What does being of service mean to you and why is it important?

There must be some sort of tangible output, spiritual, emotional, intellectual, artistic output to the community outside the art audience. Being of service just means sort of shape-shifting with what the needs of folks in the neighborhood have right now. It means being present, being available. It means recycling and redistributing resources, both poetic and tangible, informational, intellectual back into the neighborhood that I deeply love. Utilizing this neighborhood love and pride I have for art-making, of course, but also for other conceits, and just seeing it out in the world.

I’ve been trying to do it since 2010 when I entered art school as an undergrad, but 10 years later, now that I have a gallery, and they commercialize my work for me, it helps to build social programs and provide financial support to other organizations also doing the work. I’m able to engage on the street-level in the way that I’ve always wanted to. I’m finally doing it, which is really cool and meaningful. It’s always just been a core part of the desire of even wanting to make art.

Lauren Halsey, Slo But We Sho (Dedicated to the Black Owned Beauty Supply Association) II, 2020, synthetic hair on wood, 72 x 101 1/2 x 8 inches, Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

Is this model of balancing a high level art practice and high level social practice something you hope to pass on to young people and others around you?

I’m not trying to convince anybody of anything, I’m just doing what I’m called to do. For example, my father was an accountant for private firms, for the city of Santa Monica, and at one time the guitarist, I think, it was Slash from Guns N’ Roses. He did his professional job well on the West Side and always brought resources back to South Central as part of his personal ethos. I can think of 90 million people in my life who have had different paths, different relationships to me, but were also part of that pantheon of folks that I knew I wanted to be like—always of service, always organizing.

I move the way I move and if it’s inspiring, that’s amazing. But people are going to live the way that they need to live, and that can mean anything and that’s totally appropriate. I don’t hold anybody towards an expectation. If anything, I’m only heavy-handed with my little cousins and I’m very hands-on and insistent about including them in a lot of the programs that the [Summaeverythang] Community Center does because it’s good to build that into their identities very early on. They’re my cousins so it’s different but as far as people I don’t know, I put it out and take what you want to take from it.

Can you talk a bit about geography and space and the kind of stimulating energy that you find in your community?

Like I said, it’s very biased. My biography and everything that I’ve inherited energetically—some stuff kinetically and then the literal stuff: the language, the archive, the histories, the South Central artifacts, the stories, the pictures… loving all of those things and wanting to be a custodian of all those things in the most intentional way. Then also growing up with friends who also have that same sort of relationship to the neighborhood who are now in my studio. We’re coming up as adults, feeling this sense of love and honor and pride about being where we’re from. A lot of that is coming from our parents, cousins, and our grandmothers, but also just the really cool things that we’re into, like the aesthetic moments that are very, very specific to this street or this corridor. I feel we’re constantly discovering, which is great. I love it. It has its problems, it’s not Disneyland. This place is fucked up too, but I’m from here.

