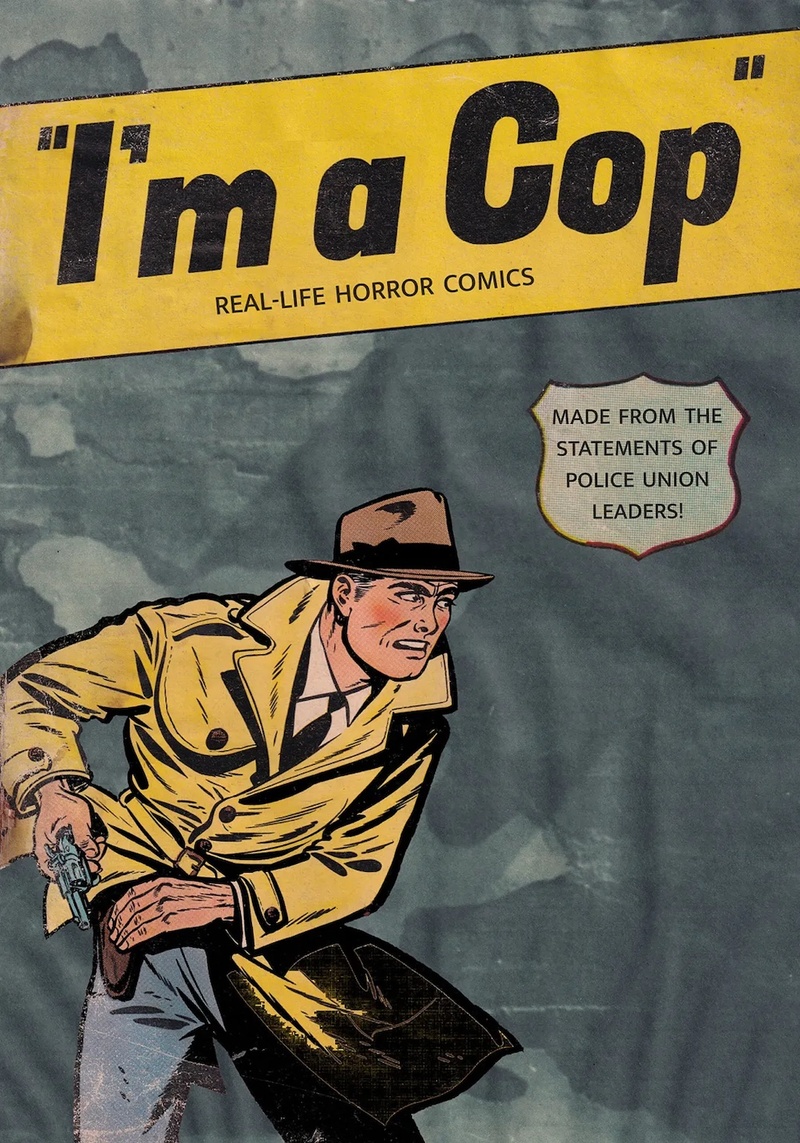

Your latest publication, “I’m a Cop”, combines words taken from actual police union leaders between 2020 and 2022 with images pulled from 1940s and 1950s horror comics. What is the process of connecting these elements to “showcase the ghoulish psychology of policing and challenge readers to see the real-life horror in what the police have been telling us all along”?

I make comics in a very, very strange way. I don’t know anyone else that makes comics like me. I start with a really basic idea. The first part of the process is reading and collecting. I have files and files worth of police union statements, of transcripts of things that police said, dumped in a Word doc. I stayed with it for a little bit, and then I began looking for ways to isolate and highlight certain themes, taking a lot of time to try to find the synchronicity—that’s a really pretentious word—the echoes, I guess, between text and image.

My page layouts all come from this comic called Planet Comics from Fiction House, one of my favorite publishers from the 1940s. They have crazy panel layouts because they’re from the early days; they’re really experimental. I scan the pages, take all the content out, fill in the text boxes digitally the first time, then print those out as empty panels. When I first started doing comics using collage, I was treating it like a puppet show. I would cut out little elements, I would print out backgrounds, and I would stage photos that would be put into panels. I think some of those images are striking because of the way they use depth, but those pages ended up looking too digital for me.

Why is physicality important?

