A leaked report describes significant deficiencies in the safety and integrity of the pipelines used by the U.S. military to shuttle fuel to U.S. Marine Corps and Air Force warplanes in Okinawa Prefecture, Japan. As early as 2014, the military discovered monitoring system flaws and dangerous leakages in the pipelines, some of which run beneath civilian communities, but it waited four years before initiating repairs and has never alerted Japanese authorities. The dangers have only come to light thanks to a whistleblower who made public a report produced under contract for the Defense Logistics Agency Energy, or DLA-E, the Department of Defense agency that supplies fuel to military facilities.

Map of the main fuel storage sites on Okinawa.

Image: DLA

Published in March 2015, the report details inspections of vapor monitoring systems that detect fuel leaks along the 100-plus miles of pipelines in the prefecture. The results showed 43 of the 60 monitoring systems were inoperable due to problems like broken sensors and alarms; in at least one case, the alarm and sensor system were missing entirely. The devices are supposed to notify the local DLA-E compound of leaks, which can cause environmental contamination, explosions, and fires.

The disclosure comes on top of recent revelations that the military may have hidden details of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, contamination on Okinawa from a senior member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, including information pointing to the possible exposure of children at a civilian school.

“The report needed to be made public to show that the U.S. government is not following the policies set up to run the pipelines safely,” the whistleblower, who was granted anonymity to avoid professional reprisal, told The Intercept. “The government ought to have come out and been open about these problems. Many people on Okinawa don’t even know these pipelines are running beneath their feet.”

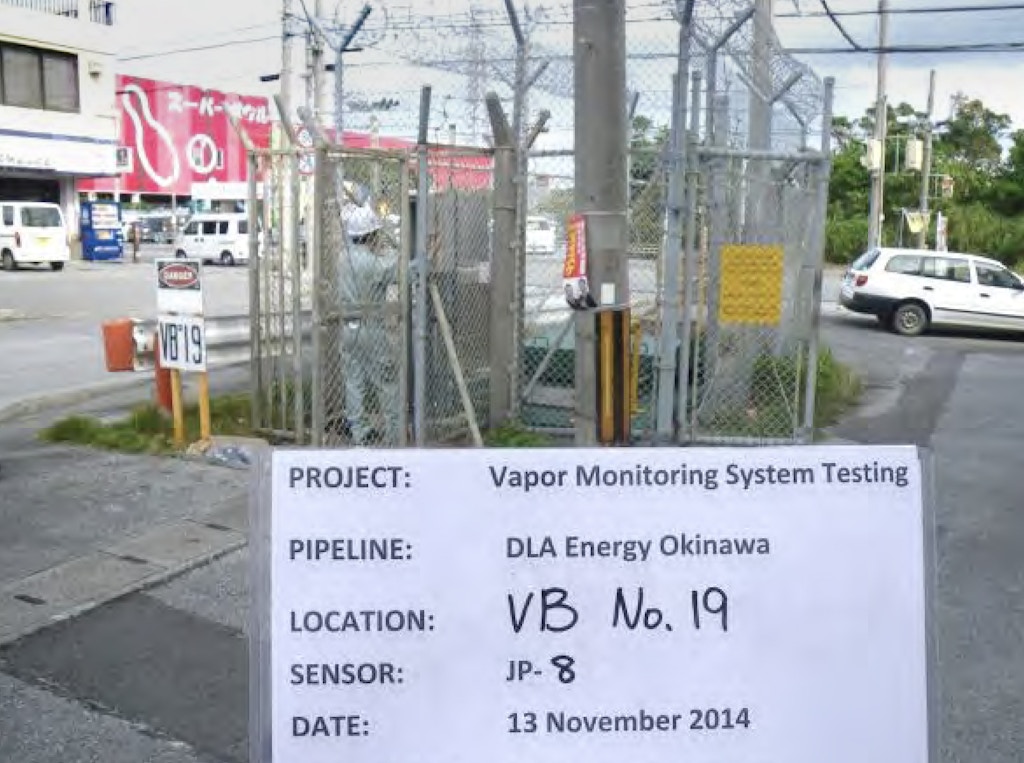

The pipelines travel below five municipalities, carrying more than 90 million gallons of aviation fuel per year to the island’s U.S. Air Force and Marine Corps bases. One of the report’s photos shows a monitoring post near a bowling alley in a civilian area of Okinawa City, where the site’s sensor failed checks and faced problems that inspectors described as “significant.” In their final recommendations, the report’s authors estimated repairs to the system would cost $252,900, and they advised retesting within six months to comply with the DLA-E’s guidelines.

