What do you tell students?

Stick to what you believe in because you’ll be just as wrong as everyone else.

How did you develop that distinctive face that you draw?

It’s like asking someone who’s in deep water how they learned how to swim. Immediately, is the answer. Which is why they’re there to tell you about it. And that’s the way I’ve lived. I’m not a long-term planner.

How do you maintain a funny mood when it’s also work?

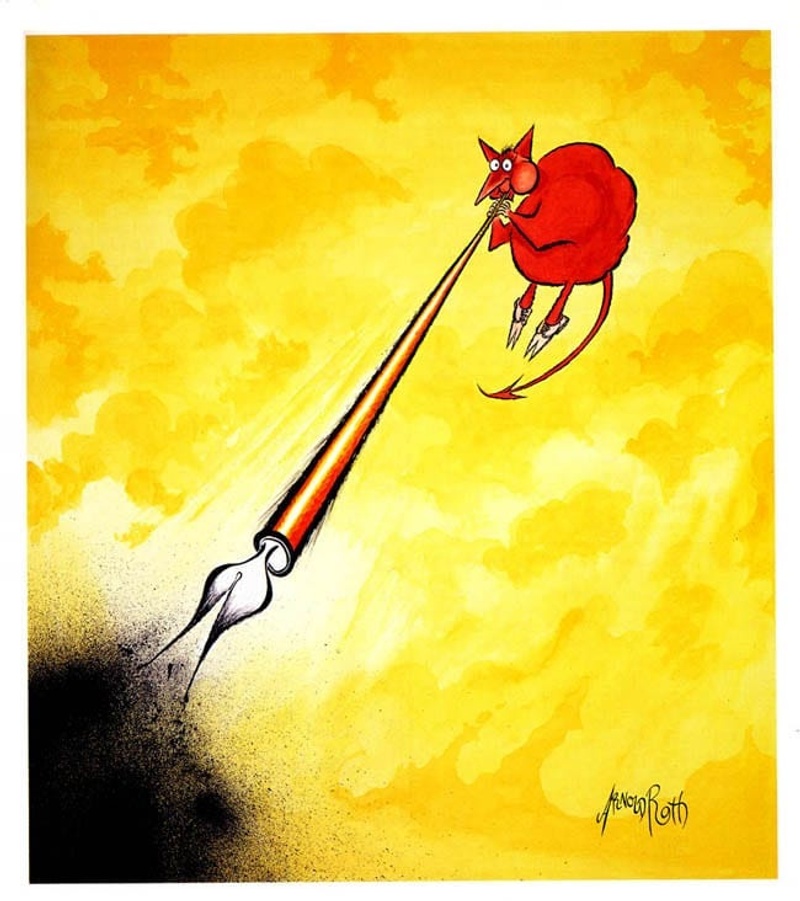

Well, that’s been tested, the way I react or anyone would. You just have to get control of yourself and know what the work needs. And that starts telling you all the answers. Not out loud, but you jump into that seat and open the ink bottle, and try not to spill it, like everyone else does. And dip your best points in the ink and get started.

