, while cutting pensions by 8.5 percent for those who receive more than $1,500 per month.

Critics say the direction of the deal unfairly apportions much of the payback to hedge funds and that it’s unsustainable, leaving the island vulnerable to a future default. But with Republican appointees at the table — especially a pair of new appointments seen to be friendly to bondholders — many are worried that it could get even worse and that billions of additional dollars could be pushed back into the hands of predatory creditors.

Trump’s Pick

Puerto Rico’s debt exploded in the mid-aughts, driven by the sale of relatively high-risk, high-interest bonds, as federal policy changes decimated the island’s manufacturing base. As a default on the debt became more and more inevitable, vulture funds bought up the bonds at a steep discount, positioning themselves for huge returns if they could force the island to repay in full — a version of a plan such vulture funds carried out in Argentina.

The board trying to hash out the deal on the debt was created by a politically fraught law called the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act, known as PROMESA, set up to determine how much money the vulture funds will get.

The board’s seven seats are apportioned through a system where the majority of each house of Congress gets two seats, and the minority in each chamber gets one, plus one outright pick from the White House. When Trump became president, the GOP majority became 5 to 2, cementing the power of the bondholders. But when Democrats took back the House, it shrunk to a 4-3 Republican margin. With Biden to be sworn in, Democrats have the chance to win back control, but only if they can make a long-shot bid to force out Trump’s pick, who has already stirred up controversies in a few short months in his seat.

Justin Peterson came into the board at a moment when three seats remained vacant. All seven junta members’ terms expired in the summer of 2019, but Trump didn’t immediately move to fill them, even as members left. Trump only moved to fill his own seat in October, naming Peterson, a managing partner at DCI Group, to a three-year term. Peterson’s appointment in October ratcheted up tensions significantly, with Rep. Nydia Velazquez, D-N.Y., attacking him over his longtime role with the vulture funds.

A very Trumpian tweet from a Trump hack. I want to know, @JPHusker_ who are you making deals for?

The people of Puerto Rico or your buddies from your time as a lobbyist for the bondholders? https://t.co/P961asD0Am

— Rep. Nydia Velazquez (@NydiaVelazquez) October 23, 2020

“As of the summer of 2018, I have not worked for anybody who had bonds on this set of issues,” Peterson told The Intercept. “So, no conflicts and frankly I think that all the stakeholders involved need to do their own work. What I want to do is create a transparent and fair process.”

Publicly, Peterson has declared, “Puerto Rico should be governed by its elected leaders — not a permanent Board” — an echo of a point that anti-austerity opponents of the board have also made. Peterson’s history working with vulture funds that have designs on the island, however, has often put him at odds with those opponents.

DCI Group has worked for some of those same hedge funds that feasted on the crises in both Puerto Rico and Argentina. In turn, the firm has lobbied extensively on matters related to Puerto Rico’s debt and launched campaigns designed specifically to assure that the big Puerto Rico payday arrives.

On behalf of Doral Bank, which was seeking $229 million dollars from the commonwealth’s government, DCI launched what Puerto Rico’s largest paper dubbed a “smear campaign” against the Puerto Rican government in 2014. As part of the campaign, the American Future Fund, a dark-money group out of Iowa, published full-page ads in the Wall Street Journal and Politico, claiming a debt plan by former Puerto Rico Gov. Alejandro García Padilla would stiff seniors and retirees. For another group of bondholders, DCI paid Puerto Rican political figures to influence public opinion, according to El Nuevo Día. DCI also had a hand in a campaign by an astroturf group called Main Street Bondholders, according to reporting by the New York Times, cast as ordinary bond-holding retirees who stood to lose their life savings due to Puerto Rico’s fiscal irresponsibility.

