Robin Waples: University of Washington (NOAA Fisheries, retired)

Topic: On the shoulders of giants: Under-appreciated studies in salmon biology with lasting influence.

In 1675 Isaac Newton wrote, “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.”

This idea epitomizes the way that science progresses by incremental steps, punctuated occasionally by major breakthroughs. But often it is the case that neither these ‘giants’ nor their research are well-known or even routinely recognized.

I discuss four such studies conducted in Oregon that have had a profound influence on scientific developments in salmon biology in subsequent decades:

1) a 1960s study of southern Oregon Chinook salmon that was the first documentation of what has come to be known as the Portfolio Effect;

2) a 1970s study of Deschutes River steelhead that was the first attempt to empirically evaluate genetic differences between hatchery and wild fish;

3) a 1980s study of family size variation in Oregon coho salmon that helped pave the way for entirely new lines of research; and

4) a 1980s report on age structure and relative fecundity for Oregon Coast Chinook salmon that provided crucial empirical data to help parameterize models of the rates of genetic drift and loss of genetic variability in Pacific salmon.

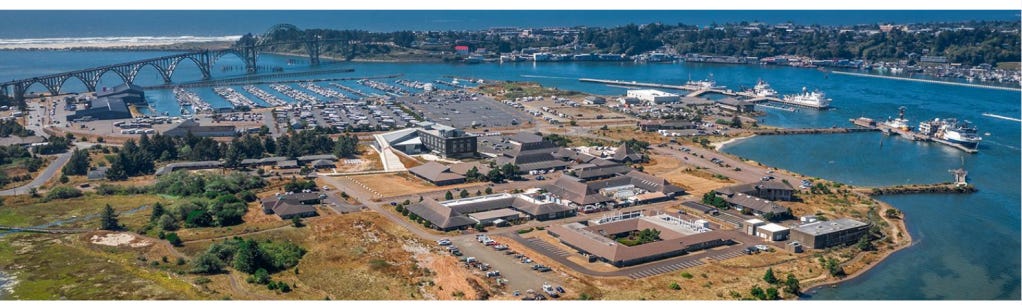

I attended the talk just to be in situ at this Hatfield Marine Sciences Center and see what this 76-year-old fellow had to say = Robert Snowden Waples, Jr., born in Berkeley, California. He attended Palo Alto High School, where he excelled in swimming; he went on to Yale to major in American Studies and to swim, competing with the likes of future Olympians Don Schollander, John Nelson, and Mark Spitz.

He has been at the forefront of wild salmon (and now hatchery salmon) research. He has been cited more than 25,000 times, has a plethora of articles, and he is credited with helping put some teeth in the endangered species act for salmon wild species. That is, he and others worked on the various genetic lines within species so they might get special categorization.

The ESA was set forth to bring a species to a status where it doesn’t need that endangered status. There are more than 50 percent of salmon species listed under the ESA.

The Bristol Bay sockeye salmon fisheries has been and up and down situation. There are 20 to 30 different stocks of Coho salmon, and with sockeye, resiliency, representation, and redundancy are key to keeping this ecological area sustainable, Robin states.

