Introduction

For the most part socialists and members of organized religion seem to be opposites. After all, didn’t Marx say religion was the opium of the people, the heart of a heartless world? But has it always been this way? Socialists in the 19th century had very different ideas about the importance of mythology, ritual, and art. But could19th century socialist engage in these activities without getting caught up in supernatural ideas and reified images? This article discusses the efforts of William Morris, Walter Crane, and the Knights of Labor to bring heaven down to earth.

Orientation

The need for art, myth, and ritual in socialism

Despite its seemingly secular orientation, literature scholar Terry Eagleton has said that socialism has been a greater reform movement than religion, in fact, it has been the greatest reform movement in human history. But in order to achieve these reforms, economic reorganization of society by itself was not enough to move people. There also needed to be socialist culture, artistry, aesthetics, symbolism, rituals, and mythology. However, you would never know it if you looked at socialist practice for most of the 20th century, especially in Germany and in Yankeedom. Stefan Arvidsson says this about the classical description in historical materialism. The description of how different modes of production have emerged and how socialism of necessity will precede capitalism has something glaringly mythic about which modernist socialists never capitalized on. Karl Kautsky, the socialist Pope of the Second International, went so far as to state that socialism had no ideals to realize, no goals to reach, everything was a secular movement, with no myths and no rituals. Yet all movements, secular or spiritual, need appeal to collective emotions, awaken hope while giving structure to disappointments, sadness and anger. Romantic socialism did this well in the 19th century but why was it so reluctant to claim the same legacy in the 20th century?

Enlightenment and Socialist Criticisms of religion

In his book The Style and Mythology of Socialism: Socialist idealism, 1871-1914, Stefan Arvidsson names three of the most typical left-wing criticisms of religion:

1) Rational – the claim that religion is false. Religion contradicts the factual description of reality offered by the natural sciences. There is no god in heaven; magic is built on faulty premises and faith healing doesn’t work. This was the Enlightenment criticism.

2) Political – priests and the church claim divine authority to control crowds and legitimize the right to their privileges and that of political and economic elites.

This can be seen in Catholicism and Protestant elites in Europe and the United States. It is present in Islamic elites and the Brahminical Hinduism of Modi. It is present among Zionist elites in Israel. This slant also came out of the Enlightenment.

3) Ideological – this is the criticism of Feuerbach and Marx. It affirms that God is the alienated creativity of the masses. What people cannot do on earth, they project onto heaven. It’s the promise of a world to come in order to sugarcoat the lack of a prosperous world in this life.

I believe all these criticisms are right. The problem is:

- They are undialectical and do not ask the question of why religion has maintained itself for thousands of years in spite of these criticisms. Surely from a Darwinian point of view, if religion was just irrational, a political trick or an ideological mystification keeping people in mental chains, why didn’t natural selection filter it out?

- Religion is held at arm’s length. All the methods of religion – myths, rituals, holidays, sacraments, pilgrimages, art, altered states – were hot potatoes, too hot to handle. This unfortunate circumstance has kept socialists in the 20th century from learning from and using these spiritual tools in a non-reified, non-superstitious way.

My claim

The purpose of this article is to say:

- Religious art, myth, rituals, symbols and techniques for altering states of consciousness should be taken over by socialists and used to our benefit.

- The Knights of Labor and some socialists the 19th century knew how to do this and we must learn from them.

Plan for the article

The plan of this article is first to ask if socialism is a religion. My response if that I don’t think it’s a religion. Then I will examine the characteristics of romantic socialism in the first half and second half of the 19th century. I then turn to the Christian mythology of the Bible, the positivism and the religion of humanity and lastly the pagan claims of Jules Michelet and the work of Ricard Wagner. I then discuss socialist art, including the work of William Morris and William Crane. Next, I examine the political application or romantic socialism to the organization of the Knights of Labor.