Peterson himself, according to the Wall Street Journal, previously advised two particularly aggressive Puerto Rico bondholders, Aurelius Capital Management LP and Autonomy Capital. Aurelius, like Peterson, has positioned itself as an opponent of the fiscal control board, filing a lawsuit claiming the junta is illegitimate, since its members are not confirmed by the Senate. It was a bet that, without the board, the firm could squeeze something closer to full repayment on bonds it had bought for far less than their full value. The firm lost the case in the U.S. Supreme Court this summer. Peterson has said he has not worked with the companies since 2018.

As president, Biden could hypothetically remove a board member, but he would need cause — something Biden is unlikely to use Peterson’s previous hedge funds work for. Asked about that pressure, Peterson said he felt comfortable that he’d remain in his position. “I would refer you to statute,” he said. “I’ve stated the reasons why I want to do this and I want to work for the people of Puerto Rico, but this is a democracy and people will make their case.”

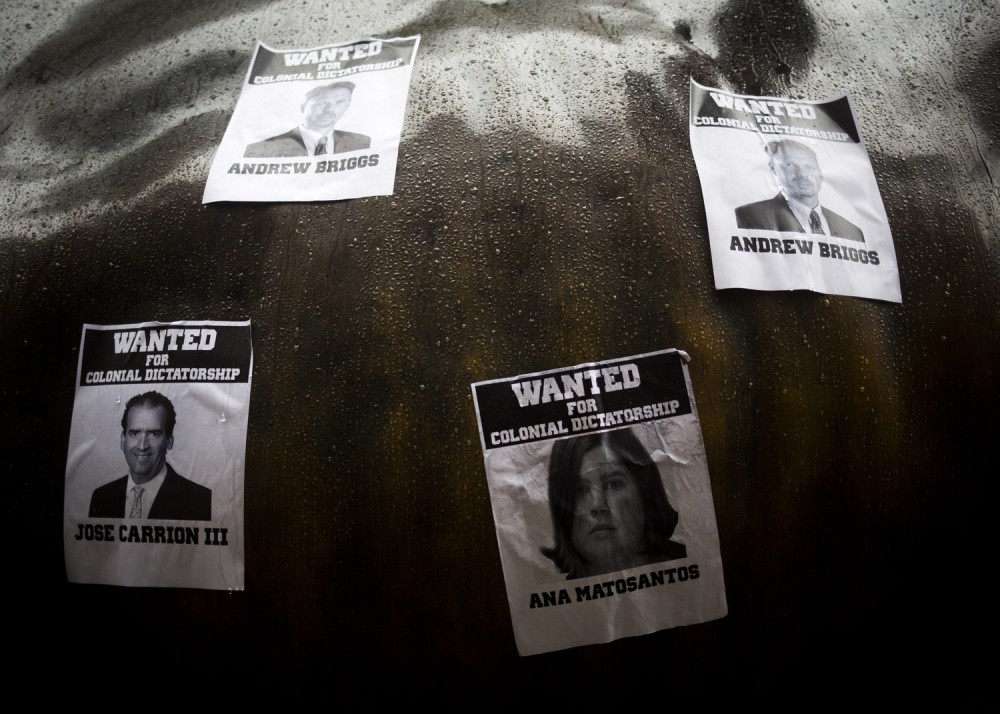

Left/Top: Mock “Wanted” posters featuring images of members of Puerto Rico’s fiscal control board members are seen on the Charging Bull sculpture during a demonstration in New York City on Sept. 30, 2016. Right/Bottom: Members of the activist group CANCEL THE DEBT blocked midtown intersections to protest MoMA board of trustees member Steven Tananbaum, the owner of a large amount of Puerto Rican debt through his hedge fund company GoldenTree, in New York City on Oct. 21, 2019.Photo: John Taggart/Bloomberg/Getty Image; Erik McGregor/LightRocket/Getty Images

Energy Industry Work

Peterson’s role on the board could also have an impact on energy and climate change policies — areas that he worked on at DCI Group.