Inspection of a monitoring post for the military’s pipeline in Okinawa City in November 2014; this check revealed “significant” problems.

Photo: DLA

But the agency did not start repairs on the broken monitors until 2018, according to U.S. Forces Japan. In a statement, USFJ said, “DLA does not possess records on the system prior to 2014” — meaning that the military could have been operating the system without adequate safety protocols since its installation in 1983.

“All DLA Energy facilities in Okinawa are secured and inaccessible to local personnel. Therefore, even in the event of a fuel release and a monitor malfunction, there is no danger to the safety of Okinawa residents,” the USFJ spokesperson added. But this statement is inaccurate: The pipelines run beneath densely populated residential areas, which would be seriously impacted if a leak occurred.

USFJ explained that it had installed an automatic fuel monitoring system, referred to as AFHE, in 2014. “Monitoring of the system is 24/7 by the AFHE system, our control room, and round-the-clock maintenance teams that patrol and inspect our fuel system,” the spokesperson said.

But the whistleblower disputes these assurances. “The system still isn’t safe,” they told The Intercept. “Staff ignore alarms when they go off and the communications system doesn’t work. Wildlife gets into the boxes and damages them. There are wiring problems plus the monitoring boxes are rotten and rusted. It’s like having a broken smoke detector at home, but much worse. One day, people living near the pipeline might wake up in a lake of fuel.”

At the time of publication, USFJ had not responded to the claims.

If there were similar problems with fuel pipelines at military bases within the United States, said the whistleblower, the Environmental Protection Agency would be expected to get involved and attempt to remediate the issues. In Japan, there is no such civilian oversight.

Such lack of accountability has long angered Okinawans who, for decades, have campaigned for an overhaul of the Japan-U.S. Status of Forces Agreement, which allows the U.S. military to operate outside Japanese laws. Under SOFA, the U.S. military completely controls access to its 78 facilities in Japan — 31 of which are in Okinawa Prefecture — and only rarely does it grant access to Japanese authorities. On-duty service members are exempt from prosecution for damage to Japanese property, and the military is not required to remediate contamination on land returned to civilian usage.

“Because of SOFA, the U.S. military can evade responsibility for such problems. It can hide environmental damage because there is no mechanism to force the U.S. military to open up the information or tell the Japanese government,” said Manabu Sato, a professor of political science at Okinawa International University, Ginowan City.

“It’s like having a broken smoke detector at home, but much worse. One day, people living near the pipeline might wake up in a lake of fuel.”

Compounding the issue is Japan’s longstanding tendency not to take seriously Okinawans’ grievances about being forced to host so many military facilities, he said. “It’s just the latest in a long series of similar incidents.”

In recent years, environmental infractions committed by the U.S. military on Okinawa include radioactive contamination from depleted uranium, massive spills of fuel, and the discovery of 108 barrels of dioxin-tainted herbicides buried beneath a children’s soccer pitch. The military often hides these problems. Many have only been made public via requests filed under the U.S. Freedom of Information Act.

Photo: Richard Atrero de Guzman/NurPhoto via Getty Images

The most extensive contamination comes from PFAS chemicals contained in firefighting foams. Near Defense Department facilities on Okinawa, farmers’ fields, natural springs, and rivers are polluted, and the substances have contaminated the drinking water sources of 450,000 residents. Such contamination is pervasive in the United States, too, but unlike at home, where the federal government has begun to compel the Defense Department to implement surveys and clean-ups, on Okinawa there has been no such push for accountability.

One explanation for the inaction could be the U.S. military’s concealment of details of the Okinawa contamination from American elected officials.