In the last part of my article, I will discuss how romantic socialism was gradually replaced by modernist socialism. I close with a discussion of how romantic socialism missed the boat by relying on the slave religion of Christianity for its inspiration rather than a pagan tradition which is much more consistent with the anti-authoritarian nature of romantic socialism.

Is socialism a religion?

There is a beehive of conservatives who were all too happy to claim that, contrary to its atheist claims, socialism is a religion in its own right. In the Psychology of Socialism, Le Bon points out many quasi-religious phenomena of socialism like feasts, saints, martyrs, canonical texts, revolutionary myths, holy symbols and ritualized speech. Georges Sorel argued that the value of socialism does not rest with its material success or failure. Socialism as a kind of myth which gives people hope. It is fair to say that like any religion, socialism has a list of mythological events – Thomas Müntzer leading the German peasants, John Ball leading the English peasants in England, and Robin Hood (myth or not) robbing the rich to give to the poor. In the 19th and 20th centuries we had the Paris Commune, the storming of the Winter Palace in Russia, worker’s self-management during the Spanish Revolution and the life of Che to name a few. Even now, socialism still depends on symbolism – the red rose of the social democrats, the red star of revolutionary socialism and the encircling A of anarchism all show that socialism needs images to inspire.

Modern socialists, especially Marxists, have resisted the idea that it may be appropriate to label socialism as a surrogate religion because they claimed that socialism is scientific. In addition, as a Marxist I would claim that socialism is not a religion because the root meaning of religion is to bind-back, implying that something was lost. What was lost is a community which bound classless, pagan, and tribal societies together. Religion is a social emulsifier designed to paper over class differences. As Marx writes, it is the heart of a heartless world. Socialist attempts to create a classless society are designed to create a real binding, a heaven on earth, a return to primitive communism, but on a higher level. But polarizing socialism to be the opposite of religion was not the way socialists of the 19th century framed things. These socialists understood that religious means could be used to create socialist ends.

Romantic socialism

Romanticism is not an easy term to define and it covers the entire political spectrum.

Arvidsson names five “colors” of romanticism. Blue romanticism is the dreamy, sublime artistic romanticism of Schiller, Shelley and Byron. There is white romanticism which is a religious and clerical tradition of revolutionary romantic lodges, and Christian socialists and the Knights of Labor. This form of romanticism wanted to take the individualist blue romanticism to the masses. Red and black romanticism is the romanticism of the anarchists, Sorel and artistically the symbolists’ writers. Green romanticism is the romanticism of the radical arts and crafts – Morris, and life reform movement. Yellow romanticism is what I would call the art-for-art’s sake of Oscar Wilde.

1st half of the 19th century

The socialism of early 19th century, what Marx and Engels would have called utopian socialism, began with the experiments in communist living of Robert Owen and Charles Fourier. These societies operated on a small scale and combined farming and artisan work, prior to the specialization of labor. Here workers did many more parts of the job than what happened in the specialization of labor in the second half of the 19th century. The emphasis in this community is characterized by Arvidsson as fraternity, intensity, and authenticity. These values were most clearly embedded in the work of Jean Rousseau, John Ruskin and later, William Morris. What made them so different from the socialism of the end of the 19th century was their incorporation of religion with its myth, rituals and art.

2nd half of the 19th century

Surprisingly, the thinker who had the most impact when it came to spreading the expression “religion of socialism” was the person whom Marx characterized as “our philosopher”, Joseph Dietzgen. His was a kind of the Feuerbach-inspired religion of humanity. For Dietzgen, this new religion has two parts:

- scientific knowledge wherein nature is tamed; and,

- science through “magic” – that is, the creative power of labor. It is magic because nature is transformed through work. Work is the name of the new redeemer.

Some advocates of the religion of socialism wished to appropriate socialist hymns, socialist saints, socialist sacraments, socialist rituals and even a socialist Ten Commandments.