Comics read well digitally. But there’s something about them when you make it into an object. I’m working with really old comics and I think it’s especially interesting how they’ve aged and decayed. I want to capture that in the work, and in some ways exaggerate it. I take an already degraded page—because the comics I’m working with are falling apart—and scan it in with my totally cheap scanner, and then I print it out with my ancient inkjet printer. Each step of the way, it gets further and further degraded. So while aspects of that process are digital, it always comes back down to this emphasis on the physicality of the age of it. “I’m a Cop” feels new, but it is also weirdly tactile—a little uneasy and off-putting.

How does the comic-book medium uniquely work for broaching the topic of police violence?

Crime comics have always been tied into propaganda. Certainly superheroes, which in the U.S. we think of as the dominant mode of what comics are, there’s a lot of fantasy and space to play while being based on a cop mentality. The notion of criminality, the notion of people being inherently evil, and the notion that it’s okay for a more powerful figure to commit violence against the less powerful figures—that’s all part of the baggage of U.S. comics.

Viewers interact with comics a bit differently than how they interact with other mediums. Comics feel easy, but formally, when we read them, we’re doing a lot to make sense of the page. Time doesn’t make sense in comics. It’s not logical. We just smooth that right over. I think that means that comics can be an ideal space to offer challenging material for people in a way that they don’t recognize as challenging.

Who is your audience, who did you create “I’m a Cop” for?

I have no idea who my audience is. I never have any idea who’s going to read my work. All my stuff is nonfiction, and I always work with voices of other people. What I’m interested in is seeing if I can expose people to stuff I hear about that I don’t think they’re paying enough attention to. With cops and the uprising in 2020, I was in the streets. But I’m not going to be like, “Hey, I’m an expert on this.” I’m not going to inject my voice into a conversation unless I know I have something to say.

I realized that what could be added to the particular conversation about policing—about reform, abolition—is listening to the police. The amazing thing about their unions is that they function as sort of a collective voice and they straight-up say who they are, showing that it’s very much on the surface why policing is so rooted in violence and why this repetition of violence isn’t going to go away. And the utter disdain they have for the public. Almost everything I pulled out in my research was from press conferences, so these were public statements people have been exposed to. But I’m like, “Have you been paying enough attention to this?” How do you get people to pay more attention? You put it in a totally different form.

How do you handle spending so much time with hateful material? Or with material centered around defeat and disappointment, as is the case of Failure Biographies, your project on forgotten artists who once had big dreams?

I always have several projects going on at once. So I’m able to pull away from it. The police union project was something that I always worked on alongside other things. I probably checked in every day on police unions as the actual research part of it. One of the reasons that I finished the comic—and why I didn’t even try to contact my publisher and decided I was going to put it out myself—is because I just had to be done with it. I couldn’t spend any more time with this text and this toxic material. Then you take a little break. Then there’s the reception. I’ve been talking to a lot of people who sent me all their own research and journalism into police unions. I think I’m going to do another volume, which I was not planning to do. I feel like stepping back into the mud.

Do you feel a sense of responsibility to produce another volume?

I think there is a responsibility in getting the project right. When you’re dealing with a subject this fraught and this serious, I felt the need to, for instance, take really good notes. I don’t usually put full citations in the back of my works, but I wanted everyone to know exactly when and where these cops said what they did. Readers are going to ask you about the subject you’re making work about. I don’t know if that’s responsibility. I think it’s like an invitation. People continuing to respond invites me to continue the project; if it just disappeared immediately, I might not. So “invitation” might be a slightly more positive way to think about it.

I love that answer because I think a lot of people struggle with political art and its ability to affect change, if that should be the point of it at all.

I feel like that’s what I have to offer in all my work: being like, “Hey, would you consider thinking about this thing that is hard or uncomfortable to think about?” It’s a reason why we see a lot of educational comics, not that they’re very good a lot of the time. There’s something about comics that might be useful for this idea of opening up spaces for conversations. Comics always catch us off-guard.

You’re an educator yourself, a lecturer in the English department at San Jose State University. How do you balance that with making comics, which might seem incongruous on the surface?

Academia has not been super kind to me. I’m a contingent faculty; I’m probably lifetime contingent faculty. And I got a doctorate, you know. But one of the reasons I stick around is I need to use the libraries, I need the access. I really, really value breaks. If there’s any advantage to being a lecturer, it’s that I’m not required to do anything over breaks. If I figure it out right, I get almost four months a year that I don’t have to do anything related to school. I’m fiercely protective of that because that’s when I get so much of my own work done.

