The whistleblowers who have alleged systemic corruption in the Environmental Protection Agency’s New Chemicals Division have refrained from releasing the names of the managers and other agency officials who they say have repeatedly interfered with the chemical assessment process — until now. Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, or PEER, the group that represents the EPA staff scientists, has decided to release four of the complaints it sent to the EPA inspector general and The Intercept on the whistleblowers’ behalf, complete with the names of three staff members who were involved in many of the alleged instances of interference: Todd Stedeford, Iris Camacho, and Tala Henry.

All three EPA officials have played a significant role in pressuring scientists to downplay the risks posed by products the agency is assessing, according to voluminous documentation the whistleblowers have provided to The Intercept and the EPA inspector general over the past eight months. Henry serves as the deputy director for programs in the agency’s Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics, which includes the New Chemicals Division, and Camacho is a branch chief responsible for chemical assessment in a division of the same office. Stedeford, an attorney and toxicologist, served as a senior science adviser in the agency’s Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics until May, when he left to work at Bergeson & Campbell, a law firm that helps chemical companies navigate the regulatory process.

Camacho, Henry, Stedeford, and Stedeford’s employer, Bergeson & Campbell, did not respond to multiple inquiries related to this article, including emails to Camacho’s and Henry’s EPA email addresses, and Stedeford’s work address and to his employer. The EPA press office said that, because of a pending investigation by the EPA Inspector General, “Drs. Henry and Camacho do not have a comment at this time.”

The whistleblowers, all scientists with doctorates who worked in a division of the EPA that assesses the hazards of new chemicals, have alleged that these agency officials pushed them to expedite the approval of certain high-priority chemical submissions at the behest of industry. Their complaints to the EPA inspector general, which they also submitted to members of Congress, have contained specific records to back their allegations.

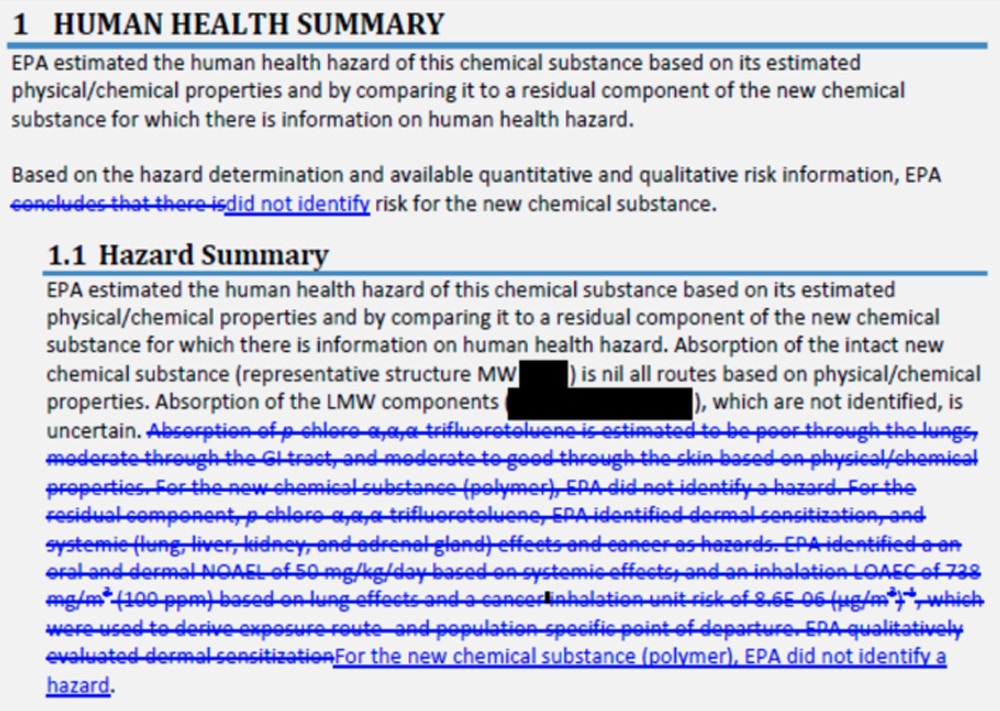

The first complaint, filed in June, explained that all four whistleblowers experienced having chemical hazards they identified — including developmental toxicity, neurotoxicity, mutagenicity, and/or carcinogenicity — removed from assessments. According to a complaint they submitted to the EPA inspector general in early August, the whistleblowers met with opposition from all three named officials in their effort to accurately account for exposure to certain chemicals. On one occasion, according to the complaint, Stedeford revised a report, changing a finding of neurotoxicity after speaking to a representative of the company that made the chemical. Another of their complaints, submitted to the inspector general in late August, described Camacho as deleting hazards from an assessment without the permission of the scientist who worked on it to make the chemical seem less hazardous. And in a complaint filed with the inspector general in November, the whistleblowers documented the case of a chemical used in paint, caulk, ink, and other products that posed health risks, including the risk of cancer. In the latter case, a risk assessor noted the hazards in the assessment, but Henry changed the document to say that the “EPA did not identify risk” for the chemical.