Even funeral rites began to be ritualized within the religion of socialism. The great revolutionary socialist Ferdinand Lasalle believed that his political meetings were reminiscent of the very earliest religions. In the early years Wagner, the Viking revivalist, dreamed of creating an opening for revolutionary change with his epic opera. Later on, we will revisit this period and examine the practices of the Knights of Labor. Feeding forward a bit, in the early 20th century Russian authors Maxim Gorky, Anatoly Lunacharsky, and Alexander Bogdanov seized the initiative to create a “god-building” movement. The idea was to merge positivists and left-wing Hegelian religion of humanity, a-la Dietzgen and Wagner.

Mythology

Christian mythology

Socialists in the 19th century were not squeamish about drawing on the Bible to justify their movement. The books of the prophets have been the greatest inspiration for people to fight back. These books tell of rage against the shortcomings of their leaders and condemn social injustices. The man who did the most to link Jesus to the labor movement was George Lippard. For him, Jesus was a worker with class-consciousness. Famously, there is the painting and description of how Jesus cast out all the money-changers from the temple and overthrew the tables. The biblical figure of Mammon become the name of the god of money. Later in classical mythology Pluto is also the god of wealth, involving money and securities.

In Mark (in the Bible), there is the saying it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God. The socialism of Blatchford and Keir Hardie was wrapped up in biblical language. At some point, Debs says “Just as a missionary goes out and preaches to the heathen in foreign countries, so we socialists got on soap boxes and persuaded people that industry could be run for use and not for profit.” (Page 216 of Style and Mythology of Socialism). The president of the union for miners in Illinois preached about the divine origin of labor unions. An English Baptist preacher declared that the capitalist market economy is more in keeping with the gladiatorial than a Christian theory of existence.

Positivism and the religion of humanity

There were a number of famous Christian socialists who were not waiting around for the life hereafter. During the 19th century they included Henri de Saint-Simon, Étienne Cabet, Wilhelm Weitling, Moses Hess, and later in the century, Leo Tolstoy.

In the case of August Comte, it was the human being that were to be worshiped as a deity in the making. Over time, Arvidsson says positivism developed into a full-fledged religion, having even its own calendar composed of writers and inventors like Dante, Gutenberg, Shakespeare, while excluding Christian figures. This religion of humanity included rituals, temples and mythical heroes.

It is easy to dismiss the Christian socialist as not real. But it may surprise you to know that some of the members of the Second International were trying to integrate religion with socialism. For example:

One of those most driven to establish a religion of humanity in Great Britain was Morris’ friend and partner within the Social Democratic Federation and Socialist League, E. Belfort Bax (212). Bax writes:

The religion of the future must point to the immorality of the social man. The religion of socialism can contribute to extending the life of the individual. (224)

What Bax meant was that the immortality of social man would be embedded in the processes and results of building socialism on earth. The individual is immortalized in the collective creations they built in the bridges, buildings, books, paintings, and weavings that became the fabric of the new world long after the individual is dead.

Witches and pagans

Jules Michelet was one of the first historians to consider witchcraft not merely as a religious controversy but as a resistance movement of the peasantry. Arvidsson says he introduced the witch as a proto-socialist whose Chthon-ic gods and goddesses were seen as a viable spiritual alternative to a Christianity which seemed increasingly to have come into conflict with scientific truths.

Just as Michelet brought in pagan witches, William Morris, the revolutionary, was nostalgically fascinated with the Viking Age, especially with anti-royalist Iceland. He studied Old Icelandic, which lead to a translation of the Völsunga Saga. Later when we examine the art of Walter Crane, we will see his work as a longing for a sensuality hedonism and paganism. It belongs to the primitive tradition of Rousseau and Fourier. We can see his paganism when Crane imagined the laborers’ holidays as being a more Dionysian affair.

