Has your approach to making your work changed over the years?

Really, until fairly recently, I always felt clueless, which is just the most terrifying feeling. Recently I became resigned to what I do and recognize what I do. I accepted my work for what it is and that’s a huge change for me. Huge. That happened about a year ago.

What led to that acceptance?

It’s more of an interesting career answer to that question, which is that a lot of people were looking at my work and liking my work, people I respected, and they were all sort of pointing at the work and saying, “Yeah, this is it. Just relax and do it.” I don’t know why I always felt so uneasy like, “Oh, it’s not good enough.” Some kind of weird self-doubt, even though the work always really looks very confident. I think it’s very natural for some reason. In my head, it was never good enough and I was like “Oh, is this really what it is?” A really great museum curator and I had a kind of serious conversation, I don’t know, maybe two years ago. It started where he was like, “Pam, this is what you do. Just choose it. You have to consciously choose it and you’re going to feel much better.” I don’t know how he knew to say that to me because he’s not a painter, but I guess he’s looked at a million paintings. I guess the big thing that’s happened to me and my work is probably more in my mind than in the work itself.

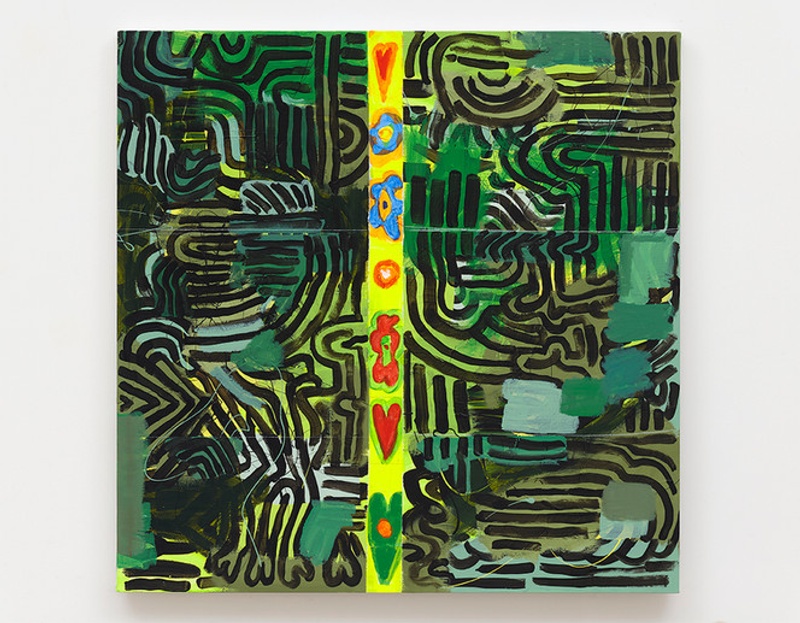

Untitled, 2021. Acrylic and enamel on canvas. 30 x 30 inches.

I know you took a long stretch away from your work years ago.

Yes, I mean, somewhere between 10 and 15 years. I didn’t take time away from making work, but I took time away from having a career when I was raising my kids. I just couldn’t handle everything, between the little kids and we lived on a hobby farm in Vermont with live animals I had to take care of. I taught art at a couple of boarding schools and at a couple of colleges, visiting artist gigs and things like that. Very little showing. I probably was in a couple of group shows in New York during that time, and a couple of weird shows in Brattleboro. I just completely took showing my work out of the equation because I was way too beside myself that everything was falling apart and I wanted to do the best job with my kids and I had to work. That other thing just had to go. It seemed indulgent to be doing that. I wasn’t making money doing it so what the hell? So yeah, a long time, a very long time…

Actually, this art dealer named Kathleen Cullen called me out of the blue. I mean, when I say out of the blue, like 10 years from when I last had seen her or showed in New York. She opened a gallery and was like, “I really need an artist like Pam Glick.” I’m like, “Okay, whatever that means. What kind of artist am I?” So I had a show there after a long time. She took the train up and it was pretty amazing. It made me feel so much better. There’s a lot of despair when you feel like what you like doing the best is kind of so far away from what you’re actually doing. Here’s a funny anecdote. I was one of the last people to have an iPhone and they’re like, “Oh, you can pick a screensaver,” so I had a photograph of Grandma Moses because I thought, “Oh, well, she started when she was 80 and I already have a head start.” She was who I always had in my mind. People were like, “Why do you have a picture of George Bush on your phone?” You would not believe that they look so much alike so that always made me laugh. She’s one of my guiding lights.

Do you have any insights to share with artists who aren’t working in the way they would like to?

Because I’m older and I’ve gone through these phases, I would say that it’s always there for you, always waiting for you. It doesn’t go away so don’t be worried if you have an all-consuming job or you’re raising kids or both. Most people are doing both like I did. Your work is always there and if at all possible, just always draw because that keeps your mind going forward. Even if you’re going forward by the tiniest bit, it still is something and it makes you feel really good. It’s really there to help you connect with whatever your secret power is and you just want to acknowledge whatever that is and try to encourage it.