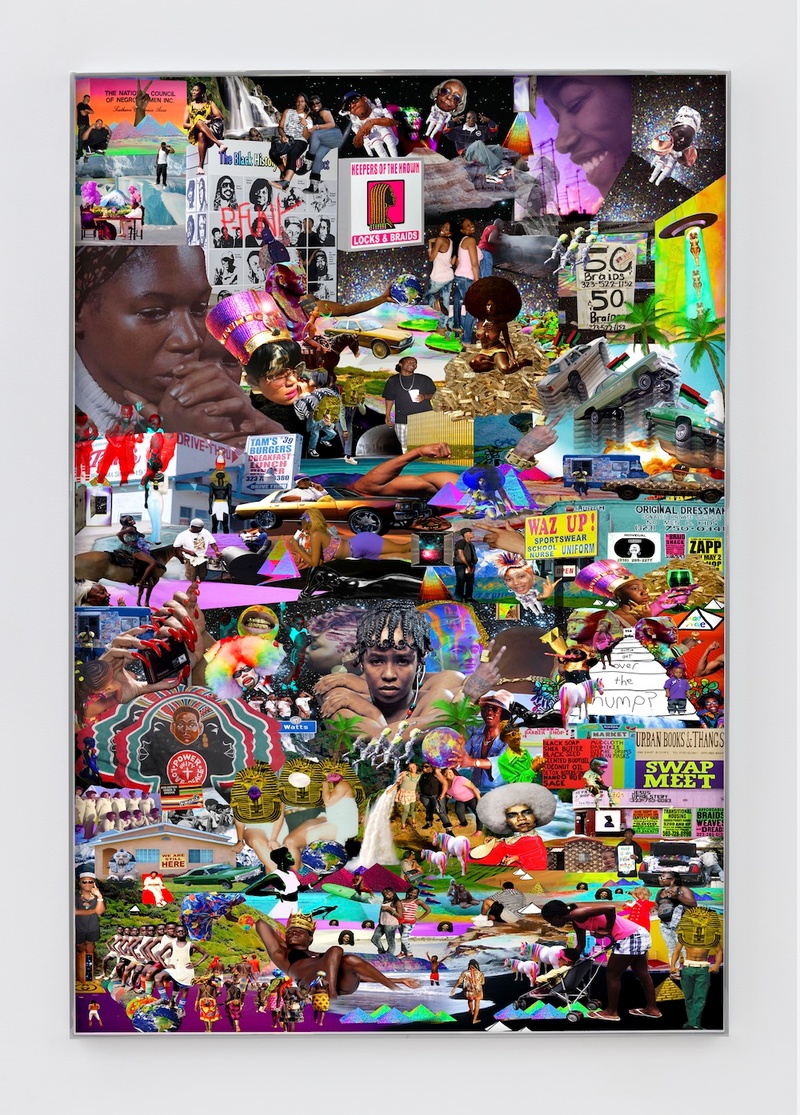

Lauren Halsey, Loda Land, 2020, inkjet print on paper, 67 x 45 1/2 inches, Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

Can you talk about the importance of fortifying against the danger of development and outside ownership in a community that has such deep roots and a multi-generational creative continuum?

When you own something you control it, to an extent. Generationally, you can think about how this space might operate in a larger community context or in your family. You get to function in a space without the mess of bureaucracy. We can, to an extent, determine our needs, palate, tastes, etc. We can protect it. We can care for our archives. You don’t have to depend on institutions to collect them. We can build our own. We can create our own spaces for gardening, for our own harvest. We can distribute that into a community.. There’s all these moments for choice. I’m interested in one day engaging the community land trust model for these reasons.

There’s tangible reality, like the physicality of a neighborhood, but I’m also curious about the power of myth-making. How can fantasy have a tangible influence in the real world?

I’m not sure as far as how they land on folks and how they sit in people’s hearts and minds, but for me, I make large-scale sculptures or installations that have this architectural vision through a very fantastical frame and lens because I want to compel folks and myself. I make them for myself and share them with other people, but I want to compel dreaming, new aspirations, proposals for the future and actually do it. But then also, growing up in a neighborhood where architecture and the visceral feeling, body feeling, of architecture here and its materials—it’s cladding and can be very disempowering. I don’t mean the homes. I mean a certain county building or a certain high school. Not all of them, but there are these moments or these markers where it’s just like, someone made these decisions in response to a very racist, and most likely classist lens about South Central.

I’m interested in, one, making gorgeous black space for Black people, but also spaces that just aren’t about beautiful form, but embody what I hope to be future spaces that are actually functional in a neighborhood as habitats. Not just representations of architectures as maquettes in an art gallery or museum but the everyday experience of living with it and in it. Right now I still think I’m in model-making form, even though it’s human space, but eventually I think the spaces should exist on the block. I’m not saying it will ever be this, but just an extreme example, if it was a liquor store or mini market without all of the baggage of cladding and signage, “No loitering, no gang-banging, no guns, no washing your car on the premises.” I’m like, “Fuck, I’m just trying to buy a bag of chips.” You go in and there’s all of this surveillance and all of this armor to protect the person behind the register. So, to make these like fantastical, smart, light, poetic spaces where we can actually function. I think that would sit well on the hearts and minds of folks in a way that we’re not able to function in regular spaces now, because the stuff is so harsh.

Lauren Halsey, land of the sunshine wherever we go, 2020, mixed media on foil-insulated foam and wood, 97 x 52 x 49 inches, Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

Yeah, people bloom and blossom when they don’t have that psychic barrage. You’re very sensitive to the ability to create ideal worlds through your art and visions. How does it feel being in a space that you’ve created?

I’m trying to chase the high I’d get in grad school, building a space in solitude over time in the studio. There wasn’t a Fire Marshall, there wasn’t the press, I was able to accumulate over a nice chunk of time. I mean, of course there were deadlines, but they were sort of abstract. Building something was still very much in my control. I was able to go into tangents. I was able to literally live in the sculptural installations I was building at the time. Whereas now, I enjoy it, I wouldn’t do anything else, but there’s a lot of pressure that shows up when you professionalize passion for a commercial context. There’s a lot of labor, a lot of staggering deadlines, money, time, effort, and just all this thick stuff that goes into building and making something. When I see it, I probably have 10 seconds of deep joy and then my mind then starts thinking, “Well, what’s the next one?” I think I’ll continue to sort of operate in that thought process until I get to the real scale of architecture which I’ve been trying to reach since 2006.

With success comes responsibility, more of the administrative hustle to enable the mechanism to function and less of the dreaming which is the reason you got into it. What would you ideally like to see for yourself down the line?