All primitive magical rituals use all the arts in order to create an altered state of consciousness. This included costume making, music, myth, storytelling, mask-making and dance. For most of western history, with the exception of within the Catholic Church, the arts became separate from the sacred. It was Richard Wagner who reunited them in his epic theatrical productions which included drama, opera, and ritual. It is tempting to dismiss Wagner because of his right-wing turn towards the end of his life, but he was once a leftist:

In Richard Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerk, beautiful music is wrapped together with anarchist revelations about the corrosive forces of power and wealth, and the innate idealism of natural human beings. (142)

Wagner says:

We should never be careful not to underestimate the yearning by many people to be part of something big and beautiful. Fellowship was all well and good, but men needed something to whet their appetites. (143)

Unfortunately, the modernist socialists never understood this.

Wagner’s use of Norse and Medieval texts for his opera The Ring, which he began working on during the revolutionary days of 1848 when he fought with Bakunin on the streets of Dresden. The Ring is about the curse of greed. Regardless of Wagner’s right-wing turn, Anatoly Lunacharsky, the first Soviet minister of culture and education, liked Wagner. In 1933, the 50th anniversary of Wagner’s death, Lunacharsky paid homage to him by describing the composer as a musician who gets the spirits to gather. A famous Swedish example of the anti-capitalist use of Norse mythology is Viktor Rydberg’s interpretation of the Edda poem Grottasöngr.

Socialist Aesthetics

Idealist aesthetics in the 19th century claimed that the task of art – whether it was poetry, literature, music, or painting – was a way to uplift us and to point the way to the ideal. They wanted to help transform people into more virtuous human beings.

William Morris

John Ruskin was mercilessly critical of civilization and culture and felt that it oozed of modern decay and decadence. His most driven spokesperson was the great English socialist, William Morris. Morris distinguishes society from civilization and says he hates civilization. For Morris, socialism and anarchism replaced Ruskin’s “blue” romantic elitism. He wanted to align those ideas with Ruskin’s romantic criticism of civilization. Morris’s ideals certainly stemmed from Ruskin and Walter Pater’s Renaissance ideas of beauty. Morris used to say art is man’s expression of his joy in labor. All work should or could be art. Beautiful objects are created by beautiful working environments. For Morris, the reward of labor is life. An ideal society is a society that is not only encouraged by art but is in and of itself a work of art. For Morris, socialism implied a complete philosophy of life that comprised the Good and the True as well as the Beautiful.

At the end of the 1889 into the 1890s, William Morris and the arts and crafts movement stood for the first radical artistic change. Morris and his disciples were not only concerned with graphic design but also with full aesthetic programs for handicraft, architecture, city planning, conservation, art, and literature. The aim was:

- The transformation of life

- The transformation of the conditions of physical labor

The purpose was that life and work cease to be alienated. For Morris, articles become beautiful when they are created from the joyful laboring of a rich personality.

Walter Crane

According to Arvidsson, no one meant more for the socialist culture of visual arts in the late 19th to early 20th century than Walter Crane. Crane joined the Socialist League under the leadership of Morris and Eleanor Marx Aveling. He marched in pro-Irish demonstrations, which would be later known as Bloody Sunday. In his painting, Socialist Valkyrie, the peace of socialism triumphs over the warring knights of liberalism and conservativism. Many of his political posters, Solidarity of Labor; Labour’s May Day 1890; the Worker’s Maypole; The Cause of Labor and the Hope of the World have been copied. For the first time in the history of the world, a socialist iconography had been created. Crane believed that artists learn from the handicraft traditions of folk culture. The artist should look downward towards the lower class and to nature for inspiration, not upwards towards some kind of ingenious spiritual inspiration. The engraving The Triumph of Labor (1891), was Crane’s most famous, commemorating the socialist May Day and the definitive image of English socialism. In Walter Crane’s painting of Freedom, the angel frees humanity from both the animalistic power of the king and the transcendentalism of the priests. In another painting, the famous French icon Marianne leads workers to attack the class enemy.