Even though you had those years away from showing, you were always making things. Have you ever felt stuck when it comes to making?

I don’t think that’s ever happened. I mean, not that everything is good by any means, but there’s always drawing. I have plenty of really talented friends, painter friends, that get blocked. They can’t paint for long periods of time. I just never had that happen. I think it’s because it’s my favorite thing to do, like eating pie or something, for people who like eating a lot. For me, that’s the most fun thing to do so how would that ever be a problem?

What is your process of working on the paintings?

I work on them on the floor and I work on them up against the wall. After the color, I do the initial drawing with pencil and levels, sometimes tape. It doesn’t always even end up being the painting, but I kind of think of it as a playground that I set up and then I’m going to do things inside of that. That’s how it’s very specific, what is the top and what’s the bottom. I don’t ever think it gets turned around. The swirls and stuff of paint is usually from when it’s on the ground and I’m painting. I use cans of water-based enamel paint so sometimes, it just comes off the brush and makes those skins of paint which I like a lot or I would be more careful. I think they become a part of a type of drawing. It’s like they’re creating another space but I kind of ignore them and I don’t pay attention to where it’s going. I don’t want it to look like it’s on purpose or like a decorative element.

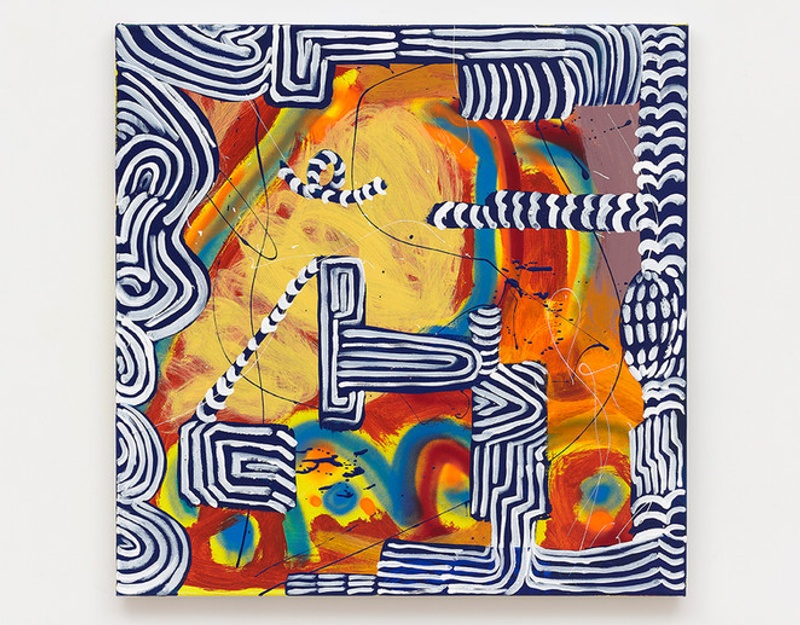

Parallax Niagara-USA-Canada, 2018. Acrylic and enamel on canvas. 30 x 30 inches.

Many of your paintings are titled Niagara-USA-Canada, referencing your proximity to and love for Niagara Falls as an artist who grew up in Buffalo, lived elsewhere for many years, and has since returned. Will you talk about place and your work?

I actually have literally loved Buffalo only in the past year, and that’s a funny thing because I’ve always loved things about it and the people here, but I lived in New York for such a long time and always felt most at home there. When I moved back here, it was for family reasons. I’m pretty literal and decided, “Well, I’m here, I guess I’ll just start doing some Niagara Falls paintings.” I haven’t had a big studio like this in ages.

I do feel like one of the overpowering things here is that we’re on the border of Canada. I’ve always just had this huge sense of, “Oh, there’s this whole other country just five minutes away,” like when you’re driving in Europe and suddenly you’re in Lichtenstein or you’re in Holland. For us being on the border of Canada was always a big thing and it always felt very expansive because of that and because of the water, the Niagara River and Niagara Falls.

The water is why the sky looks the way it does. It’s definitely a sky that is by the ocean or a big body of water. The series of paintings since I’ve been [back] here—I started calling them Niagara-USA-Canada because, “Oh, that’s really where I am.” I think a lot of great literature and paintings are tied to where they were done. Cormac McCarthy, a favorite author of mine from your neck of the woods [in New Mexico], would not be writing those books if he was in Connecticut. That would be totally different. So they’re not really about place—I’m not really painting anything about Niagara Falls—but whatever spirit guide of that place is there, that is what kind of gets inside the work.

Untitled, 2021. Acrylic, enamel and graphite on canvas. 48 x 48 inches.

Do you keep regular hours in your studio?

