According to former Defense Secretary Mark Esper, on June 1, 2020, a week after the murder of George Floyd, then-President Donald Trump asked him to deploy 10,000 active-duty troops to the streets of the nation’s capital and have them open fire on protesters. “Can’t you just shoot them?” Trump asked, in an Oval Office meeting Esper describes in the introduction to his new memoir. “Just shoot them in the legs or something?”

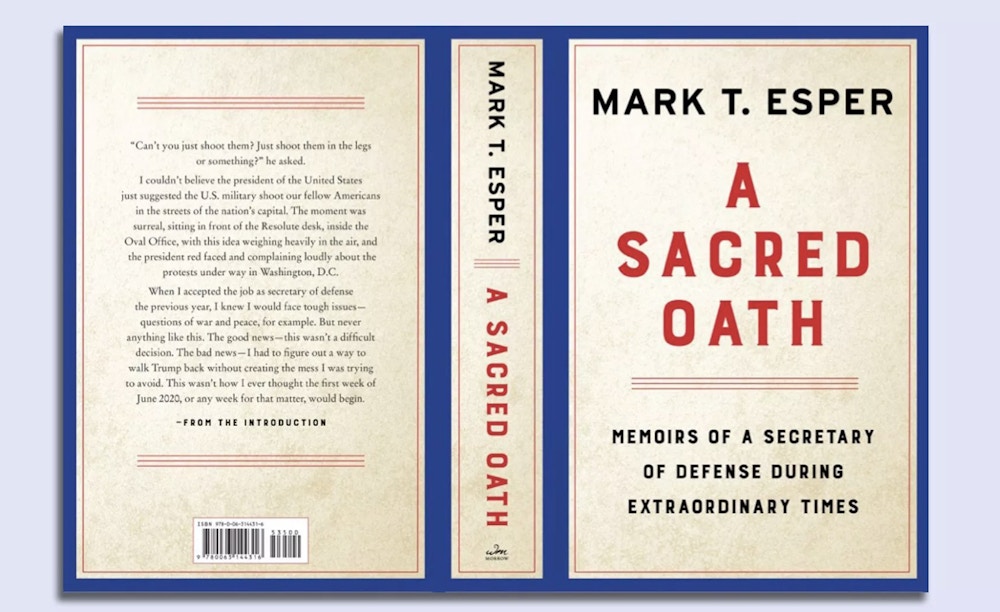

Esper, who waited nearly two years to reveal that an American president had urged him to launch a Tiananmen Square-style crackdown on dissent, is well aware that Trump’s plan was both illegal and immoral. That’s clear because his account of this “surreal” request is included not just in the introduction to his memoir, “A Sacred Oath,” but also featured on back cover of the book, due to be published next week.

But instead of immediately resigning and letting the American people know that their president was a danger to the republic, here is what Esper did that day: He tried to placate Trump and then joined the president in posing for photographs outside St. John’s Church, across Lafayette Square from the White House, after federal agents had used chemical irritants and force to violently disperse peaceful protesters from the square.

A month later, when Esper was called before the House Armed Services Committee to explain how the military had been used to suppress dissent that day — and that night, when Black Hawk and Lakota helicopters swooped low over protesters in Washington, D.C., using winds from the rotor wash to instill terror — the defense secretary made no mention of Trump’s request to use potentially deadly force.

In that hearing, Rep. Adam Smith, the Democratic chair of the House Armed Services Committee, asked Esper and Gen. Mark Milley, the chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, to describe “what sort of conversations went on between the Department of Defense and the president and others in the White House” about Trump’s public threat to use active-duty soldiers to clear the streets.

Instead of answering that question, Esper offered bland assurances that the military, including 43,000 Army and Air National Guard personnel deployed in 33 states and the District of Columbia during “the civil unrest” after Floyd’s murder, was committed to “remaining apolitical” and ensuring that “our fellow Americans have the ability to peacefully exercise their First Amendment rights.”

Esper — who said last year that he was writing his book because the “American people deserve a full and unvarnished accounting of our nation’s history, especially the more difficult periods” — told the New York Times this week that he had concluded that Trump “is an unprincipled person who, given his self-interest, should not be in the position of public service.”

Given that his firsthand experience of Trump led him to this view, it is important to ask why Esper chose not to reveal that the president he served had wanted to turn the military on the people when it might have made a real difference — either before the 2020 election, when it might have dented Trump’s chances of winning, or just after it, when Trump fired him and put loyalists in charge of the Pentagon before urging his own supporters to disrupt the certification of his loss.

And here, it must be said, there appears to be something even more troubling at work than just the fact that Esper might expect to sell more copies of his book by waiting to reveal the most damaging information about Trump — as former Trump aides John Bolton and Stephanie Grisham did before him.

What I’m thinking of is a disturbing deference to presidential authority that seems deeply rooted in Washington. There was clear evidence of that in something else that Smith said to Esper and Milley at the start of the July 9, 2020, hearing on the events of June 1 that year.

Before asking the top officials in the Pentagon to explain what role the military had been asked to play in the abusive policing of the racial justice protests, Smith told them that he was aware of “the difficult position that any secretary of defense and any chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff is in. You work for the president. He’s commander-in-chief.”

But given the gravity of what Esper knew about Trump’s desire to see American troops open fire on peaceful protesters, what he chose to conceal from Congress and the public is far more grave than the sort of policy disagreement that Smith described as routine.

And while other senior officials — including Trump’s first secretary of state, Rex Tillerson, his first secretary of defense, Jim Mattis, and his former chief of staff, John Kelly — let their dim views of the former president’s character and intellect trickle out through leaks to reporters like Bob Woodward, Esper sat on explosive evidence about Trump’s willingness to unleash a form of martial law even after he refused to accept the results of the 2020 election.

Looking at Esper’s silence until after Trump was out of office, we are left with a very strange definition of what it means to be a public servant — one who cannot be expected to tell the public that the president would have them shot.

This content originally appeared on The Intercept and was authored by Robert Mackey.

Robert Mackey | Radio Free (2022-05-06T20:52:42+00:00) Mark Esper Waited Two Years to Tell Us Trump Wanted Troops to Shoot George Floyd Protesters. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2022/05/06/mark-esper-waited-two-years-to-tell-us-trump-wanted-troops-to-shoot-george-floyd-protesters/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.