Fed up with foreign wars, Portuguese officers overthrew Prime Minister Marcello Caetano on April 25, 1974. Many former colonies had the opportunity to define their own future.

Angola had been the richest of Portuguese colonies, with major production in coffee, diamonds, iron ore and oil. Of the former colonies, it had the largest white population, which numbered 320,000 of about 6.4 million. When 90% of its white population fled in 1974, Angola lost most of its skilled labor.

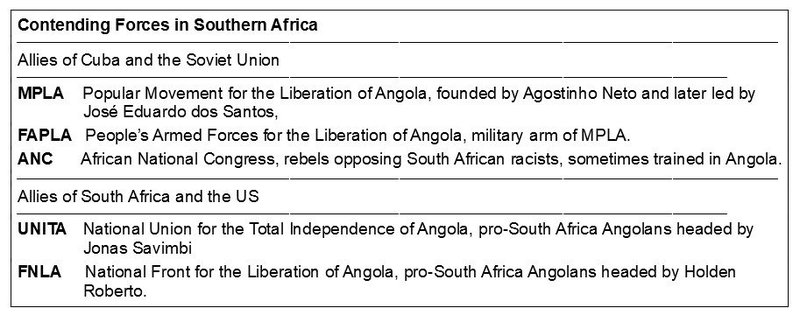

Three groups juggled for power. The Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), headed by Agostinho Neto was the only progressive alternative. The National Front for the Liberation of Angola (NFLA), led by Holden Roberto, gained support from Zaire’s right-wing Joseph Mobutu, a conspirator in the assassination of Patrice Lumumba. Jonas Savimbi, who ran the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), worked hand-in-hand with South Africa’s apartheid regime.

Portugal told South Africa to remove its troops from Angola, which it did by October, 1974. Recently defeated in Vietnam, the US felt unable to send troops. Encouraged by the Ford administration, South Africa returned to Angola within a year.

Meanwhile, Fidel Castro’s representatives met with Neto along with the head of MPLA’s recently organized militia, the Popular Armed Forces for the Liberation of Angola (FAPLA). Not eager to intervene, Cuba declined to give financial support.

The South African invasion began October 14 when many of its white troops pretended to be UNITA forces by darkening their faces with “Black Is Beautiful” camouflage cream. By November, Fidel knew that without help the Angolan capital would fall to apartheid forces and he approved military assistance. The small number of Cubans who arrived were critical in stopping the South African drive to Angola’s capital, Luanda.

Intense hostility between UNITA and the FNLA resulted in the latter being crushed by early 1976, simplifying the conflict to battles between the MPLA and UNITA, with their allies. Cuban troops reached the southern border with Namibia, completely pushing out the forces of apartheid.

Multiple factors propelled Cuba’s entry. The 1959 revolution was so intensely opposed by the US that it became clear that the best defense of Cuba would be an offense. A campaign in Africa would be less likely to provoke a direct confrontation, largely because most Americans did not see Africa as part of their backyard. A huge number of Cubans are of African descent and revolutionaries saw anti-racism as core to their politics. Fidel referred to the anti-apartheid struggle as “the most beautiful cause.”

The second phase of the war

Since the fighting seemed to decrease, the number of Cuban soldiers in Angola dropped from 36,000 in April 1976 to under 24,000 within a year. However, when France and Belgium sent troops to Zaire, Cuba halted its troop withdrawal.

Throughout the Angolan conflict, South Africa and the US ignored international law and acted as if it was perfectly natural for South Africa to dominate Namibia. After South African planes massacred Namibian refugees at the Cassinga camp in Angola in May 1975 US President Jimmy Carter brushed it aside and quipped that “we hope it’s all over.”