In a May Day parade, socialists carry Crane’s prints of The Triumph of Labor, which Arvidsson describes in the following way:

In the thick of the procession walks a winged bringer of light…Liberte Marianne…The personifications…bleed into one another. Beside her, a boy leads a mounted farmer and they are closely followed by Monsieur Egalitarian and Fraternity…

The figures of the French Revolution are followed by the two oxen, a woman with a cornucopia – perhaps Demeter and a young man playing a flute (Pan or a satyr) – and a young woman dancing with a tambourine. (maenad) (192)

Even leading Austrian Marxists consciously tried to infuse May Day with religious solemnity and messianic feelings.

Socialist Romanticism in Politics: The Knights of Labor

Description of the Material Vision of the Knights of Labor

The Knights of Labor was the largest and the most powerful labor organization of late 19th century in North America. Skilled and unskilled laborers were welcomed, as were women and black workers. The order tried to teach the American wage earner that s/he was a wage earner first, a brick layer, carpenter, miner and shoemaker after that. He was a wage earner first, and a Catholic, Protestant and Jew, white, Democrat, Republican after.

Surprisingly for a labor organization, in the spirit of fraternity, politics and religion were forbidden topics of conversation in the congregation’s building.

The Goals were:

- To make industrial and moral growth, not wealth, the true standard of individual and national greatness.

- To secure for the workers the full enjoyment of the wealth they create, and sufficient leisure in which to develop their intellectual moral and social faculties.

Their constitution included the following:

The implementation of safety measures for miners; prohibition of children under 15 from working in factories; a national monetary system independent of banks; nationalization of the telegraph, telephone and railway networks; the creation of cooperative businesses; equal work for equal pay irrespective of gender; a refusal to work more than 8 hours per day. (p. 91)

The Knights felt it was immoral and blasphemous to live off the work of others. Toil was one thing, but to be exploited was another. Under capitalism, they struggled with how to pay tribute to essential and natural creative work without defending alienation of labor. They believed labor was the only thing that generates value.

Knights of Labor as a Secret Society

The Knights of Labor was no ordinary labor organization. They wanted to bring together humanity, hand, head, and heart. The Knights used medievalist mythology as part of the overall trend towards a Gothic revival. Guild socialism was a notion that Middle Ages was valued because it was believed that economics and ethics had not yet been torn from each other. There was a fraternal secret of laborers with rituals, special handshakes, devotional songs, and mythologies. Officials within the order thus acted as a kind of priests and there was a pledge to be loyal to the order and not to reveal any of its secrets. Devotional songs were sung and organ music filled the air. Cooperation is portrayed as divine. The lodges were like seeds that are scattered over the earth and like all seeds, they struggle to germinate and grow. For the Knights of Labor, the philosopher’s stone was no philosophical process of turning dross matter into gold. It was the process of work itself.

Here is a recommendation for a poetic recitation during the opening ceremony:

Notice the combination of matter and spirit throughout the poem: granite and rose, archangel and bee, flames of sun and stars. Notice a pantheistic view of God. This was a theological orientation associated with political radicalism during the 19th century:

God of the Granite and the Rose

Soul of archangel and the bee

The mighty tide of being flows

Through every channel, Lord from Thee

It springs to life in grass and flowers

Through every grade of being runs

Till from Creations radiant towers

Thy glory flames in stars and suns

In 1879 Terrace Powderly was elected grand master workman and he began reworking the images of socialism used for agitation purposes. For example, in the painting of the Great Seal of Knighthood, humanity joins together in the form of a circle around God’s triangle in the Great Seal. Arvidsson points out that Powderly added some new touches. Instead of abstractions like creation, justice, humanity, he added labor. He changes the triangle of God on the inside to the process of laboring: of production, distribution and consumption. The pentagon is changed to the five days of the work-week. Finally, the hexagon on the outside is changed to a symbol of various tools.