I care very, very much about the people that work with me and I care very much about their comfort. That’s just a huge thing for me. I want my studio to feel like a family. I think it does. I want to pivot in the future to having my own space within a studio, not sharing an open floor with everyone, which is what it is now. I want to be able to have my private moment to feel free and be at play with the work. Right now, it’s very hard to go to that space—a head space, heart space, creative space, where I can make a mess, fail, land, and still experiment while other folks are in the room, 20 feet away mostly because my studio has run out of space. I want to be able to just build a deeply personal installation in the studio as a habitat I live in, not to be exhibited. Something like that might take three years, but I just need to do it.

That kind of re-imagination of space through your lens seems very powerful. I think about Noah Purifoy and the kind of reclamation of discarded materials that in his case, had a lot of heavy weight. The materials you use are infused with a vibe, almost a coded language, like a portal into your community neighborhood. For you, the reclamation of discarded materials, what’s the power in that?

I wish I used discarded materials more. I would save a lot of money. I’m obsessed with what people make with their hands so I’m constantly buying from makers in the neighborhood at all levels of production—incense, oils, mix CDs, movies, painting, textiles. I intentionally collect and archive all of these things and I use them in my work when it makes sense but primarily for our community archives. But the ultimate goal of the exercise for me is that one day I will have a space that’s able to hold our archives, literally. And the archive is made on the street level first, archives that might not make it into the institutional space and if they did, I don’t know that I would want that. I want folks from this place and others like it, to be able to go into the incense collection and understand new references and deep histories behind a title or scent, for example. I’m also collecting the process and production of the things, how they’re made, how they make decisions, not just the result or the object. And folks get to download all of that too, so that in the future, when people think of incense and, “Oh, I mean, you burn it. You change the energy in the room,” or these very esoteric ways that we think about it now. I can say, “Yeah, and there’s this dude Leon, who’s a hardcore poet and he writes poems with the goal of then producing a scent for it. Then he tries to summon some sort of title for it, from the scents that he creates and that’s how he gets the title. It’s not just the stick.” And then I have the interview with him, talking about it. I collect all types of stuff. Some of it shows up in my work, but like 99% of it doesn’t. I do that with the goal of one day having South Central research archives for the world to see. So I think in 10 years that will exist, maybe even sooner. It’ll just be how people access it, I have to figure that out.

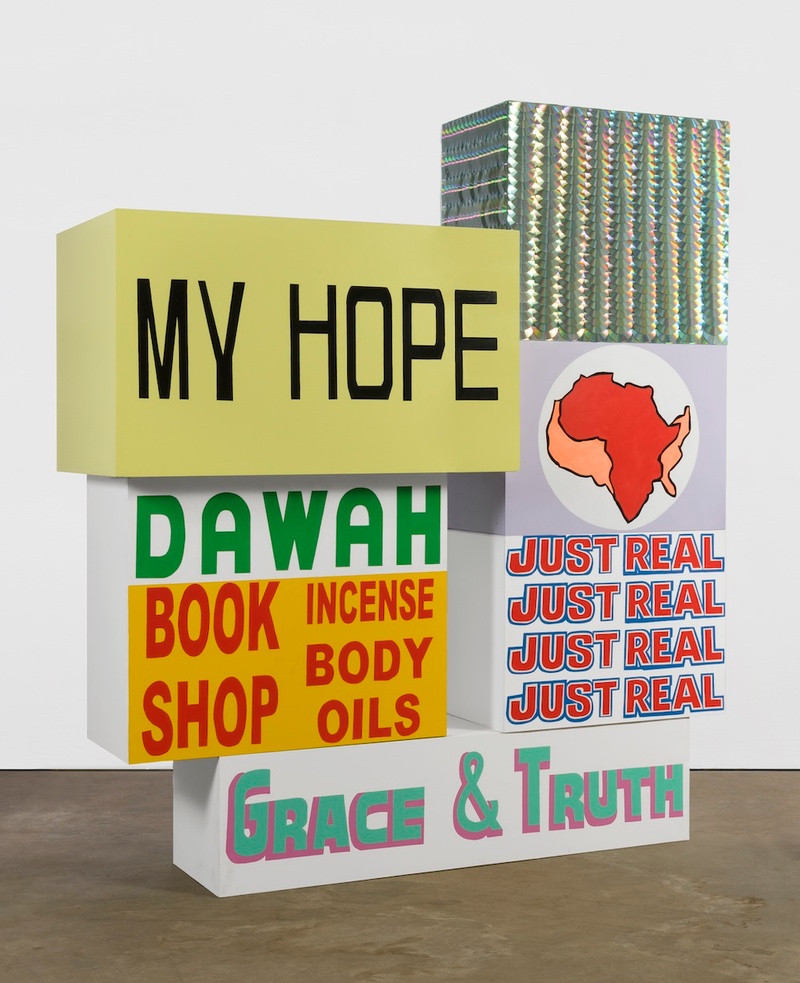

Lauren Halsey, My Hope, 2020, acrylic, enamel, and CDs on foam and wood, 116 x 101 x 36 inches, Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

Amazing, I love this idea of the archive. Within your social practice and your arts practice, do you think about nourishment and what the nourishing effect will be for the person who engages with it?

