In honor of this beautiful publication, which is loosely concerned with the conditions of creativity, I thought I’d write something about what it’s like to be a creative person throughout one’s entire life. Creativity is always something I am thinking about. But what does it mean to be creative with my adolescent dreams now so far away in the rear-view mirror? I am excited by this question.

Last winter I saw a movie called Suspiria (the new version). It had a profound effect on me, and the ways I am thinking of my life as a creative person moving forward. For a while now, maybe five years or more, I have been living in a fog. A clouded and occluded mental state where not all of my ideas have been brought free.

I don’t think I fully realized how deep my brain had gone under until now. But maybe that has been due to time. There is, as they say, not enough of it. Right now I am taking the time to write down these words to you, for better or for worse. The wide open space where I can say (almost) anything at all—that sense of endless time—is what people might need to be creative.

Or maybe these past few years my brain has been sitting with its covering on due to biological things, a lot of weird health issues, and a submerging of my real self into caretaking. (But no, I don’t think it has been any of these things really, even if I might sometimes say that to comfort myself.) What is the real self? Spirits do not die, but selves can. Why are they here and why are they us? Is there any purpose to any of this, at all?

No, maybe the thick sheen of mud over what my spirit once made into words has had to do with my mental stability. A deep fear of the idea that nihilism is the only answer, or that the world wants us to think so, at least. It’s hard these days to not feel like the world doesn’t just want all of us completely gone.

Or maybe my fog has been because of the dark dead feeling of not feeling like anything I did really mattered, let alone anything I made. Who does and does not feel this way? For a seeming eternity, it has felt like writing poetry or making art is something I should not feel compelled to do, as it has no relevance to what really matters about life.

For better or for worse, I still think of the sublime. No matter what, it calls to me. That uncanny essence of being. No matter the erasure of time and existence, nor beauty, romance, an excess, the yellow light through the green in the window—all of it—I think being compelled to seek out the sublime is something real in this life to do.

But wait, have you seen the new Suspiria? If you haven’t seen it, then maybe you should soon. I suppose the movie is kind of sad and horrible, and maybe that’s not for you. It’s also maybe gratuitously full of blood and gore, although I don’t think so. It’s all just some cosmetics—the red paint and all the stuff of the horror genre. To me, the movie is about the triumph of the creative spirit, and almost nothing else.

If you have seen the movie (or maybe the older version of it), then you know that it’s about a coven of witches who are also dancers. They invite younger witches in to join them, only to kill them and make offerings to their great goddess, who is a demon. She is called the Mother Markos.

In the newer version of the movie, there is a younger witch (played by Melanie Griffith’s daughter, Dakota Johnson) whose name is Susie Bannion. Susie is a Mennonite who feels compelled to move to Berlin to become a dancer. She is the underdog, the beginner in the troupe of dancing witches, but—spoiler alert!—in the newer version of the movie, she rises up in the end and kills the whole coven. She does this because she is actually the greatest demoness of all. In the end, she says, “I am she,” and everyone who has forsaken her dies in a great cascade of red.

The fact of this great revenge—that the narrative allows her to twist everything in order to kill her enemies—means everything about what it means to be creative.

Through her art, which is part otherworldly dancing and part expert manipulation, she fools everyone in the coven. Of course, when she came there as a new dancer, they believed they had discovered her, and that by their own free will they had brought her into their world to be the vessel of an old reigning demon queen, who needed to be reborn into a young body.

Instead, Susie Bannion fools them all when she says, I am she! That great demon you speak of! It’s a moment of ultimate triumph. For anyone who has felt that people have plotted to silence you, manipulate you, or even kill you, this is the moment that you live for.

I feel pulled to this movie because I am some sort of artist (being a poet and a dancer aren’t so different), but also because of an ancestral tie. The movie is set in Germany, with the backdrop of the atrocities of the Holocaust being evident. After trying my best to hide my ancestry out of fear of being persecuted like my relatives before me, the movie pulls me into a landscape where so much horror has been done to them, and where I can hide no longer. There is poetic poignancy always in this sort of familial connection.

