At a press conference during the Paris climate summit in 2015, when leaders from 196 countries had gathered to reach an agreement on how to slow climate change, President Barack Obama proposed a solution for their planetary problems: charge polluters for their greenhouse gas emissions.

“I have long believed that the most elegant way to drive innovation and to reduce carbon emissions is to put a price on it,” he said, speaking from a podium flanked with American flags.

Obama’s pitch was based on a cornerstone of American climate policy, the carbon tax. Championed by the likes of Bill Clinton, Senator Bernie Sanders, and some old-guard Republicans, and heralded by thousands of economists as essential in the fight against climate change, it would have imposed a fee on every ton of carbon released into the atmosphere, a cost that could spell the end of high-emitting industries like coal.

Although many environmentalists in Washington have spent the better part of two decades trying to pass a carbon tax in Congress, it was absent from the historic climate package signed by President Joe Biden last month. Instead of taxing polluters on their emissions, the Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA, aims to fight climate change with green tax credits for clean electricity and manufacturing, as well as for alternative-fuel and electric vehicles. These tax incentives are a major boon for developers of solar panels, wind farms, and other renewable energy technologies, companies expected to receive a combined $60 billion in tax benefits over the next decade. The law also incentives Americans to purchase more electric vehicles by offering a $7,500 tax credit to buyers of new EVs and $4,000 to buyers of used ones.

So how did the conversation shift so dramatically, from one focused on taxing polluters to one based on using the tax system to reward developers and buyers of renewable technologies? Is the dream of a nationwide carbon tax dead?

“It looks good as a model,” said David Hart, a senior fellow at the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation in Washington, D.C. “If you didn’t have politics, and you didn’t have emotions, and you didn’t have cultural biases in the activities impacted by these taxes, then it looks good on paper.”

The idea of putting a tax on carbon emerged at a time when scientists were beginning to reach consensus that the unabated burning of fossil fuels was changing the world’s climate. At an economics conference in 1981, Yale economist William Nordhaus presented a landmark paper that asked how economic policy could slow the buildup of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. He considered a range of available solutions, from energy conservation to investments in green technologies, but concluded that a tax on carbon was the most powerful mechanism for stopping climate change.

The reason, Nordhaus argued, had to do with the basic economic principle of supply and demand: If you want someone to do less of something, charge them for it. And because the dirtiest polluters would pay the most in taxes, they would likely be the first to shut down, decarbonizing the economy at the fastest rate.

