On September 9, with virtually no press coverage, President Biden sent an official letter 1 to Congress extending a state of emergency that was first declared in the aftermath of 9/11, more than two decades ago. "The terrorist threat ... continues," the letter declares. George W. Bush's original declaration of emergency led to trillions of dollars in military spending and the transformation of American society. Thousands of young Americans, and well over a million people in the Middle East, lost their lives.

Illness doesn't make for dramatic television the way terrorism does. Sick people suffer and die alone, far from the lights and cameras.

2,996 people died on 9/11. The enormity of the loss was almost too much bear. The reality of death was especially acute for me because, unlike most people, I had friends and acquaintances who died that day. Had I not changed jobs, I would have been working there myself. (I kept a photo-ID day pass to World Trade Center 2 for years before finally deciding that it was a fetish object which trivialized the tragedy.) My wife missed a breakfast meeting there that morning because she had the flu; she might have been among the victims. I don't need to be told how tragic that day was.

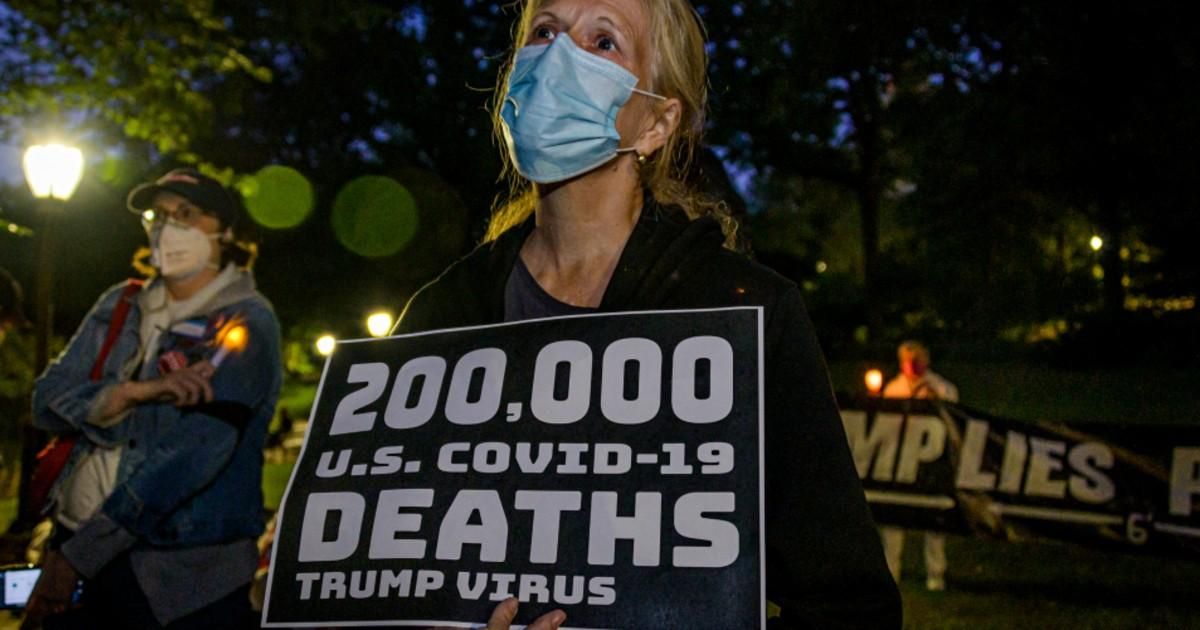

And yet, I wonder: why do some deaths matter so much more than others? More than one million people have died from Covid-19 in this country. Even in a "good" week like this one, the death average is 383 per day. That's roughly one 9/11 every week. But we're not spending trillions of dollars in response. The Administration's relatively modest budget request of $22 billion for Covid response is languishing in Congress—the same Congress that recently lavished much more than that, and much more than the Pentagon requested, onto an already bloated military budget. (More war funding 2 is almost certainly on its way.)

Why is a life taken by terrorism worth so much more than a life lost to Covid-19? Part of the answer must lie with the fact that illness doesn't make for dramatic television the way terrorism does. Sick people suffer and die alone, far from the lights and cameras. And sick people don't have lobbyists, while weapons manufacturers do. That's no excuse: Congress must act now to fund Covid care. If Republicans are blocking those funds, as seems to be the case 3 , Democrats must overcome their usual diffidence and confront them. (It's worth contacting your representative and senators about.)

The Administration isn't helping its own case, to put it mildly. Its communications on Covid are misleadingly upbeat, sucking the sense of urgency from the crisis. One White House communique 4 read, "This summer, we showed that we know how to manage fluctuations in COVID-19 and move forward safely." Safely? A review of the CDC's tracking data shows that more than 40,000 have Americans died of the disease since June 1, 2022. That may pale against the total toll of 1,045,000 (as of this writing), but it is a catastrophic number all the same.

Back in June, administration officials were quietly telling Politico 5 that 200 deaths per day—a horrifying number—would indicate that "the pandemic would be under control." That "aspirational" number, which was called "a general metric people have bounced around a lot" is a long way away, but in many ways the Administration is nonetheless declaring "mission accomplished."

The politics are obvious. The Democrats don't want to go into November's election with the perception that the pandemic is out of control. And, to be fair, they have requested the money. But Congress is showing no sign of coming through, and there seems to be a reluctance to demand it. Doing so might undermine the false sense of confidence that's being promoted.

Meanwhile, as Martha Lincoln and Anne N. Sosin report in The Nation 6 , "Coronavirus Response Coordinator Ashish Jha (has) announced that the federal government will end its expenditures for Covid vaccines, treatments, and tests this fall (and) the popular federal program that sent Americans free at-home Covid tests was then shuttered on September 2." Jha also said, "My hope is that in 2023, you're going to see the commercialization of all of these products."

It also reflects the profound indifference to suffering and death that characterizes our current system of privatized insurance.

One person's hope is another's fear. The commercialization of these products—many of which were developed at public expense—has already put many of them out of the reach of millions. And it's getting worse, not better. As Lincoln and Sosin write, "The United States will be among the first countries to cease the provision of free Covid vaccinations and treatments, leaving low-income people—a group that is overrepresented among the pandemic's victims—with even less protection." They also quote a health policy scholar as saying we will soon "enter a phase where we can virtually wipe out deaths among the well-insured."

Wiping out deaths among the well-insured. In a nation with 28 million uninsured and many millions more severely under-insured, that comment serves as a condemnation of public policy and state morality. It also reflects the profound indifference to suffering and death that characterizes our current system of privatized insurance. Only 12 percent of Americans think this "system" works very or extremely well, according to polling 7 , versus 56 percent with negative feelings (The positive thinkers are probably the people who haven't needed medical care yet.)

We should ensure that everyone is well-insured through a system of public health insurance. In the meantime, the very least the government can do is provide the funding and services needed to stem the ongoing wave of deaths from Covid-19.

"Never forget," they tell us about 9/11. But what are we supposed to remember, exactly? One would hope we're meant to remember the lives lost that day. But while we're called upon to remember that day's dead, people are dying all around us. They pass away, alone and forgotten, while the people's wealth flows into the machinery of war.

This content originally appeared on Common Dreams - Breaking News & Views for the Progressive Community 8 and was authored by Richard Eskow.