But there is a universal sort of individualism at play, too, when I think about this movie’s role as a source of inspiration. After seeing this movie, I felt triumphant. Perhaps this is what I have felt my whole life while writing a poem. I am she! Yes, that is what it feels like to write a real poem.

When I got home from the movie, I wrote the following poem in my triumphant glaze, partially or wholly occluded half-brain peeking out from behind the opening. Here it is:

Creativity as the Answer to the Question of Hate

No matter what they do

Choose Creativity as a lifestyle despite the horror

Yeah, I’m advocating for a no-holds-barred

Orgiastic connection with the divine

Through a belief that time and space

Are part of the whole construct that makes us unhappy

And while inviting in past and living principles

Of what you once were and what you will be

Because what you are now is an illusion

And as soon as you know that

You will rise up impersonal

In personal, private, and public ecstasy

An endless purple flower

In the midst of a perpetual purple rain

I’m saying hate has no place

In the house you will continue to make

With friends and lovers who in spite of the enemy

Show you that only love really is real

So do not go into the showers and stalls

My ancestors and children

Make the forest haunted with the Mars Yellow lights

You have strung up on the inside

Make the heart your place of worship

Be free

I am not sure if the poem is a “good” poem (I am not sure that I believe in that anyway), but it felt important to write it down. But then I thought, as I often do after writing poems, what’s the point of all of this anyway? The last few years, with our world in a top-heavy spin of evil, violence, and hate—and with the planet dying—it has been hard to take writing little lines on a screen too seriously. I think the movie put a swirl on me about witches, creativity, visual aesthetics, and other things that feel hard to take seriously in the space of the evil of our present moment. These are topics that I think about a lot (witches maybe the very least of them). But they are all topics, which for me flow together into one. Are they important? My answer lately has been no.

As I said earlier, when the Susie Bannion character says “I am she,” a mud demon crawls up from the bottom of the earth and kills everyone who has forsaken her. It’s as if the woman Susie was before this moment split, and in this demonic multiplication, a real sense of her was animated. Perhaps anyone interested in demonology might say that this is just what happens whenever demons are involved. But I think that this bifurcation is what happens anytime the sound of poetry is frayed. It’s the moment when Susie realizes who she is, that she was destined always to be a dancer, a witch, one of the three great mothers of the underworld, Mother Suspiriorum herself. I am she!

When one is creative they feel a magnetic sense of what they must do. Creativity theorists call this intrinsic motivation. Likely one day biochemists will pinpoint the exact formula that makes us motivated to make new things in order to enhance or de-enhance this drive (if they haven’t already), and after they bottle it and give it an exorbitant price, we will give it to children freely like all of the other drugs we push on them, such as iron and Vitamin D.

But when one knows who they are, that “they’ve always been the caretaker,” they become so close to the source of themselves that they split from the very thing they think up until that point. Perhaps this is like the way the spirit splits from the body in the moment of death, but more generative than that. It is a touching of the boundary of all things within the gyre.

Many years ago, I became obsessed with the idea of everyday creativity, or “small c” creativity. “Small c” is differentiated from “large C” Creativity as the difference between creativity that only affects a person and creativity that influences a field or domain. Of course, between the two is a whole world of making new things. “Small c” creativity is the idea that any person has creativity within them, and that the experiences of the world make these new leaps come out. But what affects the person affects the world, too, just not always on the same scale. Frankly, the essence of everyday creativity is also the true essence of witchcraft.

