ANALYSIS: By Khairiah A. Rahman

“On the ground, there is a sense of disquiet and distrust of the organisers’ motivations for the hui, as some Muslim participants directly connected to the Christchurch tragedy were not invited.”

— Khairiah A. Rahman

The two-day Aotearoa New Zealand government He Whenua Taurikura Hui on Countering Terrorism and Violent Extremism this week saw participation of state agencies, NGOs, civil rights groups and minority representations from across the country.

Yet media reportage of deeply concerning issues that have marginalised and targeted minorities was severely limited on the grounds of media’s potential “inability to protect sensitive information”.

Lest we forget, the purpose of the Hui is a direct outcome of the Royal Commission recommendations following the 2019 Christchurch mosque attacks.

- READ MORE: Shifting the dynamics in popular culture on Islamophobic media narratives — Pacific Journalism Review

- Mediawatch: Hui over Christchurch terror attacks puts media under the spotlight

- NZ communities gather in unity for He Whenua Taurikura Hui on countering violent extremism

- Community groups urge need to combat online hate speech at second counter-terrorism hui

- Other countering terrorism reports

The first hui last year had a media panel where Islamophobia in New Zealand and global media was addressed, and local legacy media reiterated their pact to report from a responsible perspective.

A year later, it would be good to hear what local media have done to ask the hard questions — where are we now in terms of healing for the Muslim communities? What is the situation with crime against Muslims across the country? What projects are ongoing to build social cohesion for a peaceful Aotearoa?

This year, the organisers decided to have the Hui address “all-of-society approaches” to countering violent extremism. This means removing the focus on issues faced by Muslims and extending this to concerns of other minorities subjected to abuse and hate-motivated attacks.

While Muslim participants embraced sharing the space with disenfranchised communities, many reflected that this should not detract from a follow-up to issues discussed at the last hui.

A media panel should address the role of media in representing the voiceless communities. In addition to media following up on Islamophobia, how has media represented minority groups based on their ethnicity, faith or sexual orientation? How can media play a direct role in truth-telling that would inspire social cohesion?

A participant of the LGBTQ+ community shared how bisexual members were threatened on social media as a result of local and international media’s reportage of the Amber Heard misogyny case in the US and the negative representation of bisexual people.

As a social conduit for communal voices and public opinion, the media have a significant role in countering terrorism and violent extremism and should not be excluded from the difficult conversations. Legacy, ethnic and diversity media must be included in all future hui, regardless of topics.

Confidential information can be struck from the record if necessary, but often this is hardly shared in a public forum.

There is little point having a Hui where critical national issues of safety and security are discussed across affected communities, if they are just noise in an echo chamber for those affected while people that care outside of this room are unaware.

Six takeaways from the Hui

Discussions centred on what community groups have been doing on the ground and what the larger society and government must do to counter radicalisation and terrorism.

- Victims’ families call for a Unity Week

Hamimah Ahmat, widow of Zekeriya Tuyan who was killed in the terror attack, and who is chair of the Sakinah Trust, called on the government to observe an official Unity Week for the country to remember the 51 lives lost in Christchurch.

“More than funds — we need to make sure that the nation ring fences their time for reflection and their commitment to that [social cohesion].”

Sakinah Trust, formed by women relatives of the victims, organised Unity Week where Cantabrians participated in social activities and shared social media messages on “unity” to commemorate the lives lost and build a sense of togetherness across diverse communities.

This bonding exercise connected more than 310,000 New Zealanders and initiated 25,000 social media engagements. Hamimah emphasised the importance of this as during the pandemic Chinese migrants had suffered racism and hate rhetoric.

“We need a National Unity Week not just because of March 15 but because it is an essential element for our existence and the survival of our next generation — a generation who feels they belong and are empowered to advocate for each other,” she said.

“And this is how you honour all those beautiful souls and beautiful lives that we have lost through racism, extremism and everything that is evil.”

2. Issues and disappointment

Members of the IWCNZ (Islamic Council of Women in New Zealand) and other ethnic minority groups have repeatedly shared their disappointment that some speakers appeared to equate the terrorist mass murder in the two Christchurch mosques to the LynnMall attack in Auckland. Yet, the difference is stark.

One terrorist was killed and the other was apprehended unharmed. One had a history of trauma and mental instability, and police knew of this but failed to intervene.

The other was a white supremacist radical who had easy access to a semi-automatic weapon. While both could have been prevented, the LynnMall violent extremism was within the authority’s immediate control.