Not so much, that’s too much work. It’s already hard enough to build it. But, when I decided I would have a Community Center that was part of the thesis. But I pretty much wear all of the hats and I get caught up in logistics and a lot of that stuff gets put on the back burner, and a lot of my thinking and brain space around it is just like, “How do I make the produce land here?” But I think after Corona, I think I will be able to have a sort of intimacy with the community and the project and it’s trajectory beyond just, “Here’s a box, and I might not ever see you again.” I can actually really embrace the word nourishment and I can embrace those relationships on another scale. And actually being of service in a very long-term sense because we don’t have to be physically distant. Right now I can’t even go there because I’m just trying to keep everybody safe and we’re just trying to get the boxes out. But in my dream world, when we pass this moment, there will be a totally different engagement. Not just giving out the boxes, but following through with, at the minimum, recipes and cooking classes, and trips to the farm, and holding the grocery stores accountable for the horrible produce supply chain that we get in South Central, Compton, and Watts. There will be multiple actions, not just one. I think only time will tell because I’m also just figuring it out as I go.

600 bountiful boxes of produce per week, from farm to Watts. Nourishment ups the quality of life. How would you articulate the thesis of the Summaeverythang Community Center?

I don’t know yet but I call it Summaeverythang because it can be in and of everything, and can exist across multiple or plural contexts, no matter what it is. It can be a space for job creation or it can be a music studio. It can be a class for Capoeira. Whatever is for the advancement and transcendence of folks in the neighborhood in that moment is what it should be. It could literally be anything that feeds and nourishes an intellectual space, a heart space, emotional space, psychic space. It could be anything. It could be sign painting classes.

At the highest level.

At the very highest level. It was important that we didn’t do a food program that was about replicating what’s already in the grocery stores, which I have a huge problem with. It’s about not being afraid of the cost and not giving folks the crumbs. So doing what I have to do as an artist in my studio as far as production, to fund it, and then doing all the things that I had to do to become a nonprofit, very rapidly. Then doing all the things to now activate that to its fullest potential by hiring a grant writer, staying in conversation with them, constantly applying to things, and now trying to do my due-diligence to figure out alternative streams of revenue because grants aren’t enough if I want it to operate at a very high level. So it’s all about taking a step at a time, and just trying to get there. But one day, when it opens to the public, it’ll be all of these actions happening simultaneously, whatever they are. In my dream world I’ll be able to hire Debbie Allen’s Dance Academy and do three months of free classes, four times a week for dancers in the neighborhood. She’s the highest level that it gets. So that’s what I mean.

Summaeverythang Community Center, Los Angeles, June 2020, Courtesy of SLH-Studio, Los Angeles, and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles

The highest actions can co-exist with humility. You put a note out there at the beginning of the food program, “My lane isn’t food advocacy, so if mission-aligned folk out there want to collaborate or lend some advice, hit me up.” I think the ability to come at it with professionalism but also humility, to make it a collaborative effort, is really important.

Yeah, for sure. Which is why I work with who I work with, why I work where I work, why I hang out where I hang out. Because as the practice becomes more successful, the artwork, studio, my relationship with the gallery grows, I’m not interested in separating the success from the neighborhood or the subject or the story that I drew, or the incense designer that I buy from. You know what I mean? As long as there’s Black and Brown South Central, I’ll always be here. I’m not saying that people that leave and don’t come back are problematic, but I’ve never had that interest.

Your work speaks very powerfully. I think about the hand painted signs that you often use in your art. If you were to make a sign to amplify your message and vision as a human what would it be?

It would be simple, “Lauren ‘n’ thangs.” It’s part of a vernacular, whether I’m in South Central or I’m in Atlanta and I say, “’N’ thangs” people know exactly what I mean and what that portal could mean and not mean. It also just suggests, you don’t know what you’re going to get. I would say that.

Lauren Halsey Recommends:

CocoEgypt (Incense)

Ramsess (Artist)

Sevshaw (Album by Six Sev)

“The World Is A Hustle” (Song by Ms. Lauryn Hill)

Planet Splurge (Place)

This content originally appeared on The Creative Independent and was authored by Mark “Frosty” McNeill.

Mark “Frosty” McNeill | Radio Free (2023-02-10T08:00:00+00:00) Artist and fantasy architect and builder Lauren Halsey on being of service in your creative work. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2023/02/10/artist-and-fantasy-architect-and-builder-lauren-halsey-on-being-of-service-in-your-creative-work-2/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.