For the Knights the handshake was secret, but the manner of the shake was rooted in labor. The emphasis on the importance of the thumb was intended to reinforce how important an opposable thumb is compared with other fingers. The thumb makes possible humanities such the use of tools at work, in the fine arts and in craftsmanship. Lastly the production of buttons, pins, and portraits of the founders and of Powderly were made. He was first American working-class hero of national stature.

The Fall of Romantic Socialism

According to Arvidsson, after the devastations of the Franco-Prussian war and the Paris Commune, romanticism was on the run in Europe. In the second half of the 19th century romantic socialism had to compete with other cultural styles. For romantic socialism, it was the ideal of the good that was designated in symbols. But alongside it there were now artistic movements of realism and naturalism for which the ideal was not what was good, but what was true – including the dark side of social reality. In the light of the naturalistic outlook with its scientific eye for the less beautiful side of humanity, romanticism seems meaningless, moralizing and out of touch with reality. With Darwinism, the time had become ripe for vitalism, where life was seen as a struggle, where the strong and the sound, not the honest, noble and beautiful triumphed.

Oscar Wilde was the mediator between Morris and Crane’s romanticism on the one hand and modernism on the other. Wilde wanted to link socialism with aestheticism and wanted to revolutionize society so that the life of people will be to become artistic. With Wilde, aestheticism returned to romanticism in emphasizing the importance of beauty, but with a difference. For romantics what was beautiful had to have a particular content, namely, the cause of workers. But for aestheticism it was the principles of beauty independent of its application.

From fraternal order to trade union

For the founders and many of the leaders of the Knights of Labor, the single-minded pursuit of higher salaries seemed narrow and short-sighted. They strove instead to create a higher culture. A sizable chunk of workers’ experience is dismissed if ritual and fraternity is ignored. But attitudes towards fraternalism as a form of struggle began to change at the turn of the century. The mythic and religious aspects of the Knights of Labor were toned down as a consequence of the Catholic Church’s criticism and threats. With the ritualistic dimension missing for the workers, the requirements for direct material success of labor organizations became more pressing. The experience of knighthood was to be replaced by membership in pragmatic oriented and often reformist or relatively apolitical, modern and secular trade unions. Within the political life of unions, socialist modernism suggested that fraternal organizations existed for the benefits of the leaders. They were seen as forms of social careerism for these “high priests”. In the US, it was the modern labor union and socialist-oriented political parties that replaced socialist fraternalism. Socialism came to be understood as economic and less and less to do with culture. Modernist socialists like Marx, Engels, and later Kautsky all took this stand.

From Fraternal order to Fabian Think Tank

In Britain Fabianism became a bridge between life reform and culture-oriented socialist romanticism and the social democratic parties that followed. The Fabian Society was founded in 1884. Members included Sidney and Beatrice Webb, Edward Carpenter, Havelock and Edith Ellis, H.G. Wells, Annie Besant, George Bernard Shaw, and Walter Crane. Early on, they cultivated a kind of life-style socialism, including vegetarianism. But they were not interested in ritual or dramatization. It became important for the Fabians to distance their modern socialism from bohemian lifestyle socialism and primitivist flirtations. The Webbs and Shaw founded the London School of Economics and Political Science in 1895. Political reform, which was foreign to the Knights of Labor, was another tendency that grew with the parliamentarian successes of socialist parties after they became legal. This impressed the Fabians.

From co-producer of culture to consumer of culture

Beginning in the middle of the 19th century, mass advertising and department stores began to spring up, first in Paris and then on the east coast of Yankee cities. By the end of the 19th century, the rising consumer culture pulled the rug out from under both the Knights of Labor and the Fabians. Instead of listening to lectures and singing in the assembly halls, laborers started to visit the emergent theaters, amusement parks, and cabarets more frequently. Leisure was transformed from largely participatory to more passive, consumer activities. In the 19th century, people marched in parades. By the early 20th century, they cheered parades from the sidelines. Successful entrepreneurs were the new heroes in the kingdom of trade. The story lines contained within advertising and their logos replaced myth. Shopping sprees became the new rituals. Buying luxury items became modern talismans. Economists became soothsayers and prophets of economic growth. Old worker flags and banners of real people turned into stylized and geometrical forms.

