ANALYSIS: By Phil Thornton

As chaos flows in Burma, journalists are being forced to hide in plain sight by the Burmese military, writes senior journalist and Myanmar expert Phil Thornton.

Journalists in Myanmar are being hunted and arrested by the country’s military for trying to do their job. Independent media outlets have been raided, licences revoked and offices closed.

To avoid arrest, independent journalists have gone into deep hiding, taken refuge in ethnic controlled regions or fled to neighboring countries. The military and its paid informers trawl through neighborhoods, coffee shops and scan social media for evidence to justify arresting journalists.

The military appointed State Administration Council revised and inserted a clause in the penal code, specifically tailored to gag its critics, politicians, activists and journalists.

Clause 505a of the penal code carries a sentence of three years in prison for actions, criticism or comment that question the coup, cause fear, spread false news or “upsets” government workers.

To stop journalists, photographers and activists sending reports and images of security forces abusing and killing civilians, the military coup leaders ordered telecommunication companies and internet services to shut down their social media platforms.

Brigadier General Zaw Min Tun fronts the military’s press conferences – a list of his titles is impressive: Deputy Minister of Information, head of the armed forces True News Information Team and boss of the military appointed State Administration Council’s media team.

A look at his name card reveals a much darker role – Zaw Min Tun has working directly for coup leader and Commander-in-Chief, General Min Aung Hlaing. Not only does the card boast that General Zaw Min Tun is Directorate of Public Relations, but he is also head of the army’s Psychological Warfare department.

Deceitful work

A Reuters report in 2018 gave an indication of the deceitful work his department of public relations and psychological warfare gets up to when it revealed a book it published on the Rohingya, had used “fake” photographs to claim Muslims were killing Buddhists.

The Reuters investigation into the origin of the photograph “showed it was actually taken during Bangladesh’s 1971 independence war, when hundreds of thousands of Bangladeshis were killed by Pakistani troops”.

The tactic might have been clumsily executed, but it worked, and helped ignite deadly racist attacks against Rohingya people and supported ultra nationalist views at a critical time.

In a more recent move, the Ministry of Information warned on May 4, viewers who watch or receive outside satellite broadcasts were now doing so illegally and were a threat to national security.

The military cautioned viewers on the state-owned television station, MRTV, that “satellite television is no longer legal. Whoever violates the television and video law, especially people using satellite dishes, shall be punishable with one-year imprisonment and a fine of 500,000kyat (US$320).”

Without the support of the shuttered, independent media outlets, getting paid work has been difficult to find, but many journalists took the tough decision to keep reporting, despite fear of arrest and of having internet and phone restrictions imposed on them.

Journalists who spoke to the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ for this article vowed to find a way to keep working and to continue to find ways to deliver news to people both inside the country and to the international community.

Witness to a revolution

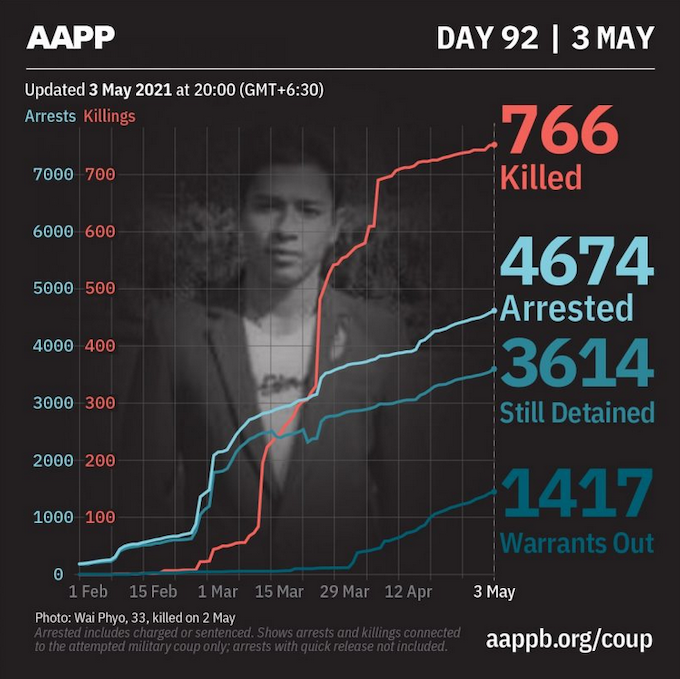

Since the coup began on February 1, independent press freedom has been destroyed. The Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP) estimates 84 journalists have been detained and as of May 3, 50 are currently detained, 25 of these have been persecuted and arrests warrants have been issued for 29.

A later AAPP report, on May 6, said that 772 people have been killed, 4809 arrested and 1478 are now on the run, since the beginning of the coup.

