This story is part of a Grist series on Indigenous rights and conservation. It is supported by the Bay & Paul Foundations and co-published with High Country News. Lee esta historia en español. Lisez cette histoire en français.

Transcript

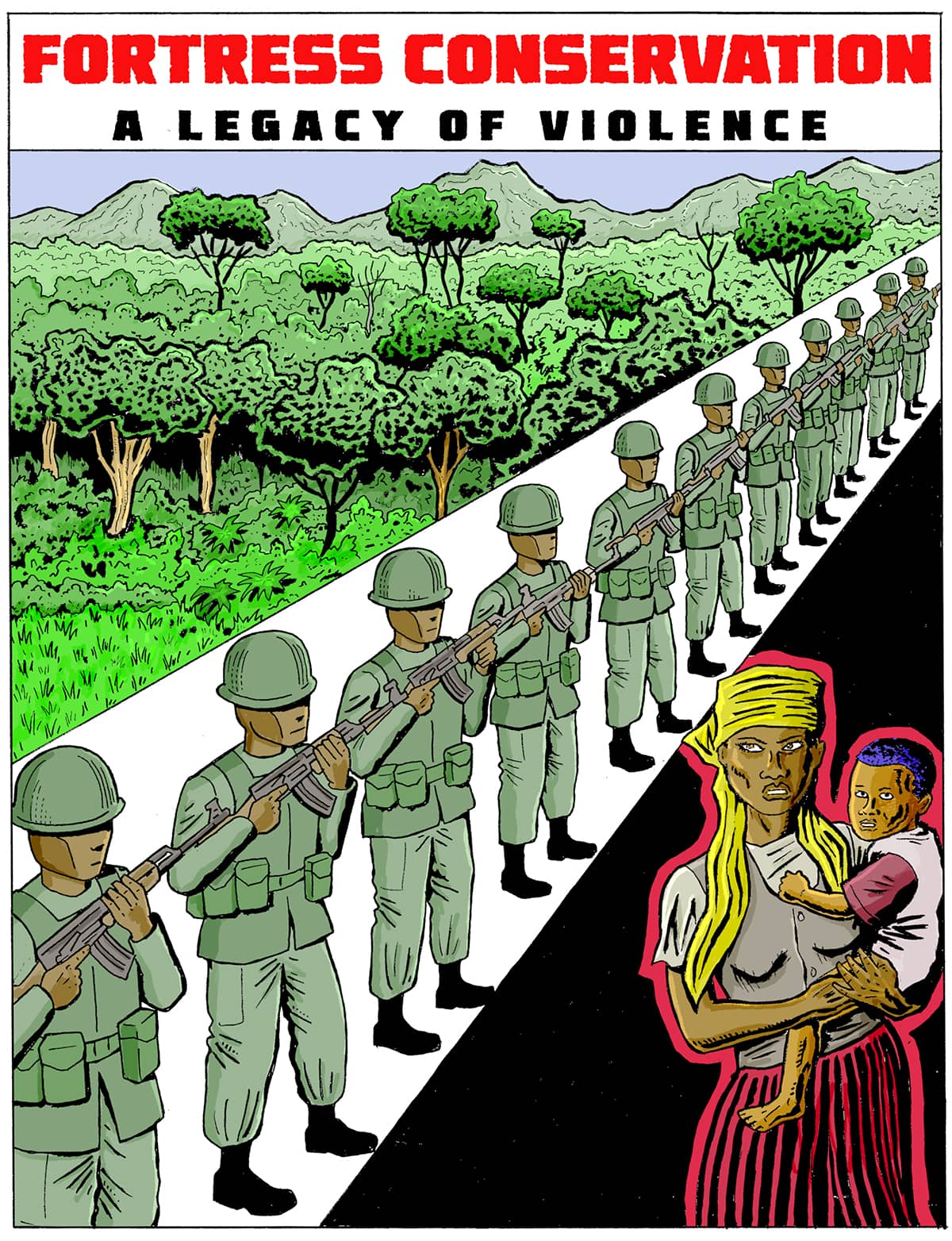

Fortress Conservation: A Legacy of Violence

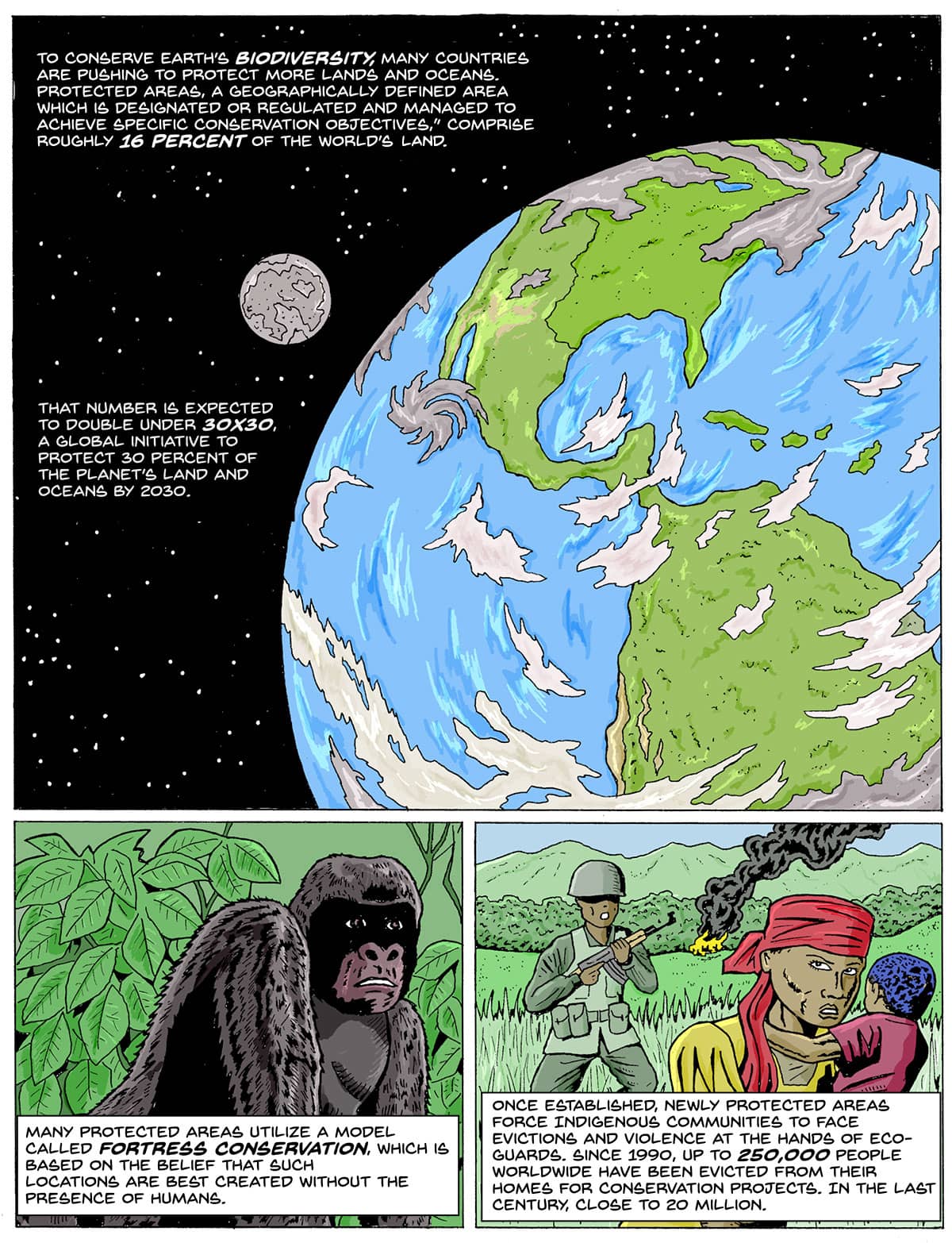

To conserve Earth’s biodiversity, many countries are pushing to protect more lands and oceans. Protected areas, a “geographically defined area which is designated or regulated and managed to achieve specific conservation objectives,” comprise roughly 16 percent of the world’s land.

That number is expected to double under 30X30, a global initiative to protect 30 percent of the planet’s land and oceans by 2030.

Many protected areas utilize a model called fortress conservation, which is based on the belief that such locations are best created without the presence of humans. Once established, newly protected areas force Indigenous communities to face evictions and violence at the hands of eco-guards. Since 1990, up to 250,000 people worldwide have been evicted from their homes for conservation projects. In the last century, close to 20 million.