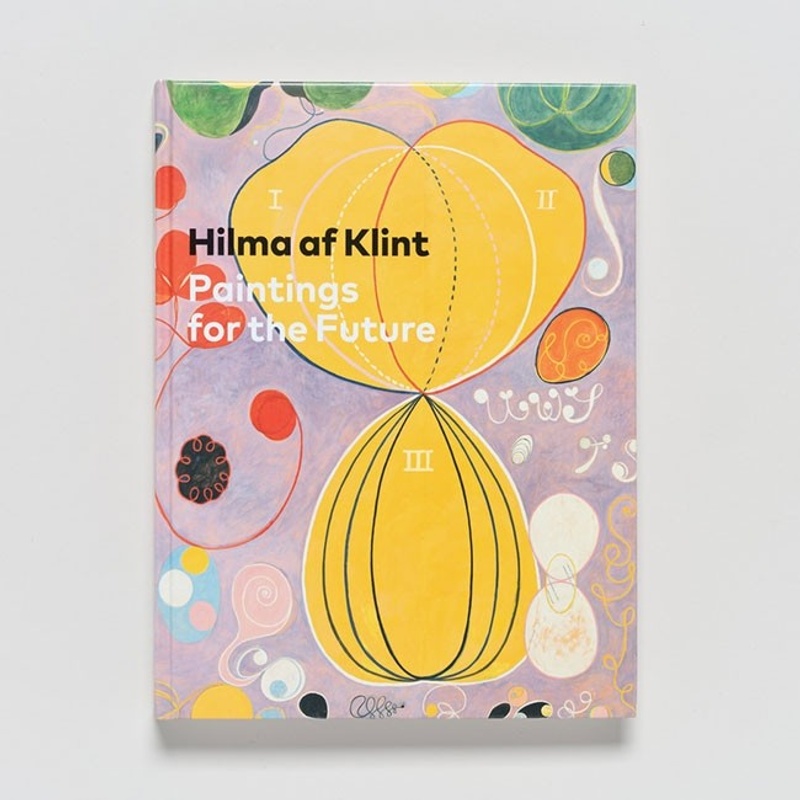

Like many other people, this spring I saw the Guggenheim show, Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future. Hilma af Klint knew and didn’t know who she was. She had an inkling. She was she. Perhaps the spirit of things that split from her in her paintings was already part of her, a possessed essence. Or perhaps it took time—because making a thing is not about solving it all in one piece. It’s about setting on a path of forgiveness for an eternity, for a time past your own.

In a world that is seemingly now devoid of a true ethical sense, there are ethical implications to doing creative work on the scale of the everyday. There always has been, but particularly now. Justice involves the belief that everything deserves a life of dignity, and a life of dignity includes the space to create within each day. The ability to find the mother who sees our need and doesn’t walk away in the space of the everyday, in the space of the word. Because a mother, whether Mother Suspiriorum, Mother Markos, or a mother walking a baby carriage with its sick baby, is the thing that doesn’t walk away. She comes to you when you call and call. She rises up from the earth when you say who you are, to be the essence of yourself. That is your guide.

My brain feels free and clear now. It won’t forever. In 40 years or less, it will be dust, floating free in the air and unable to connect together the imagery it now holds dear. I feel so real when I am being creative. I want everyone to feel this way, too. This is part of a just earth, an earth with dignity. It is a pressurized push past the ultimate darkness.

In the very end of Suspiria, there is a tree where two lovers had once carved their initials at the peak of their love. As the last scene of the movie fades, so too do their initials on the tree, as the sun blasts them away over time. In the background of the tree are a new set of concerns of other living humans—people carrying their children into their house. Although this is horribly sad, as one cannot help but think of their own youthful proclamations of true love, all being blasted away by the cruelty of time, it is hopeful, too. It suggests that the generative nature of things—for better or for worse—will save us all.

This world is cruel and probably always will be. When someone makes you feel not worthy, please remember that you are. You are an artist and it’s your job to do the thing that they are scared to do. When they tell you to slow down, to stop buying so many books and art supplies, to stop making things or to make sure every word you say is perfection, when they criticize what you are doing with acid frothing in their lungs, remember the sun blasts everything away. Including you. Including them. So you might as well just keep going until you can’t do it anymore.

Instead of being sad, when I think of that tree from the movie now, I think of the eternal goal of art. A one-true-love of existence. A tree where you carve and carve words, and don’t worry about the outcome. No great halls of literature, no great monuments to house your paintings. No sculpture bed to place your well-carved marble. No, the hallows of the underworld will house our work. And so be it.

I am she!

This content originally appeared on The Creative Independent and was authored by Dorothea Lasky.