Screenshot: The Intercept

Screenshot of an EPA draft assessment of a paint containing PCBTF, a chemical that has been shown to cause cancer. The initial assessment identified the health hazards associated with the chemical. But a version that whistleblowers say was revised by Tala Henry, deputy director for programs in the EPA’s Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics, strikes the specific health risks and concludes that the “EPA did not identify a hazard.”

Michal Freedhoff, assistant administrator of the EPA’s Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention, which includes the New Chemicals Division, told The Intercept that she is ready and willing to respond to cases of wrongdoing. “I am fully committed to taking appropriate actions in response to substantiated cases of harassment, scientific integrity violations, and recommendations from the inspector general,” Freedhoff said in a telephone interview.

Tim Whitehouse, PEER’s executive director, said the organization made the decision to release the documents containing the detailed allegations and officials’ names in part because of a threat Freedhoff reportedly made during a Zoom meeting she held in January with environmentalists who work on toxic chemicals, which Henry also attended. During the meeting, Freedhoff told representatives of environmental organizations that if they publicly suggested individual EPA staff members had been influenced by industry they would no longer be welcome at the regular meetings with the agency, according to several people who were on the call. Freedhoff said that criticism about the individual agency officials was causing her staff to have low morale and that while she welcomed substantive policy suggestions, personnel matters and internal agency disputes were off limits. PEER stated that all “confidential business information” was redacted from the complaints prior to being released to The Intercept.

In the interview, Freedhoff acknowledged making the statement to the advocates but said that her intent was not to stifle criticism. “It’s not about being disagreed with,” said Freedhoff. “It’s about being personally attacked, having the agency be personally attacked, and having individual staff and managers be personally attacked. And I think there’s a really big difference between a personal attack and a substantive disagreement.”

Freedhoff, who joined the EPA in January 2021, described her stance as supportive of agency employees who are still reeling from interference with environmental regulation that was rampant during the Trump administration. “I think the staff, both career and managers, just went through what is probably the four worst years of their professional careers,” she said. “I’m not going to have my staff, after all that they’ve been through, sit through meetings with people who are calling them corrupt.”

Some who were aware of Freedhoff’s comments said they found them disturbing. “This was just a very naked threat to deny access to people who say things she doesn’t like,” said one environmental advocate who attended the January meeting.

“This was just a very naked threat to deny access to people who say things she doesn’t like.”

Kyla Bennett, PEER’s director of science policy, said that she believed Freedhoff was choosing to support some of her staff members at the expense of others. “Freedhoff is assistant administrator for OCSPP. That includes staff and managers. Our clients are her staff too. But she has clearly chosen a side,” she said. Bennett added that she saw the interference with dozens of chemical assessments that the whistleblowers have documented as both a substantive issue and a personnel issue.

Freedhoff’s comments to the advocates came weeks after six major environmental organizations sent a letter to her and EPA Administrator Michael Regan in December asking them to make several changes in response to The Intercept’s reporting on the whistleblowers’ allegations. While acknowledging that the agency had already taken steps to improve scientific integrity in the chemical assessment process, the green groups, including the Natural Resources Defense Council, the Environmental Defense Fund, the Center for Environmental Health, and Earthjustice, argued that the EPA hadn’t gone far enough. The letter asked the agency leaders to clearly condemn and immediately halt the “improper practices” laid out by the whistleblowers. The environmental advocates also asked Freedhoff and Regan to commit to immediately removing staff from supervisory roles “where the evidence shows that they engaged in serious misconduct that failed to conform to EPA scientific integrity principles or otherwise violated agency policies.”

Noting that the EPA had not spoken out about the conduct described by the whistleblowers since the allegations were first made in early July, the representatives of the environmental organizations asked Freedhoff and Regan to take a stand against corruption of the handling of pre-manufacture notifications, also known as PMNs.

“We urge that EPA staff be sent a clear message that the alleged actions will no longer be tolerated, that scientific misconduct in the PMN program will no longer be rewarded and that the overriding goal of PMN reviews will be public health and environmental protection, not rapid approval of new chemicals in order to placate industry submitters,” the letter stated.

“If EPA is serious about scientific integrity, it can’t just sit on its hands.”

Under President Joe Biden, the EPA has repeatedly emphasized its commitment to investigating violations of scientific integrity. But the administration’s fight to clean up the agency has been met with criticism for its reluctance to punish wrongdoers. Accountability has again proved to be a sticking point in the case of the whistleblowers, three of whom were removed from their positions in the agency’s New Chemicals Division during the Trump administration after speaking up about the pressure they faced to downplay chemical risks. Meanwhile, the agency staff who have been accused of interfering with science have been allowed to stay in their jobs in that same division.