Aliya Danzeisen, a founding member of Islamic Women’s Council of New Zealand (IWCNZ), said it was offensive that there was an inappropriate focus on the Muslim community in discourse on the LynnMall attack as there was failed deradicalization by the government corrections department.

“We find it offensive as a community because it was a failed government action, not getting in front, again, that someone was shot and killed and seven people were stabbed.”

Danzeisen also reported that despite sitting in the corrections forum for community, she was unaware of any change since the Royal Commission in terms of addressing radicalisation.

On the ground, there is a sense of disquiet and distrust of the organisers’ motivations for the hui, as some Muslim participants directly connected to the Christchurch tragedy were not invited.

Murray Stirling, treasurer of An Noor Mosque, and Anthony Green, a spokesperson for the Christchurch victims, were present at last year’s Hui but did not receive invitations this year.

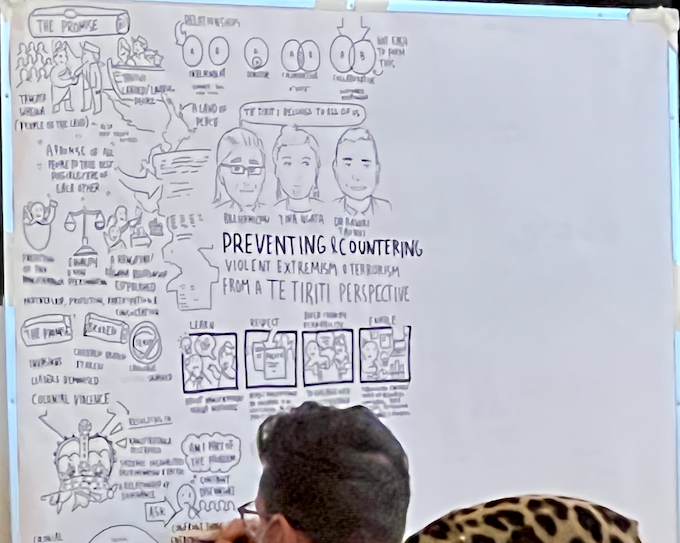

3. Academic input from Te Tiriti perspectives

The opening of the conference was led by research from a Te Tiriti perspective. The Muslim community had called for a Te Tiriti involvement in the Hui to acknowledge the first marginalised people of the land.

One shared feature of all the discussions related to colonialism. Tina Ngata, environmental, indigenous and human rights activist, called out those in power who passively protect and maintain colonial privilege, allowing extreme and racist ideas to persist.

Ngata cited racialised myth-making in media and schools, state-sanctioned police violence, hyper-surveillance and the incarceration of non-white people.

She argued that a critical mass of harmful ideas was growing and that it is the “responsibility of accountable power to engage humbly in discussion; not just about participants as victims or solution-bearers but also about structural power as part of the problem”.

Bill Hamilton from the Iwi Chairs forum paid tribute to the work of the late Moana Jackson in the area of Te Tiriti, reminding people that Te Tiriti belonged to everyone.

Hamilton recounted that despite Te Tiriti’s promise of protection and non-discrimination, Māori suffered terrorist acts.

“We had invasions at Parihaka . . . our leaders were demonised . . . our grandparents were beaten as small kids by the state for speaking their language [Māori].”

Hamilton reflected on the values of rangatiratanga and said that perhaps, instead of forming a relationship with “the crown”, Māori was better off forming relationships with minority communities based on shared values.

He explained that rangatiratanga is a right to self-determination; the right to maintain and strengthen institutions and representations. It is a right enjoyed by everyone.

Hamilton called for a state apology and acknowledgement of the terrorism inflicted on whānau in Aotearoa. He proposed a revitalisation of rangatiratanga, the removal of inequalities and discrimination, and the strengthening of relationships.

Rawiri Taonui, an independent researcher, presented a Te Tiriti framework for national security.

There was a marked difference between the Crown’s sovereign view of the Te Tiriti relationship with Māori and Māori’s view of an equal and reciprocal Te Tiriti relationship with the Crown.

Taonui highlighted that while Te Tiriti was identified as important for social cohesion in the Royal Commission Report, Te Tiriti was absent in the 15 recommendations for social cohesion.

He explained the tendency in policy documents to separate Māori from new cultural communities.

“That is a very unhelpful disconnect because if we are trying to improve social cohesion, one of the things we need to do is bring Māori and many of our new cultural communities together. Because we share similar histories — colonisation, racism, violence.”

Taonui proposed a “whole of New Zealand approach” towards countering terrorism, emphasising social cohesion to prevent extremism as “we all belong here”.