In terms of balance, the bad news is that I’m always too busy. But weirdly enough, I’ve sold enough comics right now to be able to teach a little less. That’s an advantage of this life: if your career is heading anywhere, in any way that can give you any money, you can subtract a little from your other responsibilities. It’s not ideal, but I worked in bars and music clubs for a long time, and this is better. I created the whole time I was working in the service industry. But academia, while a lot of it is draining—it’s a totally flawed system—you do sometimes get rewarded for your ideas and intellectual labor. In the classroom at least, we get to talk about ideas that certainly feed the art, feed your interests, feed your research. I teach creative writing. I teach a class in the history of comics, which has been enormously useful for me because I’ve always made my comics from the perspective of old ones.

I imagine it’s nice to feel like your creativity has value to the people around you.

It is, even when people don’t necessarily understand it. My department values what I do but I’m not gonna lie, they’re not always clear on what it is. It probably would’ve been easier for me if my work slotted more easily in specific disciplines. I work between a lot of different disciplines and that’s what is most rewarding to me in the arts, but it’s definitely a challenge on the academic job market.

Is it not a challenge in the art market, too, to pitch such hybrid works?

I’m a minor member of a number of different artistic communities. I hang out a little bit with poets. I hang out with cartoonists. I also hang out a little with academics. I met the guy who wrote the afterword for “I’m a Cop”, Travis Linnemann, because I’d been posting samples online as I was making it. He contacted me one day and it was like, “holy shit,” he has this book about U.S. policing and horror tropes and our two projects really seem to be in relation. In conversations with him and through him, I have been connected with quote-unquote “real” academics who study criminal justice, or cultural criminologists who are messing with data. I’m not a member of those communities but it is a real privilege that the arts would be an entry into them.

What does your ideal workspace look like, when you’re shifting between modes of creation?

I’m never going to have an ideal workspace. I live in Santa Cruz, California, and I teach in the Silicon Valley. It is so expensive here. I can’t imagine ever being in a place where I could justify having a studio space; I can’t even justify having a room. I have a corner in my bedroom with a nice, big desk with all my materials. During the pandemic my daughter was taking school online just feet from where I’m working. I literally have a guy with a leaf blower outside my window right now. It’s not the absolute best space, but it’s been an enormously productive space. To me, it’s like, what’s the bare minimum I need? How can you make any space into your space? If nothing else, I just need a space where I can have stacks and stacks of things sitting out at all times. I need 4 feet by 4 feet where I can cut things up.

Have you always felt the need to create no matter the circumstances?

I got my MFA in fiction and for a long time I thought I was going to write novels. I don’t regret it, but I never was satisfied with the final outcome and I think it’s because I wanted my medium to be distinct, to figure out a way to do things that other people weren’t. The work can be in lineage with other things—because everything is in lineage with other things—but I want the actual product to not resemble anything else. I wrote an unpublished novel that was about making comics and there was actually a comic within the book. I had this idea that half my book would be an attempt to translate comics into text; I would do these weird descriptions of what panels looked like. And it was interesting, I don’t hate it. It’s in a drawer somewhere. But at some point I was like, Oh shit, I just need to be making the comic.

I didn’t go to art school. I’m someone who studied art and art history. I studied comics because I was really obsessed with comics. I came to it feeling like an observer. Sometimes, if you’re really obsessed with something, maybe what you want is to step into the space. At least try it. You might already be in the space. We tend to feel like everything is operating through cliques and scenes and movements, but I believe there’s actually less of that than we think. People aren’t going to give you permission to step in because it doesn’t occur to them that they need to give you permission. I’ve found indie comic artists to be a nurturing and beautiful community, but no one asked me to join them. I had to start making first.

Johnny Damm Recommends:

No More Police: A Case for Abolition (book) – Likely the definitive book on the subject and entirely indispensable.

The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (book) – All about rogue academia and the people hanging on at the bottom of academia figuring out ways to survive and perhaps exploit the resources.

Moor Mother (musician) – Musician/poet/Black Quantum Futurist Camae Ayewa has seemingly released dozens of LPs since 2016, and they’ve pretty much all been amazing.

Endure by Special Interest (album): I’ve basically had this record on repeat since it came out.

Love and Rockets (comic book series): The greatest U.S. comic of all time.

This content originally appeared on The Creative Independent and was authored by Greta Rainbow.

Greta Rainbow | Radio Free (2023-01-18T08:00:00+00:00) Comic artist Johnny Damm on forging your own path. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2023/01/18/comic-artist-johnny-damm-on-forging-your-own-path/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.