Memories of that massacre stayed in the mind of a 12 year old girl, Sophia Ndeitungo: “The first Cubans I ever saw were the soldiers who came” to rescue them. Most Cubans were white, so she “…thought they were South Africans. Later, we understood that not all whites are bad.” Sophia was relocated to Cuba’s Isle of Youth to study. She graduated from Havana’s medical school, married another Cassingan refugee, returned to Namibia, and became head of its armed forces medical services in 2007. For thousands of Black Africans, Cubans were the only white people who showed them any kindness.

Exuberant over the 1980 US election of Ronald Reagan, South Africa stepped up its raids in Angola, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Lesotho, Swaziland, and Botswana. In August 1981 South Africa poured 4000 to 5000 troops into southern Angola with tanks and air support. It expanded tactics to include poisoning wells, killing livestock and destroying food distribution and communications. It was in this context that Cuba began sending 9,000 troops back to Angola during August 1983.

Savimbi: Ally of US and South Africa

Throughout the Carter administration and the early Reagan years, the US increased its flow of weapons to UNITA. As early as 1974, UNITA’s leader Savimbi had established contacts with the Portuguese dictatorship and promised South Africa that he would help them build an anti-communist bloc. Savimbi spoke fluent English, oozed self-confidence, cleverly manipulated his audience, knew just what Americans wanted to hear, and was “without scruple.” In other words, his combination of qualities was a perfect fit for a CIA front man.

Savimbi consolidated his local power by executing village opponents as “sorcerers.” He had total control and did not tolerate dissent. By 1980, in addition to ridding UNITA of those who challenged him, Savimbi had “…the wives and children of the dissenters burned alive in public displays to teach the others.”

Special Forces Colonel Jan Breytenbach saw Savimbi as a “manipulator extraordinaire … As a political leader, he was very good. I would compare him to Hitler.” This comparison to Hitler was not a slighting of Savimbi – it was a compliment, as multiple top South African politicians had been members of pro-Nazi groups.

Among those who overlooked Savimbi’s campaigns of mass destruction was President Jimmy Carter, who took time out of his schedule of human rights advocacy to arrange the flow of secret US dollars to UNITA. In 1985, Steve Weissman summed up attitudes that spanned both parties: “We wanted to hurt Cuba, and we wanted to help people who wanted to hurt Cuba. When Savimbi said that he was ‘fighting for freedom against Cuba’ – this was his trump card. It was impossible to counter it. Savimbi had one redeeming quality: he killed Cubans.”

South African attitudes toward Savimbi fit into its broader perspective of utter contempt for Blacks. Deaths of whites were followed by announcements from the army and newspaper obituaries in the press. Deaths of Black soldiers were not broadcast either by their military superiors or by the press at home.

South African views mirrored those of US politicians. A 1971 amendment to the US sanctions bill by former KKK member and Democrat Senator Robert Byrd (WV) exempted chrome, thereby pulling all teeth from consequences to the white minority government of Rhodesia. A much-publicized July 1986 speech by Reagan lavished praise on South African whites who he said gave great opportunity to Blacks.

Conflicts between allies

Considerable discord between allies arose from the marriage of necessity between Cuba and the Soviet Union. Cuba’s strategy had been for it to confront the better armed and trained South African forces and for Angola’s FAPLA to counter internal enemies in guerrilla warfare. The Soviets believed that FAPLA should develop a conventional army with tanks and heavy weapons to fight South Africa.

Fidel Castro on an official visit to Angola in 1976 | DPA/PA Images

Fidel Castro on an official visit to Angola in 1976 | DPA/PA ImagesBut Angolan troops had virtually no formal education. Officers might have reached the second, third or fourth grade, but the army’s rank and file typically had never been to school and were unable to master sophisticated weapons provided by the Soviets.

While Cuba advocated FAPLA’s concentrating on UNITA, it simultaneously cautioned that the Angolan military should have Cuban backup whenever venturing into territory largely surrounded by UNITA and South African troops. President Neto died in September 1979 and his successor, José Eduardo dos Santos, was often lured by Soviet visions of having a conventional army strong enough to overcome both opposition forces.