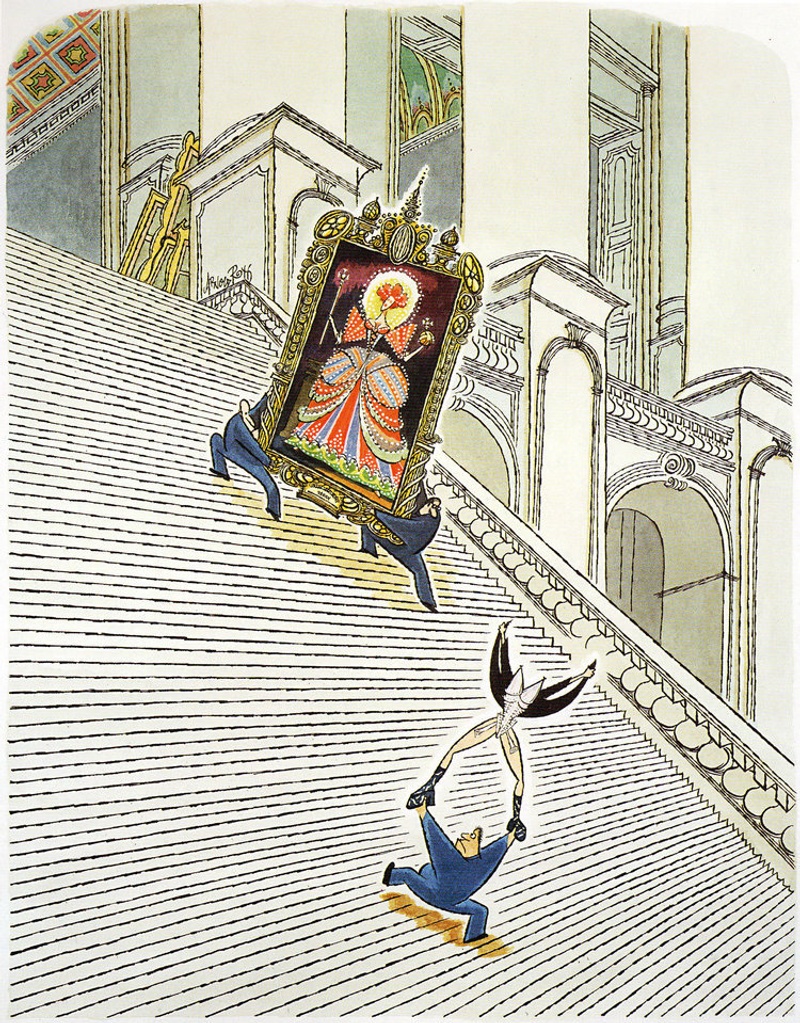

A lot of things will always be in everything that you do. I think this is true of writers, painters. Sometimes I would get an actual story or script. With Punch Magazine, I did whatever I wanted, about eight double-page spreads every year. We lived in England for a while. I had a lot of respect for Punch. It’s a lot older than I am, believe it or not.

I believe it.

I did one “Letter from America” a month for Punch, which was a weekly. For almost 30 years. They were always a pleasure to work with.

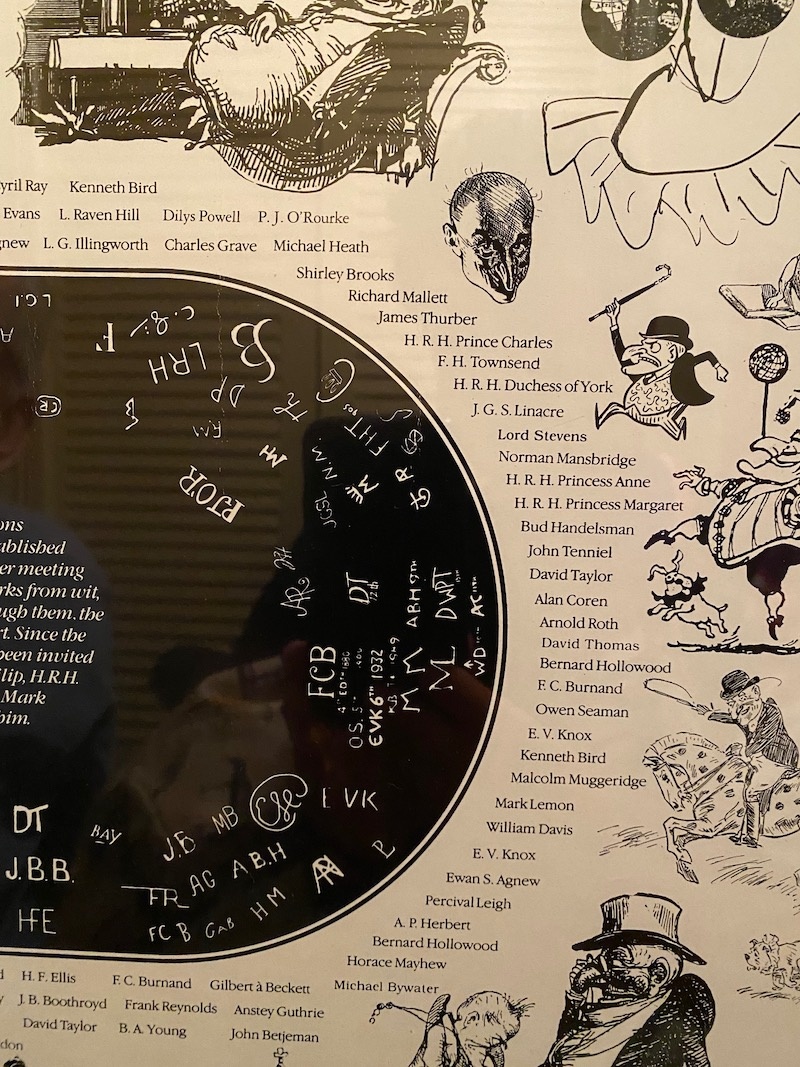

Oh. And I’ll show you something I’m very proud of. To have carved your initials in the same table as Mark Twain. And all those English writers. Ronald Searle, A.A. Milne. Like everyone else, I like to think I’m not prideful, but this is one thing I’m very proud of.

Can you talk about finding a line between being respectful but guarding your autonomy at the same time?

In a lot of cases, I was doing the drawing and thinking of the idea. And that was the fun of doing this sort of work. Your mind could play around with everything. And then if the worst happened, you snuck through the last chink in the door right before it got slammed in your face.