Despite journalists being jailed, tortured and spied on, Naw Betty Han, a journalist with the magazine, Frontier Myanmar, is determined to keep reporting and explained to IFJ why that is, “In the current political situation, it is very difficult for a journalist to live and work in the country. But I will not stop doing my job.

“We’re witness to a revolution. I want to remain at the front of these developments, report on human rights violations and hopefully see the end of the military dictatorship.”

Naw Betty stressed the freedom to report, despite the dangers, is why she keeps working. “Journalism is much more than my job, it’s my mission. I’m willing to take the risk to keep reporting.”

Reporters, citizen journalists, activists and householders have all recorded police and army patrols shooting at and beating unarmed young men and women, ransacking shops and firing live ammunition into homes regardless of who might be hit.

Naw Betty said the military wants to stop any proof of its violence being recorded, “Police and soldiers are everywhere, at temporary checkpoints, on patrols…they check phones, if they find proof of protesting, being a journalist, a photo or a news item that supports the CDM movement… a social media post… they immediately beat and arrest them.”

No journalist identification

Naw Betty said she and her colleagues still working can no longer identify as journalists, “We have to delete our phone data when we go out in the field gathering news. Police and soldiers break open houses at night to surprise check the guest list. If you do not open the door, they will break in and arrest you anyhow.

“A former DVB reporter was beaten last week at his home after a search of his home and no evidence was found.”

Naw Betty is well aware of the risks of being arrested. In 2020 while investigating a multibillion-dollar Chinese investment on the Thai Burma border she and a photographer colleague were detained by a Burma Army sponsored militia – masked, handcuffed, driven to a rubber plantation and beaten, before finally being released.

“I am scared of being arrested and faced with the violence in interrogation. But I am positive, I am more afraid that I would not be able to continue as a journalist. I know that I am in danger of being arrested, but I want to keep working as a reporter.”

Naw Betty told IFJ the military, aided by its paid informers, are systematically increasing its crackdown on its opponents, squeezing their ability to move and forcing them into taking more dangerous risks, not knowing who to trust.

Naw Betty said “I’m worried about them [informers], I moved to a different place as soon as the coup happened, hopefully I can stay safe. Journalists in Myanmar are now trying to be as low profile as possible, but when there is a compelling situation, we have to go out to report and take risks.

“We are targets…74 journalists have been arrested and charged under 505 (A). Arrested journalists face physical and mental violence during interrogation before being sent to prison.”

We’re willing and ready

The military’s revoking of licenses and outlawing independent outlets has made it hard for many journalists to find paid work. Naw Betty said journalists have turned to freelance to try to earn a living from their reporting, “Many journalists I know are now faced with financial problems as they have no regular income anymore.

“Some photojournalists have tried to string for international news agencies, but the opportunities are limited – most are struggling with no income.”

A scan of social media postings by advocates offers links to what could become stories of interest to international media, but military refusal to give unfettered access to verify or follow-up accusations of corruption, rumours of security forces looting and bomb attacks has made it to difficult to follow-up.

Naw Betty encourages international media organisations to hire local journalists: “Give locals the chance to work on part-time assignments. We all are willing and ready to support on the ground reporting with international and foreign journalists – we can work together.”

Our priority is to keep broadcasting

Than Win Htut, a senior executive with Democratic Voice of Burma, now working from the edges of a neighboring country, said his priority, after his Yangon DVB operation was shutdown and outlawed, was to get back to operating at full capacity.

“Many journalists are on the run or in hiding. We have to review our network. When they closed us down we lost a lot of our capacity to broadcast – our newsroom, studio, talk show, on-line, research and data analysis.

“We now have to reorganise, rebuild and reintegrate. We need a new studio, live reporting, get journalists on the street, it won’t be easy.”

Than Win Htut’s operation has a whole range of challenges posed by the geography and weather. The monsoon wet season is about to hit his new mountainous location, flooding small rivers into deep, fast flowing hard-to-cross torrents.

The wet season brings dengue fever, malaria and dysentery, difficult at the best of time, but highly dangerous when the nearest medical help is a day away.

Than Win Htut said while searching for new premises maintaining security is of critical importance during forced exile. “They’ve cracked down on mobile phone services, internet is limited, the independent flow of information is blocked, arresting journalists, they won’t stop. We have to take our security serious. Many young journalists don’t have the experience of having to work in secret, going underground. Constantly changing your name, location, passwords, sim-cards, even your phone.”

Than Win Htut is worried sophisticated cyber surveillance equipment and technology the military acquired from Russia, China, Israel, US and Europe is now being used by the military to track and hunt its opponents.

Risks taken

“We have to take the position, the more you know the more the risk you are to yourself and to others. If a journalist gets arrested, you don’t know what they’ve been forced to give up during interrogation.

“We also have to now reconsider how we use photographs and footage of people protesting and of journalists.”