From Utopia to Dystopia

The 19th century was the great century of Utopias whether in practical communist societies or theoretical novels. Edward Bellamy, William Morris, Jules Verne and H.G. Wells were different, with some supporting high technology and others not. However, all were optimistic. Twentieth century modernism was all pessimistic beginning with Jack London’s Iron Heel. In the first half of the 20th century utopian literature became dominated by three disillusioned ex-socialists: Yevgeny Ivanovich Zamyatin’s We in 1921; Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World in 1932; and Orwell’s 1984 in 1949.

Romanticism ended with World War I and lost out as a cultural style. However, it was rebirthed with the beats after World War II, the rise of the New Left, the counterculture of the 60s, and the New Age and Neopagan movements that began in the 1970s.

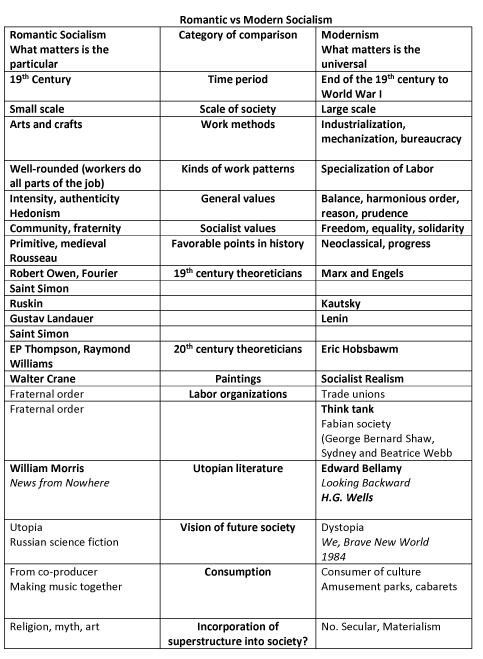

See the table at the end of this article which summarizes the differences between romantic and modern socialism.

Witchcraft and paganism as socialism’s lost opportunity

In the middle of this article, I mentioned the work of some progressives and socialists for whom witchcraft and paganism offered resources for hope. As I mentioned earlier, Jules Michelet claimed that witchcraft in the Middle Ages and in Early Modern Europe was a resistance movement of the peasantry against both the Church and the landlords. Later, William Morris saw the anti-royalist Vikings as inspiration enough for him to study the language of Iceland. Furthermore, the artwork of Walter Crane had many pagan elements in it. Lastly, Richard Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerk and The Ring are both about the curse of greed and corruption. But even more importantly Wagner combined his tales in epic proportion by saturating the senses with pageantry, music, dance, drama, and ritual. This was a throwback to the pagan rituals of tribal societies and more elaborately in agricultural states. Why wasn’t this seized on by romantic socialists more often instead of relying on the slave religion of Christianity for its inspiration?

The pagan tradition of tribal societies is much more consistent with the anti-authoritarian nature of romantic socialism. What I want to focus on is the Neopagan movement started by romantics in the middle of the 18th century and blossomed in the 1970s. I’ve written a number of articles agitating for a new pagan-Marxist synthesis. In my article New Agers vs Neopagans: Can Either Be Salvaged for Socialism? I identified many categories where there is full agreement between Neopagans, democratic socialists, anarchists and the various types of Leninists. Here are some of the commonalities from that article. Here is what both romantic and modern socialists are missing out on.