Freedhoff defended her choice not to remove the accused officials from their posts by contrasting her decision with the last administration’s handling of staff they saw as problematic. “The previous leadership would remove staff and managers from the roles, divert them to other parts of the agency or OCSPP, or marginalize people who raised concerns about policy decisions, and that honestly left the entire workforce, both the staff and managers, feeling completely unsafe and unprotected,” she said. “I can’t just remove people, staff or managers, from their roles without a normal, standard EPA personnel process.”

But one former senior EPA official who asked not to be identified by name said that transferring managers who have been the subject of well-documented complaints that they interfered with the regulatory process is not comparable to the Trump administration’s removal of scientists who were trying to do their jobs. “I don’t see how you could equate the two situations,” said the former official. “Based on the whistleblower complaints, there are credible and detailed claims with documentation that supervisors engaged in violations of scientific integrity. If EPA is serious about scientific integrity, it can’t just sit on its hands.”

PEER’s Bennett said that delaying action until the conclusion of an investigation by the inspector general has allowed the manipulation of the assessment process to continue and has left the whistleblowers vulnerable to ongoing retaliation. “We are so grateful for the IG’s deep dive into these very complicated allegations. But because we’ve given them so much information, it’s going to take them a lot of time to do it justice and come up with a conclusion,” said Bennett. “In the meantime, while they are investigating, these problems are continuing unabated, which is affecting the public health of every American. And it’s making our clients miserable.” Since coming forward with their allegations, the whistleblowers have been denied advancement within the agency and excluded from opportunities to serve on certain committees and interesting projects. “They are treated as pariahs,” said Bennett.

Asked whether she was aware of any retaliation against the whistleblowers, Freedhoff declined to answer.

Bennett also noted that Freedhoff still works very closely with Henry and that her comments clarified the need for the organization to take additional steps to protect the whistleblowers. “We were working under the mistaken assumption that the Biden administration would take some kind of action to ensure that American health was protected and that our clients were protected until such time as the IG made a final determination,” she said. “But because Dr. Freedhoff so firmly sided with her managers before the IG has come to a conclusion, we felt we had no choice.”

Freedhoff has the daunting task of both reversing the environmental rollbacks made under President Donald Trump and addressing the corruption of the regulatory process that was widespread under the last administration. In some cases, she has been quick to act: In February 2021, the EPA pulled the assessment of the PFAS compound PFBS, citing breaches of scientific integrity. And in March of last year, just seven weeks after she joined the agency, Freedhoff sent an email to staff in the Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention announcing that “political interference” had also compromised the integrity of the registration of the pesticide dicamba and a risk evaluation of the chemical TCE.

Notably, she made these announcements before the EPA’s Office of Inspector General released its final report on political interference in the dicamba registration process. Freedhoff has taken a sharply different approach to the whistleblowers.

“I want to know why Freedhoff admitted flat out that the dicamba, TCE, and PFBS assessments were tainted by violations of the Scientific Integrity Policy within a month or two of starting but the whistleblowers’ allegations are ‘just differences of opinion,’” said a current EPA staffer, who asked to remain anonymous because of fears of retaliation. “There is no way she was handed a finalized IG report on those three decisions on her first day in office. What gives with the double standard?”

Freedhoff said that in the cases of PFBS, dicamba, and TCE, she and her staff had been very involved in presenting evidence of interference to the inspector general. “We all knew what that report was going to say because it was based on stories that my staff had told the IG,” she said. “They were public already. They weren’t under litigation themselves at the time, and most importantly, the interference in question wasn’t directed by anybody who remained employed at the agency.”

Some environmental advocates said they were sympathetic to Freedhoff’s situation. “She’s juggling a lot — really wanting to fix things, having a staffing crisis, having all these ongoing investigations, and trying to get done all she wants to get done,” said Lori Ann Burd, environmental health program director at the Center for Biological Diversity. Burd, along with several other environmental advocates who work closely with the EPA, also said that Freedhoff has been responsive to their substantive concerns.

But others said they were disturbed by Freedhoff’s attempt to prohibit certain critics from attending meetings. “It’s very, very problematic,” said the former EPA senior official who asked to remain anonymous. “It’s part of the agency’s environmental protection mission to hear from all stakeholders, including those that offer critical feedback.”

One of the environmental advocates present at the January meeting took issue with Freedhoff’s characterization of her statements as defending EPA staff members. “I believe it is a false characterization,” said the advocate, who asked to remain anonymous because of fears of retaliation. “None of the environmental groups who were at the meeting and who signed on to that letter have attacked anyone at EPA personally. Freedhoff is creating a false issue here and trying to seize the high ground.” Instead, the advocate said, “the real broader issue is of Freedhoff not liking criticism and not liking people saying that some EPA actions favored the interests of industry over communities.”

Documents published with this article:

Regulatory Capture of EPA’s Chemical Assessment Process

EPA’s Failure to Consider Toxicity of PCBTF

Modification of Scientific Data in the New Chemicals Division

Update: March 2, 2022

This article has been updated with comments from an environmental advocate who was present at the January meeting with Freedhoff and disputed her characterization of her comments.

This content originally appeared on The Intercept and was authored by Sharon Lerner.