Recently, emails obtained via FOIA from the U.S. Marine Corps show that the military misled a senior member of the Senate Armed Services Committee about PFAS contamination in the prefecture. In autumn 2018, the office of Sen. Jeanne Shaheen, D-N.H., requested information from the military about whether it had identified PFAS contamination on Okinawa, how it was mitigating and remediating the problem, and how it was cooperating with local governments to protect surrounding communities.

The military’s responses were inaccurate, incomplete, and minimized the severity of the contamination.

On October 18, 2018, the military sent an email concerning contamination levels from Marine Corps Air Station Futenma, a major air base in the populous central Okinawan city of Ginowan. It stated:

tests were conducted at the Fire Training Pit and two storm water conveyances at MCAS Futenma. The Fire Training Pit results showed levels for PFOS and PFOA consistent with the historical use of the site for training with AFFF. Concurrent samples taken from storm water conveyances upstream and downstream from the airfield were below 5 ppt for PFOS and PFOA.

The comment implies that contamination from the fire training area is not impacting off-base communities, but it is misleading. The storm water test sites that registered the very low levels of contamination were located almost a mile from the fire training area, so these numbers did not prove the site was safe. A Marine Corps email dated November 20 of the same year contained “a corrected graphic,” acknowledging the sample sites and the fire training area were “not hydrologically connected.” It also revealed severe PFOS and PFOA contamination of 28,800 parts per thousands, but whether this information was sent to the senator’s office is unclear.

The Marine Corps additionally did not disclose that the corrected map indicates that water from the contaminated training site has been flowing toward a local elementary school. When the existence of the map was reported by the Okinawa Times on December 9, parents of children who attend the school expressed their outrage and demanded that the school grounds be checked for contamination. In 2017, a window frame from a U.S. military helicopter fell onto the same school’s grounds while children were taking an outdoor physical education class.

“Where should our children walk?” asked a local mother. She told the Okinawa Times that she was worried about both the sky above the school and the ground beneath it. “Schools have the image of being safe, but that’s not true here.”

Another email obtained via FOIA from the Marine Corps includes a summary of the Air Force’s reply to Shaheen. It contains misleading statements implying that the Japanese government was allowed to conduct PFAS checks within Kadena Air Base, and that Tokyo had concluded the base was not responsible for the contamination of Hija River, a source of the island’s drinking water. Neither is accurate.

The emails obtained from the Marine Corps omit information the military possessed at the time of Shaheen’s inquiry. Severe PFAS contamination had been detected in groundwater and the fire training area at Kadena Air Base, and natural springs sacred to Okinawans’ Indigenous religious communities near Marine Corps Air Station Futenma have been polluted with some of the highest levels of PFAS ever detected in Japan since widespread checks began in 2016. The emails also do not address Shaheen’s inquiry about the military’s cooperation with local governments. Since 2016, Okinawan authorities have requested access to inspect Kadena Air Base, but such requests have still not been approved.

For the past two years, the U.S. Air Force has further hindered investigations into PFAS contamination at Kadena Air Base by stalling FOIA requests and refusing to process administrative appeals on the delays.

At the time of publication, Shaheen’s office had not responded to requests for comment. U.S. Forces Japan and the Defense Department did not explain whether they have provided Shaheen’s office with updated, accurate information.

“The military thinks that if they can hide its PFAS contamination from the Senate Armed Services Committee, then they will be safe from any investigations. But once the information is revealed, they will be in a very bad position,” said Sato, the Okinawa International University professor.

“The government of Japan doesn’t want to anger the U.S. — it wants to please them in any way,” Sato added. “Tokyo has been ignoring these environmental problems for a long time, but as long as they occur on Okinawa, it dismisses them as ‘only Okinawa issues’ and doesn’t raise any fuss.”

This content originally appeared on The Intercept and was authored by Jon Mitchell.

Jon Mitchell | Radio Free (2021-12-20T10:00:08+00:00) U.S. Military Hid Fuel Pipeline Flaws From Public in Okinawa. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2021/12/20/u-s-military-hid-fuel-pipeline-flaws-from-public-in-okinawa/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.