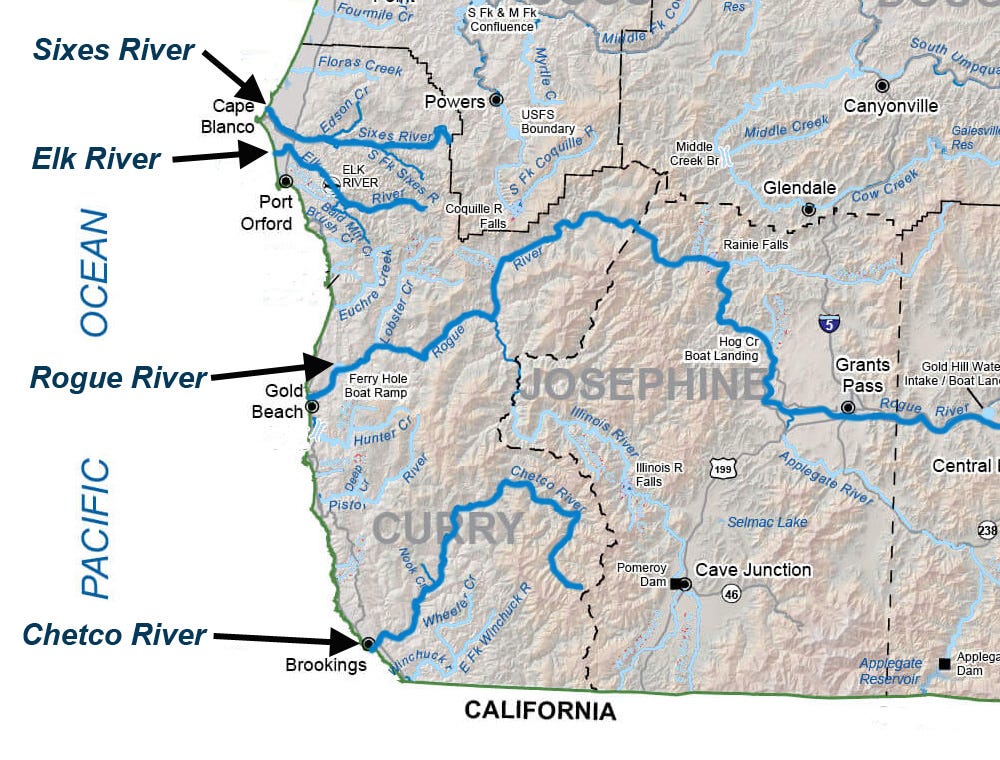

While the talk was dry, and there were no photos or videos, graphics from Madison Avenue, he did his talk hoping the audience there was keyed into learning about the top four articles influencing him and the science of salmon research. The first article he cited was “Biocomplexity and Fisheries Sustainability” concerning fall Chinook salmon on the Sixes River, OR.

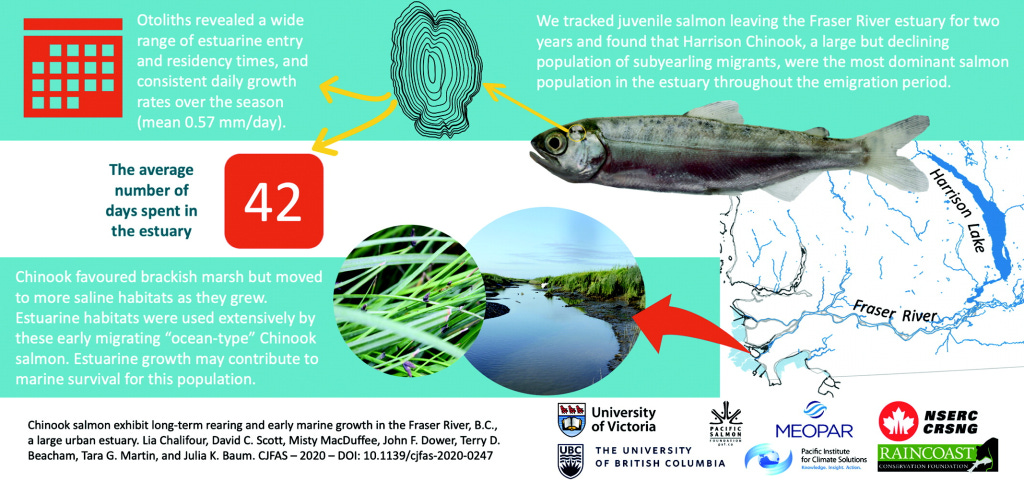

Crazy science, including the slow work looking at adult returns using interesting criteria — fast to the ocean once hatched in home stream; a little time in the estuary after hatching; a lot of time in the estuary; a lot of time in home tributaries; yearlings staying in fresh water for a year.

What helps with survivability. While the 2, 3 , 4 and 5 year returns included mostly those in the third group = a lot of time in the estuary before maturing and heading to sea. This was done in 1965, without Google, the internet and so many other tools.