4. On countering radicalism

In a panel session on “Responding to the changing threat environment in Aotearoa”, Paul Spoonley, co-director of He Whenua Taurikura National Centre of Research Excellence, said that he was confused about how communities should be engaged as “often the affected communities are not the ones that provided the activists or the extremists. How do we reach out to those communities who might often be Pākehā?

“By the time we get to know about these groups, they have progressed down quite a long path towards radicalisation.

“So if we are going to provide tools to communities, we must understand that the context in which people get recruited are often very intimate; we are talking about whānau and peer groups. We are talking about micro settings.”

Sara Salman, from Victoria University in Wellington, spoke on radicalism and the thought processes and emotional attraction to notoriety and camaraderie that encourage destructive behaviours.

For radicals, there is a feeling of deprivation, “a resentment and hostility towards changes in the social world”, whether these are women in the workspace, migrants in society, or co-governance in the political system.

In the context of March 15, the radical is typically a white supremacist male. Such males join extremist groups because they feel a sense of loss and are motivated by power and social status.

According to Salman, there is now a real threat to our governance and democracy by radical groups through subtle ways like entering into politics.

“Radical individuals who ascribe to supremacy ideas are engaging in disruptions that are considered legitimate by entering into local politics to disrupt governance.”

Salman warned that although the government might prefer disengagement, which is intervention before a person commits violence, deradicalisation is critical as it aims to change destructive thinking.

Research showed that children as young as 11 have been recruited and influenced by radical ideas. Without being repressive, the government needs to deradicalise vulnerable groups.

5. Vulnerable communities and post-colonial Te Tiriti human rights

Several speakers on the “countering messages of hate” panel discussed horrific stories of physical, verbal and sexual attacks based on their identities including, ethnicity, disability and sexual orientation.

Many spoke about the lack of fair representations in media and professional roles and one participant emphasised that members of a group are diverse and not defined by stereotypes.

In an earlier session, chair of the Rainbow New Zealand Charitable Trust, called on society, including the ethnic and religious communities, to find ways of helping this group feel supported and loved in their communities.

Lexie Matheson, representing the trans community, spoke on the importance of being included in discussions about her people. She echoed my point at last year’s media panel about fair representations: “Nothing about us, without us”.

In the closing session, Paul Hunt, chair of the Human Rights Commission argued that the wide spectrum of human rights is normative as it defined the ethical and legal codes for conduct of states and constituted humanity’s response to countering terrorism.

Hunt offered a post-colonial human rights perspective and called for a process of truth-telling and peaceful reconciliation which respects the universal declaration of human rights and Te Tiriti.

“My point is in today’s Aotearoa, violent extremism includes racism, Islamophobia, antisemitism, homophobia, misogyny, xenophobia and white supremacy. And it is dangerous for all communities and for all of us.

“And if we are to address with integrity today’s violence, racism and white supremacy, we have to acknowledge yesterday’s violence, racism and white supremacy which was part of the social fabric of the imperial project in Aotearoa.”

6. What the Hui got right and wrong

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s presence and participation on the final day was timely, inspired confidence and implied a seriousness to address issues. Ardern covered developments that impact on national security, from technology, covid-19 and the war in Ukraine to climate change.

She addressed the radicalisation prevention framework and announced its release at year end, with an approved budget funding for $3.8 million to counter terrorism and violent extremism.

The Hui must have cost a pretty penny. Participants appreciated the food and comfort of the venue, but was there really a need for illustrators to capture the meetings on noticeboards?

If the organisers meant to enthuse participants with the novelties of artwork, stylish pens, and a supportive environment of aroha and healing, they have done a decent job.

But repeated feedback from Muslim representatives on the lack of action by government departments must be taken seriously and addressed promptly. All the good intentions without action achieve nothing.

Until those directly involved in the horrendous Christchurch massacres witness concrete sustainable actions that can support social cohesion, counter radicalism and violent extremism, the great expenses and show of love at this Hui would be wasted.

Khairiah A Rahman was a speaker at the media panel at the He Whenua Taurikura Hui in 2021. She is a senior lecturer at AUT’s School of Communication Studies, a member of FIANZ Think Tank, secretary of media education for Asian Congress of Media and Communication (ACMC), secretary of the Asia Pacific Media Network (APMN), assistant editor of Pacific Journalism Review and a member of AUT’s Diversity Caucus.

This content originally appeared on Asia Pacific Report and was authored by APR editor.

APR editor | Radio Free (2022-11-04T02:13:16+00:00) Countering terrorism hui in Aotearoa – vital but why marginalise media?. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2022/11/04/countering-terrorism-hui-in-aotearoa-vital-but-why-marginalise-media/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.