I do. I’m like a banker. I get here at 8 and work till 5 or 6 sometimes. I’m very, very regular. I don’t like working at night. Although once I start doing it, I get the energy but I’m a really morning energy person for working. The fresh air, the light, everything.

How do you know when something is done?

I have a few friends and family that I’ll just send a picture to. They’ll say something like, “Wow,” or “Not sure,” or something like that. But I don’t really completely trust any of them either. There’s a couple of them that are like, “Don’t touch it, you idiot. Are you kidding?” And I’ll have no idea it’s that. This constant iPhone thing is a blessing and a curse. I’m not a great sleeper so at night, I’ll listen to an audiobook or something and I’ll look at my pictures of what I’m working on and sometimes I’ll just see exactly what I need to do or I’ll say, “Oh my god, that’s so good. I did that? It’s done.” Sometimes, you just need distance from it. It’s hard to see it when you’re right inside of it.

Untitled, 2021, Acrylic, enamel, flash, wax pencil and graphite on canvas. 30 x 30 inches.

You’ve taught art on and off over the years and I imagine there have been some non-artists in your classes. Did you have any go-to assignments?

My favorite group of students, in terms of the high school kids, were from a ski racing academy in Northern Vermont. Those kids are gifted athletes and half their day is schoolwork and the other half is skiing and dry land training. They’re like Olympic athletes or at least they’re being treated like that. They’re running up hills with rocks and backpacks and pulling sleds with rocks and doing all kinds of box jumps. Both of my kids went to school there, so they hired me to start an art program because of that. One of the kids had a full scholarship and the other one was very good but we had to pay money, so with me teaching, I’d get some salary but also it helped pay for the tuition.

These kids were so used to being coached and told like, “Oh, if you just tuck your left elbow…,” the tiniest nuance with skiing—they just knew how to listen to directions and do it. I had some kids there, honestly, that could just go to New York and have careers. They were so free and teachable. It was really fun.

I didn’t give them assignments any different than at the Putney School where those kids all already think they’re artists or their parents are, and they’re like, “Oh yeah, we have a Cézanne at home.” They’re very privileged and exposed to a lot of art and they’re creative kids. These athletes were very physical, but also very open to being coached and wanting to please their teacher.

The first class is in the Fall and there’s always Queen Anne’s Lace around, which is by far the most complicated flower in the world. It’s made up of a billion, tiny little flowers that are kind of shaped like daisies but they’re itsy-bitsy. The first class was always like, “Okay, we’re going to do the very hardest thing first. No other thing will be this hard,” and so they’d have to really look at it so carefully and draw it. I would talk very little in the beginning of the class but just get them set up. They were just mind bogglingly, beautiful drawings. Absolutely, you cannot go wrong with that assignment.

Another assignment I liked doing early in the Fall because I usually was working at boarding schools—but I think this would work anywhere—is drawing their bedrooms at home. Those were usually really cool.

I’d count how many classes altogether there would be for a semester. Let’s say there’s going to be 30 classes. I really tried to come up with 35 things like that and they would tie together because I have my style and my way of doing things. I would show them this list, “Okay, we’re doing all this stuff, maybe not in order but I’ll see how everyone’s doing. We’ll pick some of these things.”

This was a fun assignment: on a nice day to go outside and make a drawing, but you can’t use pencils or pens or anything. They had never seen a Rauschenberg with a tire track, and a lot of times they did that, they ran over their paper with their bikes. They always came back with very interesting work. They’d go to the dining room and get grape juice or something. I could think of a lot of fun things that they did, rubbing flowers on it, and they’d come back and it all ended up looking like a [Mark] Rothko. They didn’t know the connection to modern art.

A collector friend of mine gave me a hundred old auction catalogs and I tore the pages out and I’d have them in a pile and say, “Pick one of these things and copy it.” It would be anywhere from some early American painting or a Jean-Michel [Basquiat] or Arthur Dove, whatever, every type of thing. They usually pick something that was like what they did without knowing that’s what they were doing.

Then I’d have them put it away and then do a copy of it from their head. Those auction catalogs had prices on them and these kids were like, “A million dollars for that?” They just had no idea. They’re like, “Whoa, I could actually get a job doing this.” It was really funny seeing them react to the financial connection to this stuff. I didn’t hide that. I just always thought, “Oh, that’s an interesting part of this lesson here. They’re learning about this.”

Untitled, 2021. Acrylic, enamel, flash, wax pencil and graphite on canvas. 30 x 30 inches.

What has been most surprising to you on your creative path?

Really, how little my work has changed since I was really young. I look at a lot of my old paintings from when I was 18 or 20 and I’m like, “Oh my god, the whole painting is right there. Why didn’t I just see that a long time ago?”

Pam Glick Recommends:

Audiobooks. The written word is so inspiring and so different from what I do.

This content originally appeared on The Creative Independent and was authored by Annie Bielski.