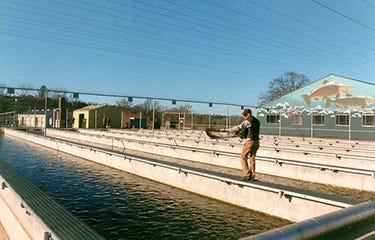

The next article on Robin’s top four list includes looking Deschutes summer steelhead and the genetic differences in growth and survival of Juvenile Hatchery and Wild Steehead Trout, Salmo gairdneri.

The question posed in the 1970s research includes: What if there were no hatchery fish? That is, what would that effect be on wild fish? They call that hatchery supplementation since so many wild stocks (more than 50 percent) are endangered, in peril.

The research Robin goes over gets even more deep in terms of genetics and determining the status of coho salmon from WA, OR, and CA. That one was published in 1995.

Lots of work on wild populations and reproductive isolation and life history traits — they can be adapted to local areas.

He cited Valley Creek, near the Sawtooth mountains, where the salmon move from the ocean 900 miles away up to around 6,500 feet in elevation.

Of course, the questions from the audience include: what about the effects of climate change on the salmon community. Robin says there are tons of studies on how salmon sustainability will be changed by warming land and ocean areas. The southern range will have a more difficult time. The northern area will see salmon expansion as the ice recedes and the water gets warmer.

The big questions are around what sort of evolutionary changes can help them keep up. These are called evolutionary rescues, but he says warming seas might be too quick for that rescuing to occur.

Reduction in forests and such stream imperilment really affects salmon. Non-point source pollution is huge. More people are changing the land, through urbanization and agriculture. Rainfall and impervious surfaces add pollution loads. Robin states that there is great support for salmon, and most recent polls show 70 to 80 percent of people want to work with salmon mitigation and are willing to pay more for salmon survival and be taxed, as opposed to the spotted owl, with only gets 10 percent backing for massive tax increases to save them.

While Robin is not a fan of techno fixes, he is for more streamside tree planting for shading the homes of salmon to lower water temperatures. And making sure water from rainfall gets back into the system clean.

He notes that trout have been put everywhere around the world (trout being a cousin of salmon), and he notes that steelhead and chinook have been put into Patagonia rivers starting a hundred years ago. New Zealand has also introduced Pacific salmon there.

Here’s the talk,

I got to talk with Robin for a few minutes. We talked about his American Studies degree, and how he taught English at the University of Hawaii. And what got him into the sciences. We also mulled over why there is such a disconnect from his and his fellow scientists’ research and the average person including the fisher people who live here in our rural community fishing for rock fish, shrimp, crab, halibut, and other species.

Also discussed was the issue tied to K-12 students NEVER being at these events. And, alas, the problem of higher education pushing MBA programs and programs around coding and software application creation.

I introduced him to some of my work, with David James Duncan, with David Suzuki, and Tim Flannery and dozens of other groups, including Save Our Wild Salmon. And there is my “Interview with David James Duncan.”

See also “Flat-Earther Bush’s Style for Wild Salmon (Part III of III)

Saving Salmon, Saving Grace — Busting Dams,” August 31, 2005. And Part I & Part II.

Finally:

A Tribe Once Called “Power from the Brain”

How’d you end up in the Inbred Northwest… What act of fate dragged your Texas butt up here… You exchanged West Texas, Cormac McCarthy, real Tex-Mex food and sun for this? Or some variation on that theme greeted me when I first bivouacked in Spokane after heading to El Norte from “I fought the law but the law won” Bobby Fuller El Paso, Texas.

It was a hell of a Salmonidae journey, hitching my adult body and soul to the Pacific Northwest in the form of the Inland Empire, Spokane — “largest city between Seattle and Minneapolis,” they kept telling me. My olfactory memory burst with narrative skills by traveling the region as reporter, educator and environmental activist. Man, the work I did on writing about removing those four lower Snake River dams. Pieces on sustainable agriculture in Washington. Stories on the power of storytelling in this region of Earth.

This place is full of river-teeth; the place of Ice Age Floods’ erratic boulders dropped 12,000 years ago from ice rafts in the middle of the Willamette Valley; the ramming tectonics and ring of fire. Luckily for me, writers like Rick Bass, Lizzie Grossman, David James Duncan and so many others kept me busy as a desert salmon looking for some home stream back to the Pacific.