Peterson’s profile on DCI’s website notes that he leads the firm’s energy practice; he “has two decades of experience advising senior executives in the oil and natural gas industry” and “has led efforts to roll back harmful regulations, expand oil and natural gas development, and defend the reputations of large energy companies under attack by activist groups.”

Under Peterson’s watch, DCI appears to have been an important player in Exxon Mobil’s effort to cover up its early knowledge of the climate crisis. The firm registered as a lobbyist for Exxon Mobil starting in 2005 until DCI was subpoenaed by the Virgin Islands in 2016 as part of the islands’ Exxon Mobil climate denial investigation, which was later dropped under pressure from the corporation.

Much of DCI’s work for the fossil fuel industry does not show up in public records, but where it has been unearthed, Peterson’s name appears frequently. DCI ran a website funded in part by Exxon that laundered climate change denial as carefully researched op-eds; Peterson is listed repeatedly as vice president in the records of a nonprofit apparently set up to fund the web publication. An invitation list, later leaked to Greenpeace, for a 2006 event hosted by DCI on the Clean Air Act included a who’s who of climate deniers — alongside Peterson and another DCI Group staff member. More recently, DCI has also engaged in controversial pushes in favor of oil pipelines.

Peterson’s experience with energy issues could come into play in his new role on the board, which is overseeing the privatization of the island’s power utility and has the power to fast-track so-called critical infrastructure projects. It’s a process that has been at odds with a law that says the island must move to 100 percent renewable energy by 2050 and with the island’s movement for community-led rooftop solar energy.

The power utility issue is one Chris Christie is engaged in lobbying on: One of his contracts is with the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority, or PREPA, which is amid a controversial privatization process.

“Everybody kind of focuses on the restructuring process, but there’s other important things going on,” said Peterson. “The LUMA deal is a big step forward for Puerto Rico. This is something that would move the transmission function from PREPA to this company LUMA and will create efficiencies and help with some of what Puerto Rico needs to do to become more competitive in terms of attracting business.”

Board Politics

Peterson has already shaken up the board. At the end of October, he dramatically stormed out of his first public meeting, derailing a vote on the filing of the debt restructuring plan and claiming that the deal should be negotiated with bondholders first. It put a stake in the ground on how Peterson is likely to proceed. “I think it was a bit of a show from Peterson, to show he has a different agenda,” said Sergio Marxuach, policy director and general counsel at the Center for a New Economy. Peterson, though, is not the only new board member that could shake things up.

On December 8, Trump announced plans to appoint Republican House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy’s nominee, John Nixon, who was the state of Michigan’s budget director as Detroit underwent its own debt crisis, paired with brutal austerity measures. The president also appointed Betty Rosa, New York state’s education commissioner, who had been nominated by Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y. Rosa replaced Ana Matosantos, a Democrat-nominated board member perceived as unfriendly to bondholders.

And Trump indicated he would reappoint Andrew Biggs, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute who filled one of the two seats apportioned to the Senate Majority, and so was originally nominated by Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky.

Last week, Trump moved to fill another seat with a Democrat’s nominee, Antonio Medina, selected by House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., for one of her two seats. Medina, a former pharmaceutical executive and corporate consultant, previously served as head of the Puerto Rico Industrial Development Company, a government entity that promotes private investment in the island. That left one seat vacant.

Left in limbo is board chair David Skeel, a University of Pennsylvania law professor also named by McConnell whose term has expired. Bondholders had expected Skeel to be an ally, but he has so far disappointed them, pushing for a deal that included more debt forgiveness — which in turn has led to pressure by Wall Street firms on Republicans to deny Skeel a reappointment. Former Rep. Sean Duffy, a one-time reality TV star and a Republican from Wisconsin, recently penned the type of esoteric op-ed widely assumed in Washington to be part of a lobbying campaign, urging Trump to replace Skeel. Sources involved in the negotiations suggested to The Intercept that the campaign has been successful, and Skeel is unlikely to be reappointed.