A lot of the fun in it was conceiving. When an art director asked to change something, I would say, “I’ll just draw another picture.” I didn’t like to redo work. A lot of art directors and editors think that they exist to make everybody redo some pieces of work. And I figured we were all professionals and we knew what we were doing. And just a matter of respecting each other.

But we all make mistakes too, and we have weaker and stronger works. But I thought the whole thing is fun. I still felt like I was back in school. And while, A, I didn’t have to pay attention to the teacher because I wasn’t going to learn anything. And B, I could go on with the drawings I was doing, with lots of paper and pencils and pens.

Can you tell me about when an art director is helpful, and the role that they play, and how maybe they have benefited your process in the past?

Oh, sure. I think the most important thing that they do, and there are always exceptions to these things, but, is their choice of which artist they should use for the piece.

So it’s like a director casting a film.

Yes. I think there’s a feeling that is involved in all this stuff. And that there are, as with artists, there are art directors who have better feelings, or more sensible feelings, in lots of cases, than others. But knowing the business and how humanity operates, who knows why who’s doing what? And that’s always an element in it.

Sports Illustrated used to send me to the West Coast, all around. And I’d always enjoy the trips. If they weren’t too long. And the exercise of it, too. You know, meeting people, talking to them. When you got to El Paso, wherever you were.

And the art director was very sympathetic. Richard Gangel. Say an important game was coming up next week. They’ll be writing about it, but there’s no picture because it hasn’t happened yet. So they would like cartoon art for that. So they would send me to the playoffs. And they’d say, “Two full-color pages. They’re due next week.” That was all they would say. They just gave you total freedom. They often had me write the piece as well. They would go on as long as five pages, where I would write and draw the pictures. And they paid very, very, very well.

My editor had been a World War II pilot in a small machine gun plane. He died quite a while ago now.

They were a very good company, Time/Life. They didn’t try to jump on your toes when you were trying to dance. Let me put it that way. And of course, it makes it more enjoyable the more open it is.

I want to hear about your grandma’s candy shop.

Well, you know how a candy store would have a big sheet window. And what they had in those days, this is the 1930s, there were old fashioned phones, where you held one piece at your ear and you spoke into the machine itself. And there were booths. Such things still exist, but, in drawing they would look different. They served sodas, beer, ice cream. And had a counter, but they also had tables. And a stamped metal ceiling. It was perfect. And they had about four to six phone booths. Wooden. You sat inside. Well, they make them the same way now actually. But you had a door, you closed the door and nobody in the store would hear what you were saying. Unless you were shouting your head off.

I do that on the phone sometimes.

This is around 1936, 37. I was a kid. And people would call the store, you know, call these phones. And we wouldn’t hang up. I was told to run up to so-and-so’s address, with the name, and I would tell them that they had a phone call. And they would, from two blocks away, come running down and run right into the store, and then get into the phone booth. They were happy. And they would give me a nickel or a dime which was bread in those days.

And everybody was happy. They had their phone call. There was a door on the booth, and there was a seat in there. You could sit down and close your door and go on forever. As long as you had dimes and nicks to keep it going.

Outside the candy shop, where was the next phone?

A block away. There was another candy store.

So each candy shop has a two-block radius of homes.

Yeah. But it wasn’t a very fancy candy shop. It had stools at the counter where you would have your ice cream, and it had bent iron furniture, so it could be used outside, I guess. And tables. And there would be six seats to a table.

It was great. It was both because your job was to run and ring their bell in their house. And in Philadelphia, it was a neighborhood, it was all families in the houses. Every now and then people rented a room there. It was a boarding house. They would always give you a few cents or a nickel at the most for coming to get them. I was getting rich.

Do you remember where the candy shop was, the street?

Yes. It was at Marshall and Montgomery. And there was a trolley line. Trolley cars were big in Philly. And the rails came along and they twist and turn through the neighborhood. There was a huge Stetson hat factory not far away. Many of the people who worked there would get off the trolley car and walk to where the factory was. They had a lot of employees. That, with all the locals who lived around there, where the store was, supported it very well.

When everyone wore Stetsons. They needed a lot of hats back then.

My youngest brother and my only sister–they’re twins–they were born at the Stetson hospital. They had so many employees and such a huge operation there.

Did your parents work for Stetson, too?

No, no. My father worked in a wholesale cut flower. They sold the flowers to people who ran shops. The top one in Philly.

My family name was Rothstein. When my father applied for the job, he got in this long line for this very big company. Well, you learn when you’re in waiting those lines, and you can see what the guy throws away, the guy who’s writing down everybody’s information, their name and how you can call them or write to them. And the Jewish guys would come back.