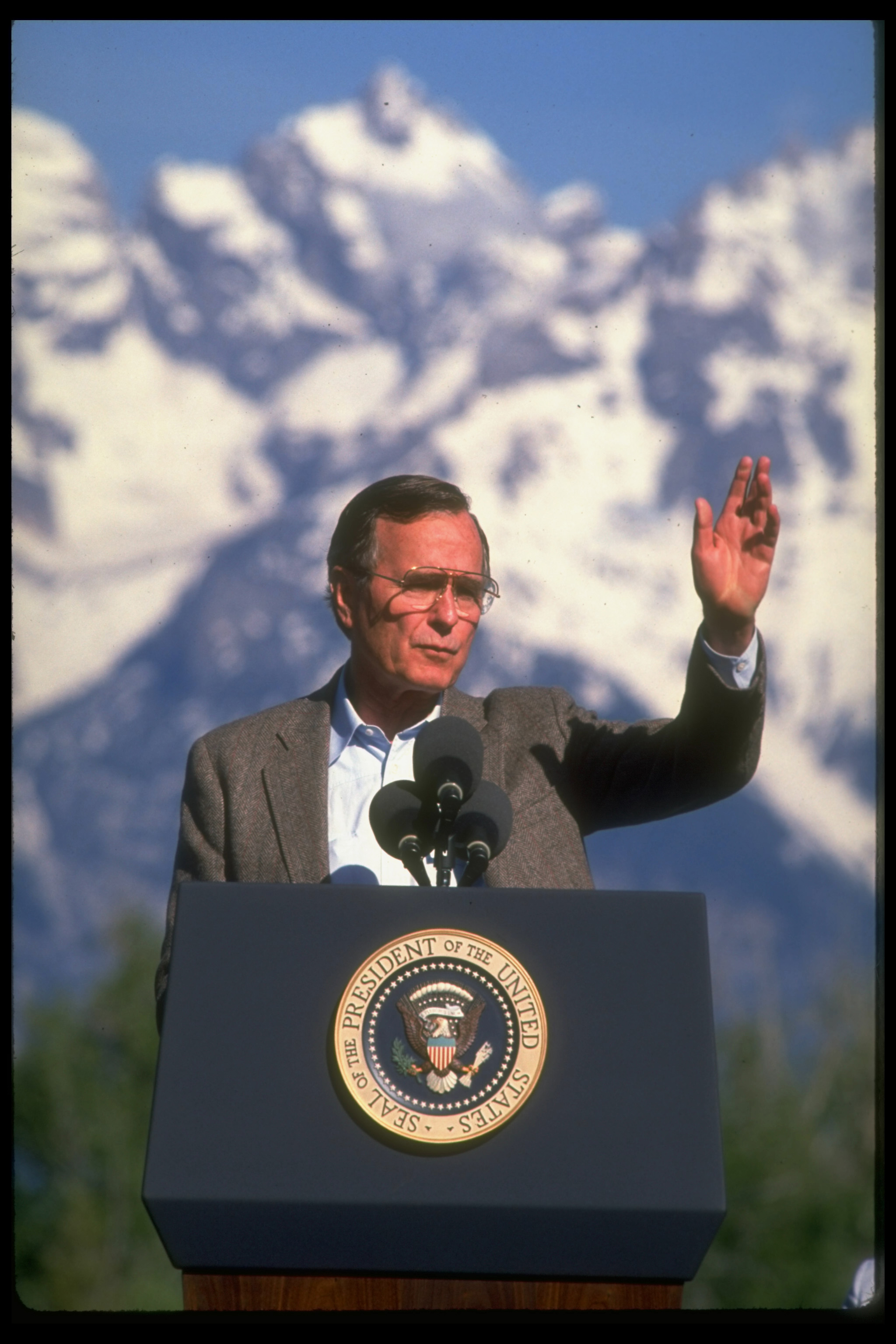

Proponents believed this strategy could gain bipartisan support since it relied on the market and not on government spending to get the job done. Back then, protecting the environment wasn’t such a polarizing issue. President Richard Nixon’s administration had established the Environmental Protection Agency and passed the Endangered Species Act. During the presidential election of 1988, Republican candidate George H. W. Bush proclaimed that issues related to the nation’s land, water, and soil “know no ideology, no political boundaries,” and pledged to fight climate change using the power of markets. He declared that he’d be “the environmental president.” Once in office, Bush overhauled the Clean Air Act with sweeping amendments to address ozone emissions, acid rain, and industrial pollution.

But in 1993, when President Clinton proposed a “BTU” tax, referring to a unit of heat, on coal, oil, and natural gas, he encountered major resistance from both sides of the aisle, and the bill tanked before it was ever put to a vote in the Senate. For the following decade and a half, Republicans had the majority in the House of Representatives, and conservative foundations pumped millions of dollars into moving the party toward climate denial. Then in 2009, two Democrats, Representatives Henry Waxman and Edward Markey, made a second attempt at passing a carbon-pricing bill, this time using a cap-and-trade approach. The strategy puts a limit on polluters’ carbon emissions, while enabling them to buy additional capacity from other companies that have not yet hit their cap. That bill also failed.

Support for a carbon tax became a political death knell, due in part to the power of the fossil fuel lobby: A 2019 study found that political lobbying reduced the chances of Waxman-Markey’s passing by 13 percent. In subsequent years, powerful lobbying groups helped to take down incumbent Republicans who advocated for climate legislation like Representative Bob Inglis, who was unseated from his South Carolina district in a 2010 primary after unabashedly supporting a carbon tax.

But industry influence and Republican objection alone cannot explain the policy’s undesirability. Even Democrats began to shy away from taxing carbon emissions in recent years. Senator Sanders called for a carbon tax as part of his platform in 2016, but gradually withdrew his support, and the tax was excluded from progressive Democrats’ flagship climate proposal, the Green New Deal.

Critics have pointed out that such a tax could be regressive, meaning that it would hit low-income families the hardest. Numerous studies have shown that recycling the tax revenue through the economy and giving it back as checks to low-income households balances out the burden, but the mechanics of this money-maneuvering are difficult to articulate, and the solution has not garnered much public support.

“A well designed carbon price, of course, can spur significant investments, good jobs, and redress structural injustices. But at the front end, it says, ‘We’re gonna raise prices, and then we’ll compensate you,’” said Ben Beachy, the vice president of manufacturing and industrial policy at the BlueGreen Alliance, an organization that conducts research about solutions to environmental challenges. “It’s little wonder that this [the IRA’s incentive package] is the approach that President Biden just signed into law.”

James Stock, a professor of political economy at the Harvard Kennedy School, agreed that a tax incentive program is more politically palatable than a carbon tax, but added that it has only recently become a viable climate policy.

“The world [today] is a very different one from the mid-2000s when the calls for a carbon tax were big,” said Stock. “Back then we didn’t have any good alternatives to reducing emissions other than using less.”

The Carter administration implemented the first solar power subsidies in the 1970s when the nation was reeling from an energy crisis that arose, in part, after the Arab states in OPEC instituted an oil embargo to protest U.S. support for Israel. But in the decades following their initial deployment, solar and wind power were still viewed as nascent technologies that could not compete with coal-fired power plants.

Today, solar power is less than one-fifth of the price that it was in 2009, and the cost of wind turbines has dropped by more than half over the same period. And while constructing solar farms used to be three times more expensive than building new coal plants, it’s now cheaper to build and operate a new solar farm than to run an existing coal-fired power plant.