The board’s membership is now majority Republican, but that does not necessarily mean that they can ram through whatever they want. A quorum of five members is required for any plan to advance. Furthermore, Puerto Rico’s legislature has to approve any deal, which is not typically the case with such control boards. Last year, the legislature passed a resolution pledging not to approve pension cuts as part of the deal.

Photo: Al Goldis/AP

For critics of a deal more favorable to bondholders, Nixon’s resume in particular could mean he is as big a threat as Peterson. “Nixon could be more of a risk from the perspective of Puerto Rico because Nixon does have experience in this kind of thing,” said Marxuach. As budget director in Michigan, Nixon played an important role in at least two of the state’s fiscally strapped cities. In both Detroit and Flint, he installed emergency managers who pushed austerity measures — which, in Flint, led to cost-cutting that has been blamed, in part, for the crisis of dangerous drinking water.

Nixon told The Intercept he was not actively involved in bankruptcy negotiations in Detroit and that the Flint water crisis occurred after he left Michigan. “The people of Puerto Rico don’t deserve this,” he said, but added: “The bondholders have a face as well. They’re people who invested in Puerto Rico.”

“There’s a whole pattern of folks that have experience in Michigan that have been enlisted to carry out the same tasks in Puerto Rico,” noted Peter Hammer, director of the Damon J. Keith Center for Civil Rights at Wayne State University Law School in Michigan. For example, both former Michigan Treasurer Andy Dillon as well as Steven Rhodes, the retired U.S. bankruptcy judge who oversaw the Detroit case, have been paid consultants to the Puerto Rican government or the fiscal board.

But to Hammer, given the board’s purpose, the people on it don’t matter so much. “Certain people can make it more embarrassingly crass and more transparent what’s going on and other people can make some façade that this is an exercise of governance,” he said. He and others have argued that in both Puerto Rico and Detroit, austerity measures were enacted that would not be tolerated in majority-white states or cities. For creditors such as the hedge funds that DCI represented, it’s an extractive process that relies on racism, he said. As Hammer put it, “We use the debt instrument to take what we want and disenfranchise the people who are not respected as human beings in the first place.”

Backers of the control board approach point to the requirement for Puerto Rican political approval and say it creates a process that could lead to vast amounts of debt forgiveness for Puerto Rico, which, absent new legislation, no other path would achieve.

López Varona, of the Center for Popular Democracy, which organized the letter to Biden, agrees. “What we have learned is that PROMESA is a tool for extracting wealth from Puerto Rico. It has never been anything else,” he said. “The people in the fiscal control board — that’s their job.”

Critics’ Demands

Ultimately, a “good” debt repayment deal is not what the anti-austerity movement is asking for. The letter to Biden urges the incoming president to advance the repeal of PROMESA and abolish the board entirely. “We have an opportunity with Biden to say, ‘We don’t need PROMESA — what we need is investment and cancellation of the debt,’” López Varona said.

Many have pointed out that much of the debt was illegally issued in violation of Puerto Rico’s constitution and have called for a full audit, a demand that is included in the Puerto Rican organizations’ letter. Beyond the debt, the groups also want long-delayed hurricane relief funds to be released at last to the island, funding for programs like SNAP at least equivalent to what states receive, and the creation of a constitutional convention to help settle the debate over whether Puerto Rico should become a state, break free of the United States entirely, or more firmly establish a status that falls somewhere in between.

Those opponents of the board aligned against bondholders are also invoking the anti-corruption protests that rocked Puerto Rico in the summer of 2016.

“I don’t mind having Peterson on the board. What Peterson shows people is what the board is,” said López Varona. “People will protest and go to the streets if we feel like the board is doubling down on austerity measures to please bondholders.”

Alleen Brown | Radio Free (2020-12-22T19:30:31+00:00) Inside the Scramble for Power in the Board Controlling Puerto Rico’s Financial Future. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2020/12/22/inside-the-scramble-for-power-in-the-board-controlling-puerto-ricos-financial-future/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.