I left Sonora and then Chihuahua for Inland Salish land, where 24 distinct languages once ruled.

NpoqÃniscn, or Spokane. For thousands of years the Inland Salish people here built permanent villages along these powerful rivers in order to connect to their lifeblood and make benedictions to brother-sister salmon. Over three million acres made up their distinct territory, and later other Indians introduced them to horses and plank houses.

It’s a place that encompasses a kind of hope trapped in the way the sun hits water through a stand of cedars and towering Douglas firs. “Sun People” Spokane is translated as, though I’ve talked to a few Spokane scholars who say it’s more closely, “the color of the sun reflecting through the water on a salmon’s back.”

That story dredging is what makes a place, place. The legend about my new home is even more poetic: “There was once a hollow tree. When an Indian beat upon it, a serpent living inside made a noise which sounded like spukcane, a phonetic sound without meaning in the tribe’s language. So, one day, as the tribe’s chief thought about those sounds, these vibrations reverberated from his head. Spukcane then blossomed to mean, ‘Power from the brain.’”

Even a thousand years ago marketing rued the day — Spukanee is what they ended up calling themselves. Children of the Sun.

One of my trips deeper into the spiritual and intellectual fabric of this place (new to me starting May, 2001) was with a contemporary Caucasian writer — David James Duncan. We were talking about dam breeching, slack water rivers, President Bush, war, salmon recovery, and writing. That was April 2008:

I’ve been surprised from time to time by the American people’s eagerness to vote for ways to increase their own suffering and their children’s destitution and Mother Earth’s degradation. But I refuse to despair. Salmon are my totem creature and salmon don’t despair. They keep trying to return home to their mountain birth houses and create a beautiful new generation no matter what kind of hellhole industrial man has made of their rivers. Mother Teresa spoke with the heart of a wild salmon when she said, ‘God doesn’t ask us to win. He only asks us to try.’ I’m in the business of trying. I leave the scorecard to the Scorekeeper.

That journey for me, those tallies by the proverbial Scorekeeper as Duncan frames it, is tied to salmon, as the corpuscles of that species have been in my bloodline for centuries. The blood of Celts and of Scots. Why not? The word “salmon” is from Old French: salmonem, salmo, maybe even from salire.

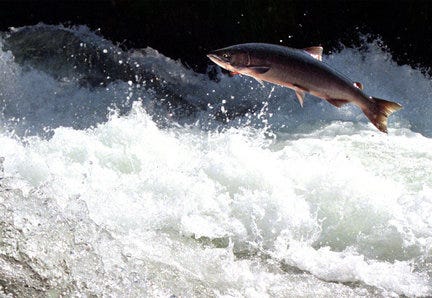

Salire — to leap.

My mother was born and raised in British Columbia, Powell River. The stench of the largest pulp mill in the world at that time was rotting the alveoli of her lungs and hundreds of others’ respiratory tracks, eventually resulting in emphysema, or what is referred to as COPD.

I remember from one stay there how I noticed a line of cars at the town’s free car washes when the day shift switched to night shift. Acid releases, ash snows, rotten egg winds, and automobile paint flaking.

Both her parents were from Ireland and Scotland ending up on the Sunshine Coast. Some call it Sechelt (shishalh) First Nation land, again, Salish (coastal).

I remember pulling in Coho and King salmon, huge ones in the 1960s. In fact, one that I hooked was close to my eight-year-old’s size, at seventy-five pounds. My Uncle Ted (not by blood, but my grandparents’ friend and boarder) had to take over for me, pulling on the rod with his tobacco-stained hands. His own tired lungs wheezed and rattled while he wrestled the magnificent muscular Chinook close to the gunnels while directing me to gaff it.

Here I was, on this boat along this dark-dark forested coast, with Uncle Ted, friend of my Irish-Scottish grandparents. Son of a chief, from the Sliammon Reserve, 20 miles north of Powell River.

That deep red heart and liver were still connected after Ted gutted it quickly — after some word in his native language he exhorted while proceeding to smash the salmon’s head. He put the heart and liver into an old bucket, the one we used to piss in. As I watched the rhythm of that seven-year-old fish’s power train still pulsating with life in salt water, after being eviscerated, dog fish sharks surfaced near us and gulls dive-bombed our foredeck. Just along the beach a mother and her two cubs paraded around that brown bear way, scenting our kill.