As a renewables-heavy grid became more viable, so too did an investment-led climate policy, one based on incentives rather than penalties.

Over the past decade, organizations like the BlueGreen Alliance and the Environmental Defense Action Fund began building coalitions to create a unified vision for a climate policy that could succeed on Capitol Hill. These groups did not agree on everything (some, for example, supported emergent technologies like carbon capture while others preferred natural solutions like reforestation), but they shared the belief that shifting the economy away from fossil fuels required more government intervention, not less.

The birth of the Sunrise Movement, a national youth-led organization launched in 2017 to fight climate change, marked a turning point in the popularity of the strategy. The group emphasized the importance of what’s called a “just energy transition” from a fossil-fuel economy to a green one, a shift that would create thousands of jobs in the renewables sector and battle climate change alongside income inequality and environmental injustice. Many of the movement’s supporters, including Representatives Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Deb Haaland, won their seats in the 2018 midterm elections. The group heavily influenced the Green New Deal proposal, whose omission of a carbon tax helped to sour the policy among Democratic incumbents on the Hill.

“There is no doubt that the Sunrise Movement and their focus on the Green New Deal created energy for a massive expansion of this [incentives-first] strategy,” said Molly Prescott, a spokesperson for Senator Jeff Merkley, the Democrat from Oregon who helped push for the green tax incentives in the IRA’s failed predecessor, the Build Back Better Act. She added that the senator has supported a carbon tax in the past, but that “changing economies” as well as environmental justice advocacy groups had convinced him to focus on other climate policies in recent years.

“Twelve years ago, I watched my landmark climate legislation pass in the House and die in the Senate,” said Democratic Senator Ed Markey, one of the authors of the failed 2009 cap-and-trade bill. “I am grateful for the countless young people and all those in the climate movement who breathed new life into our fight for climate action.”

Still, the IRA’s incentives-first approach isn’t without its critics. Some experts believe that a climate policy that depends largely on subsidies with little penalty for polluters is insufficient. What is lost without a carbon tax, they argue, is economic efficiency. Since the IRA does not penalize polluters (with the exception of a fee on companies that exceed their allowable methane emissions), the dirtiest sources won’t necessarily be phased out the fastest.

To test this theory, researchers at University of California, Berkeley and the University of Chicago simulated a decarbonization of the electricity sector using a carbon tax in one case and green subsidies in another. The results were surprising: The two policies did not achieve substantially different fossil fuel reductions by the end of the decade.

But that doesn’t mean that the policies are equally effective. Severin Borenstein, a professor at Berkeley and one of the authors of the study, cautioned that what tax credits do for the electricity sector in terms of providing both innovation and efficient decarbonization may not hold true for other industries. In particular, he believes that green credits will not work as well to clean up transportation, which is responsible for the largest share of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions. That’s because the people likely to buy new electric cars have not been driving, on average, the dirtiest vehicles.

“They drive new cars, and they tend to be politically liberal, which tends to mean they don’t drive the biggest emitters,” he said. “And so in some ways, it’s just the opposite of the electricity sector where we said, ‘Look, the coal is gonna get pushed out first anyway.’ That is not true with EVs.”

Stock, the Harvard economist, acknowledged this dynamic, but added it should be balanced against the fact that when wealthy Americans buy new green technologies, they help drive down the prices for everyone else. This trend is playing out now in electric vehicles, with car manufacturers rolling out high-end electric versions first in order to finance the development of cheaper models.

“So Ford and Tesla learn to make the EVs, and then that creates the capacity to create cheaper versions for the mass market,” Stock said.

These trends not only help reduce America’s carbon footprint, but also the world’s, said David Hart, the senior fellow at the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation. Germany made a huge investment in solar power in the early 2000s, and “bought down the price” for the global market, he said, meaning that the country’s investment in solar eventually made it cheaper for everyone else. “As rich countries, that’s what we should be doing.”

Hart, along with many other policy experts, argues that the passage of the IRA does not necessarily mean a carbon tax is dead. Rather, the new legislation is just a first step in slashing the country’s carbon emissions and preventing the most disastrous consequences of climate change.

“I do think there are going to be places and times when it [the carbon tax] is going to be a crucial tool to get to the last mile, but I don’t think it should be a focus of policy,” Hart said. “The goal should be to develop these technologies with a direct funding approach. Let’s make the clean stuff cleaner and cheaper before you make the dirty stuff more expensive. That is the sort of guiding spirit [of the IRA] if you can discern one here.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline ‘Make the clean stuff cheaper’: Did the IRA kill the carbon tax? on Sep 6, 2022.

This content originally appeared on Grist and was authored by Lylla Younes.

Lylla Younes | Radio Free (2022-09-06T10:45:00+00:00) ‘Make the clean stuff cheaper’: Did the IRA kill the carbon tax? . Retrieved from https://grist.org/politics/did-biden-inflation-reduction-act-ira-kill-the-carbon-tax/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.