Than Win Htut stressed, international correspondents can endanger local journalists by not knowing the context, especially when following up leads on those arrested.

“You might be trying to help, but the arrested will be trying hard to not identify as a journalist or activist, but by running stories and photos you might be confirming the military’s suspicion someone is a journalist – that makes it dangerous.”

Than Win Htut is concerned the unity between journalists who went to neighbouring countries and those who stayed behind doesn’t divide. “We mustn’t let divisions stop us being united. We need to support each other, whether we are working from inside or outside the country, we’re all in this together.”

You’re either underground or with them

Toe Zaw Latt, an Australia citizen and production director of DVB, spent more than 80 days covering the military coup. With the help of the Australian Embassy in Myanmar, Toe Zaw Latt managed to leave his Yangon place of hiding and return to Australia last week.

Now in the middle of his 14-day quarantine in Adelaide, Toe Zaw Latt talked with IFJ about the ongoing anti-coup protests and the hounding of journalists by security forces.

Since the beginning of the coup, Toe Zaw Latt has been in daily contact with IFJ. He explained: “Most of the independent media have been closed down. Only independent papers left on the street before I left were Eleven Media and Standard Times. Journalists have to face a new threat from plainclothes Special Branch using stolen civilian cars to patrol neighborhoods.

“They turned up at a freelance journalist’s house to arrest her. She wasn’t there, so they took her husband instead. If they can’t arrest the journo it looks like they’ll just take a family member in their place.”

Toe Zaw Latt explained how journalists cannot do anything that identifies them to the police or army.

“No cameras, no notebooks, disguise yourself each time and what you are doing, make sure you carry nothing that can be used to identify you as a journalist and learn how to hide your phone.

“Smart phones are still good in the field, but we need to train young journalists to become more adept with using them to report and they need to know how to get footage out to be broadcast.”

International media interest

“Toe Zaw Latt is concerned that international media continues to maintain an interest in what’s happening with the daily civilian protests and they buy content from local providers.

“It’s important international media agencies keep employing or buying footage from local sources. Freelancers are risking their lives to get footage, they should be paid for it.

“Media news agencies should make a paid contribution and not just lift content off the internet. Journalists are helping each other. Those who are getting paid are sharing with those who aren’t.”

Toe Zaw Latt is impressed by the enthusiasm and resilience shown by activists and students to publish and broadcast news despite military threats of long prison sentences.

“Lots of underground media has emerged since the coup. Student activists fighting the military’s internet blackout have published newsletters – Molotov, Toward and Revolution. The National Unity Government are planning Public Voice TV, underground ethnic youth are running Federal FM and ethnic Mon media produce Lagon Eain.

“I respect their courage in fighting the military’s version of the truth and rejecting their misinformation.”

A senior ethnic journalist spoke to IFJ about the restriction she faces on a daily basis.

“No one can work in the military government-controlled areas. Special Branch have our photographs and our personal details. We’ve put up with it for years. Our houses have been visited, family interrogated.

Risks too stressful

“Some of our colleagues resigned, because the risks were too stressful. They felt they’d be no use to their families if they were in jail.”

The senior journalist explained news coverage now has to be underground.

“It’s either that or you report according to their instructions and that’s total rubbish, just propaganda. All they want is for journalists to legitimise the coup. If you stand up to that your only choice is to go underground.

“Some might play the margins, start by not covering anything sensitive.”

The senior journalists said media could be split into two groups.

“Those willing to be mouthpieces for the military. They don’t run stories upsetting the military and use terms dictated by the State Administration Council. Then there’s what the military classify as radicals.

Our websites are usually blocked, our reporters cannot operate on the surface, we have to go underground and anyone against the military is a target.”

Ethnic journalist difficulties

To give an indication of the difficulties ethnic journalists are working under, from March 27 to May 5, the Karen National Union report its soldiers were involved in 407 armed battles with the Burma Army.

Ethnic journalists told IFJ fighter jets have flown into Karen controlled territory 27 times and dropped 47 bombs , killing 14 civilians wounding 28 and forcing as many as 30,000 people into makeshift jungle camps.

“This is an emergency, it needs reporting and international aid. Villagers’ rice stores have been destroyed as well as homes, schools and clinics.

“To report we have to avoid landmines, army patrols that shoot on sight and the military’s paid informers and special branch who we have to think have our photographs.”

Phil Thornton is a journalist, author and senior adviser to the International Federation of Journalists in South East Asia.

This content originally appeared on Asia Pacific Report and was authored by Pacific Media Watch.

Pacific Media Watch | Radio Free (2021-05-07T23:34:21+00:00) Myanmar: If independent media dies, democracy dies. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2021/05/07/myanmar-if-independent-media-dies-democracy-dies-2/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.