Of course, as soon as the person writing your name, as soon as they heard a Jewish name, that company didn’t want a lot of Jewish people working for them. And so they’d just bunch up the piece of paper and tell the kid, thank you, we’ll let you know.

Well, the story is when my father Louie got to the line, to his turn, he said his name was Louie Roth. They hired him. He was the only Jew who ever worked for that company. I guess they figured it was German or something.

Were you drawing on the tables of your grandma’s candy shop?

I drew everywhere. Just constantly drawing. I still do to this day. I love to draw. And I find myself scribbling. But it’s a lot of fun. And of course as I came along, it was more fun than ever because I was becoming more efficient at it.

My mother was very religious. My mother called my drawings–I drew people mostly–”Arnold’s monkeys.” She didn’t hang my pictures up. Because it was a graven image.

How did you handle it when there was no work coming to you?

You get pretty desperate pretty soon, when you’re just a freelancer, as I’m sure you must know.

I feared having a job. This was when I first started out, and I had absolutely nothing. And because I didn’t want to be caught in the villain’s clutch. I see life as being lived that way in some cases. And so having freedom, the looseness of being freelance, where you do the picking and choosing.

Of course, you know, have to make a living. Pay the rent. But I liked that whole feeling. I didn’t mind the chance that you’d get some real tough times. Because it happens. But it was worth it to have the fun of the really good times. But remember the golden age of magazines was still happening.

It was coming to an end. But it was far from the end. There are cartoonists, famous, Beetle Bailey, Mutts. There’s this newspaper company that keeps buying newspapers and they’re not publishing the comic strips anymore. The guy who draws Mutts lost 50 papers when this happened to him. It’s a very tough time. And I don’t know what the real market is. What’s the next big thing?

Do you have a preferred pen point? Do you like the big ones or the small ones?

Both. But not the great big ones. I could manipulate even a very fine point. And I really became very adept at it, I must say, without bragging. But that was necessary.

I have lots of points I’ve collected. I thought the day will come when they won’t make them anymore. Or they’ll be so expensive.

I know Charles Schultz bought out a company when they stopped manufacturing his favorite point. Do you have a favorite ink?

I did for years, and now I can’t think of what it was called. But it was a very good quality. And it had camel urine in it.

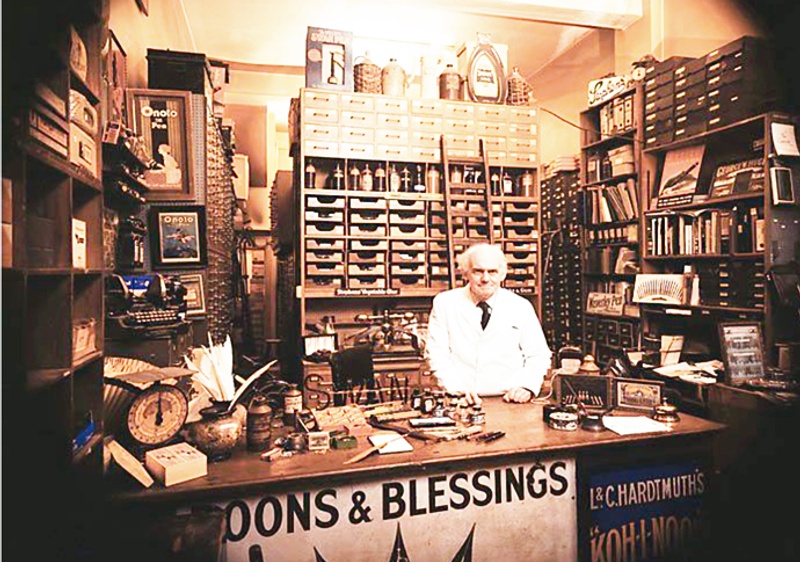

There’s a man in London, England, and he has this very small shop [called His Nibs]. I haven’t been there in a long time, but he always had long lines of people. And all he sold were pen points. And there were people from all over the world in that line. Because they became harder and harder to locate. And eventually, I think he was the only source in or around London. I know just where it was located. I’ll show you on a London map just where he is, as a matter of fact.

And Michael ffolkes. I mean, the English guys, when I first found out about this place, even they didn’t know about it. And boy, they’d be so happy to know that there was a source for pen points still existing.

Let me just say this. I think when people find your drawings, it lights up their minds and it makes them happy. They made me also feel like there’s a certain madness there that is liberating from whatever staid conditions are around you. So I just want to thank you.

We’re all in this together.

Arnold Roth Recommends:

My 5 favorite sax players, who I grew up loving and was influenced by:

Lester Young

Charlie Parker

Stan Getz

Coleman Hawkins

Sonny Rollins

This content originally appeared on The Creative Independent and was authored by Paul Barman.