Western magic and matter as creative and self-regulating

Paganism and the western ceremonial magical traditions have deep roots in the West, from ancient Roman times through the Renaissance magicians, alchemists, Rosicrucians and up to the Golden Dawn at the end of the 19th century. All these traditions were committed to in some way redeeming matter. Matter was seen by all magical traditions as creative, self-regulating and immanent in this world. Pagans are either pantheists or polytheists. Like socialist materialists, matter is seen by pagans as real, rather than evil or an illusion. There is clearly a relationship between pagan pantheism and dialectical materialism.

Nature and society are objective forces that impact individuals and only groups change reality

Like socialists, Neopagans would never say individuals “create their own reality”. Neopagan nature is revered and must be taken care of. The forces of nature or the gods and goddesses actively do things to disrupt the plans and schemes of individuals. How would socialists react to this? Very positively. All socialists understand nature and society as evolving. Socialists understand that individuals by themselves can change little. It is organized groups which change the world. Since much of Neopagan rituals are group rituals, there would be compatibility in outlook here as well.

Embracing the aggressive and dark side of nature and society

Neopagans could never be accused of being fluffy or pollyannish. There is a recognition that there is dark side of nature. These dark forces must be worked with and integrated. Socialists would agree with this, but as the darkest force on this planet is capitalism, socialists would disagree that there can be any integration with capitalism.

Importance of the past: primitive communism and pre-Christian paganism

The past is very important to Neopagans mostly because of what Christianity did to pagans throughout Western history. The past is also very important to Marxists because primitive communism was an example of how humanity could live without capitalism.

Most Neopagans, like Marxists, are very pro-science

Chaos theory, complexity theory that would attract Neopagans is very much like Marxian dialectical materialism. While the Gaia hypothesis would be a stretch for materialists, Vernadsky’s Biosphere would be welcomed by Neopagans. Lastly, even primitivist anarchists are very interested in science fiction and how society could be better organized in the future.

Commonality between Wiccan covens and anarchist affinity groups or cells

There have never to my knowledge been pagan cults. Many Neopagans are generally an anti-authoritarian lot and organizing them can be like herding cats. Many Neopagans, like socialists, are very anti-capitalist anarchists and Neopagan witches.

Politically many wiccan pagans like Starhawk’s Reclaiming have organized themselves anarchistically with consensus decision making. The most predictable anti-capitalists in Neopaganism are wiccans. Economically, the work of anarchist economist David Graeber would fit perfectly for Neopagan witch anarchists.

Commonality between Neopagan goddess reverence and socialist feminism

Wiccans are also very pro-feminist and some are organized where the goddess values of women are predominant. All this is good news for socialists, since Margot Adler has said that about half of the roughly 200,000 Neopagans are wiccans. A program for a socialist feminism could be easily taken in stride by most Neopagans.

Sensory saturation and inspired altered states of consciousness

I have saved these categories for last because this is the area of Neopaganism that might be the most actively contested by socialists, but it is also the area that I think Neopagans have the most to teach socialists. As I’ve stated in other articles, a good definition of magick is the art and science of changing group consciousness at will by saturating the senses through the use of the arts and images in ritual. Socialists are likely to dismiss this as dangerous because it sweeps people away. They are also likely to confuse this with religious rituals which religious authorities control their parishioners for the purposes of mystifying people and asserting control over them. This is a big mistake. Not all rituals are superstitious reifications. and when done well, are a way to empower people and built confidence. People in egalitarian societies, the ones Marxists call primitive communism, understood this. The pagan holiday Beltane May Day corresponds to socialist May Day celebrations around the world and a great place for the meeting of these movements. We need socialists in the arts, especially in dance, music, choreography and play-writing to join with Neopagans who are already good at this.

• First published in Socialist Planning Beyond Capitalism

• First published in Socialist Planning Beyond Capitalism

This content originally appeared on Dissident Voice and was authored by Bruce Lerro.

Bruce Lerro | Radio Free (2022-02-18T14:49:45+00:00) The Mythology, Ritual, and Art of Romantic Socialism. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2022/02/18/the-mythology-ritual-and-art-of-romantic-socialism/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.