That was almost five decades ago.

Strawberries, spuds and these Douglas firs that stayed with me as shapes long after any J. R.R. Tolkien dreams.

Olfactory memory. I recall those smells on a dive boat off Honduras. I remember the taste of Sockeye blood when I was snorkeling off the Baja peninsula into the thrashing sailfish that was in the grips of a 12-foot hammerhead’s jaw.

Once in Vietnam, along the Laos border, in a bat cave with British and Vietnamese scientists, I tasted that Sechelt cedar fire when Uncle Ted took me and my sister to the “reservation” for a potlatch. Dried smoked salmon was on my deja vu mind in 2006 when I was with Nez Perce friends digging camas in a field near Lolo Pass, Idaho.

It’s cliche but apropos to think some of us are shaped by anadromous destinies, like the salmon, biologically programmed millions of years ago by small but mostly large geologic transformations, and the ice barriers, leaking rivers and creeks caused by melting ice. What got salmon going was the changing nature of the oceans cooling some 30 million years ago.

Theories abound, but the prevailing science says they started out as freshwater fish. Moved to the cold Pacific where nutrient rich waters attracted their ancestors.

That destiny to move, to follow some ancient walkabout song or subsonic calling, it’s been an arousing part of my life. I was born on the ocean — San Pedro, California — and then moved as an infant to the Sunshine Coast in British Columbia.

We moved like migrating salmon, hitching our lives to the tether of my old man’s military profession. I ended up teething on the island of Terceira, part of the Azores, Portugal, about 1,600 km west from Lisbon and 3,680 km east from New York City.

Fish, bread, saints and milagros. Miracles. And stories of fishermen hitting the open waters with poveiro boats launched from the Port of Póvoa de Varzim. Thirty oarsmen making it all the way to Newfoundland. Cod, sardine, ray, mackerel, whiskered sole, snook, whiting, alfonsino and salmon.

Also, tuna, migratory and strong. They’ve been recorded by modern biology traveling some 5,000 miles in 50 days. Albacora these fishermen call them.

Piano wires, hooks and barracuda brought up from the depths. I ate their flesh around beach fires, using colorful upturned boats as barriers from the whipping winds. These fishers talked of sperm whale hunts and monsters from the depths west in the Puerto Rico trench.

A uma profundidade de cinco milha, oito quilometros. More than 26,400 feet down.

Later in college, while working as a dive master in the Sea of Cortez, I was boning up for the History of Hispania course I was taking at the University of Arizona. I read about a 1755 earthquake in an undersea “fracture zone-subduction zone” off Portugal — near the Azores. It generated a giant tsunami that went both directions, as far as Caribbean islands. It killed more than 100,000 people and destroyed the city of Lisbon. It sapped Portugal as a going concern — European power — impacting in grand scale not only the religious thinking of the time but philosophical constructs.

Salmyo, Portuguese for salmon. Some of those old salty dogs talked about fishing a river along the Spanish border — Rio Mino — for salmon.

Atlantic salmon.

For me, Pacific salmon, a calling in Salish. Words whispered by the prince and his salmon people, lured me away from that walkabout. We ended up as a family moving to Paris, France, and then Munich and Edinburgh. We harbored in Arizona, where I became, of all things, a dive master. Then, Mexico, Central America, Belize. West Texas, New Mexico.

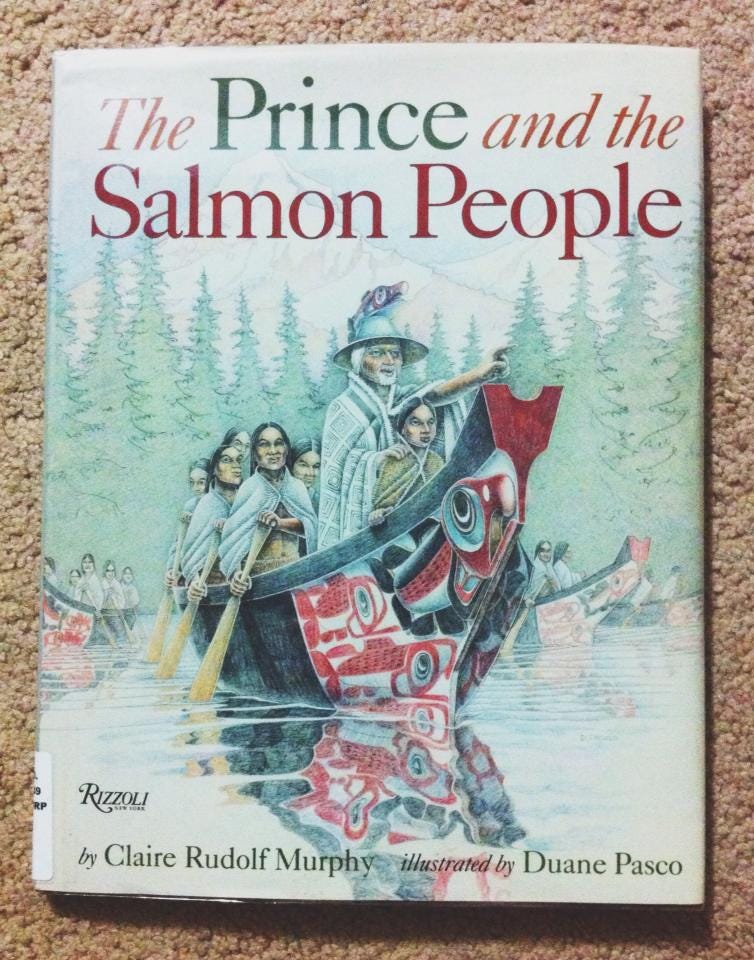

That home stream, that electromagnetic pull, got me to Spokane. I ended up working on a study guide for six through eight graders for Claire Rudolph Murphy’s Tsimshian tale, The Prince and the Salmon People.

I am here, in Vancouver, having traveled from Seattle via Spokane. I just finished work on two magazine pieces around the 70th Anniversary of Hanford, the Manhattan Project, also couched as the A-bomb. That was 2013. My pieces were on downwinders — those people throughout Washington, Idaho, Montana, California and Oregon hit with bursts or radioactive iodine 131. Secret government experiments during the cold war. Millions of gallons of radioactive waste in tanks buried along the Columbia.

The iodine 131 came with the winds and settled into feed, hay. The milk runs to Spokane from Pasco carried the radionuclide with them.

Stories of three-eyed salmon. Sheep born with two heads. My Nez Perce and Yakima Indian friends speak about young girls with cancers. Diseased thyroids for people in their twenties. Aches, pains, stomach ailments, early deaths. Stories of the Pacific Northwest, really, as those waters around Hanford leech into the mighty Columbia as it makes it way to the Pacific.

Salmon made me a storyteller. I have a sockeye tattooed on my right calf muscle. I listen to those sidebar stories. I listen to writers born in the Pacific Northwest. Born to tell the story of their own returned journey.

It’s a story etched in fossils a hundred million years old. Over and over, the stories, yet what is literacy unless we embrace the knowledge that rivers and streams have to be clean, unimpeded, free-flowing, and cold in order to harbor life, to make the salmon. To make warm-blooded storytellers.

David James Duncan:

To learn to live with the earth on the earth’s own terms is more important to me than literacy. I lived on the Oregon Coast at a time when the most ancient Sitka spruce groves in the world were being converted daily into the LA Sunday Times. There was, in my view, nothing in the Times’ stories of that era that compared in beauty or import to the trees that were slaughtered to create the newspapers. The news those trees were emitting was something invisible, called oxygen. The news those trees published constantly was keeping the planet alive. We killed them in the name of literacy.

The end

The Prince and the Salmon People Study Guide, Developed by Paul Haeder and Claire Rudolf Murphy

This content originally appeared on Dissident Voice and was authored by Paul Haeder.

Paul Haeder | Radio Free (2023-03-24T01:34:02+00:00) How Far Do We Go to Save a Species?. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2023/03/24/how-far-do-we-go-to-save-a-species-2/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.