Yosemite National Park

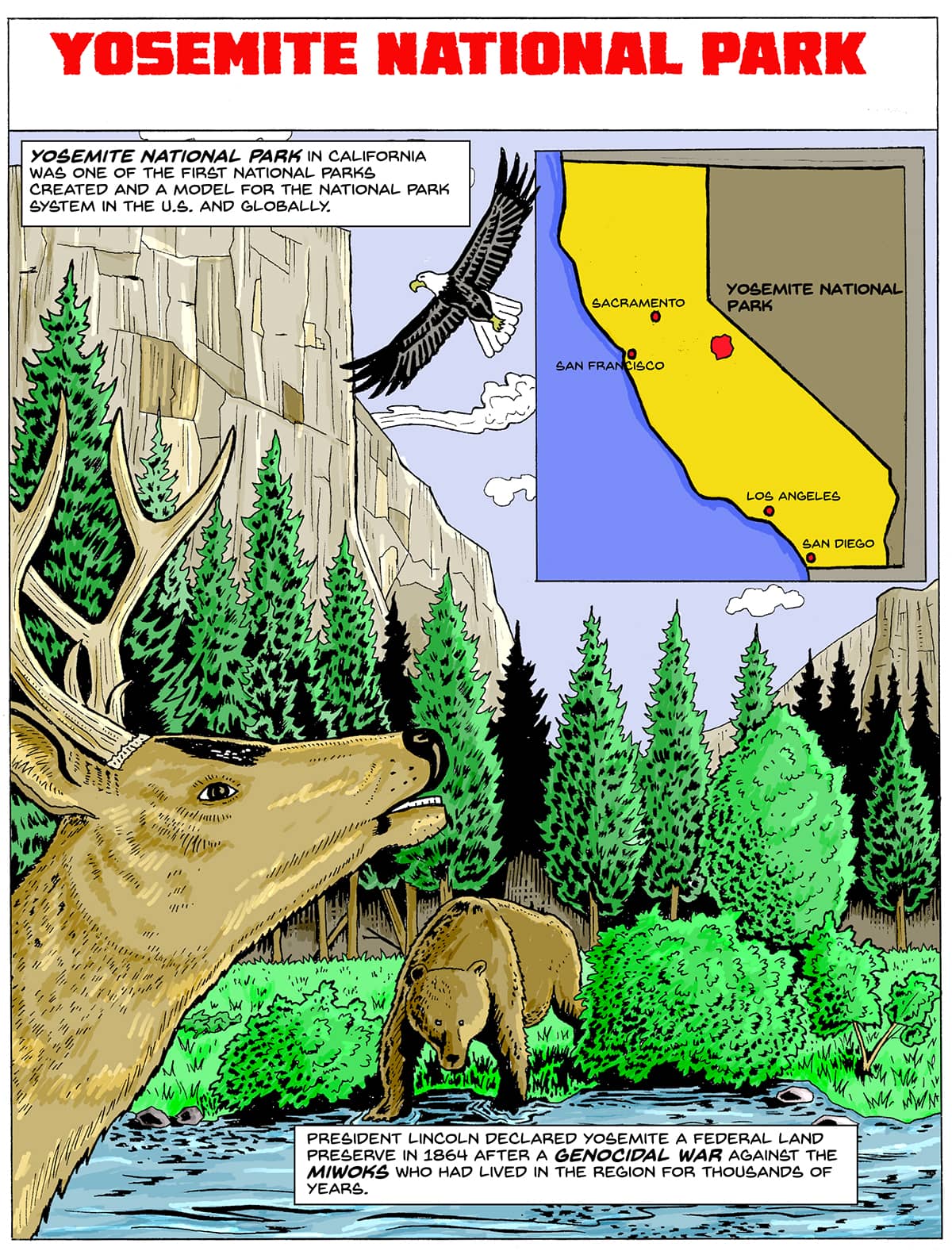

Yosemite National Park in California was one of the first national parks created and a model for the national park system in the U.S. and globally.

President Lincoln declared Yosemite a federal land preserve in 1864 after a genocidal war against the Miwoks who had lived in the region for thousands of years.

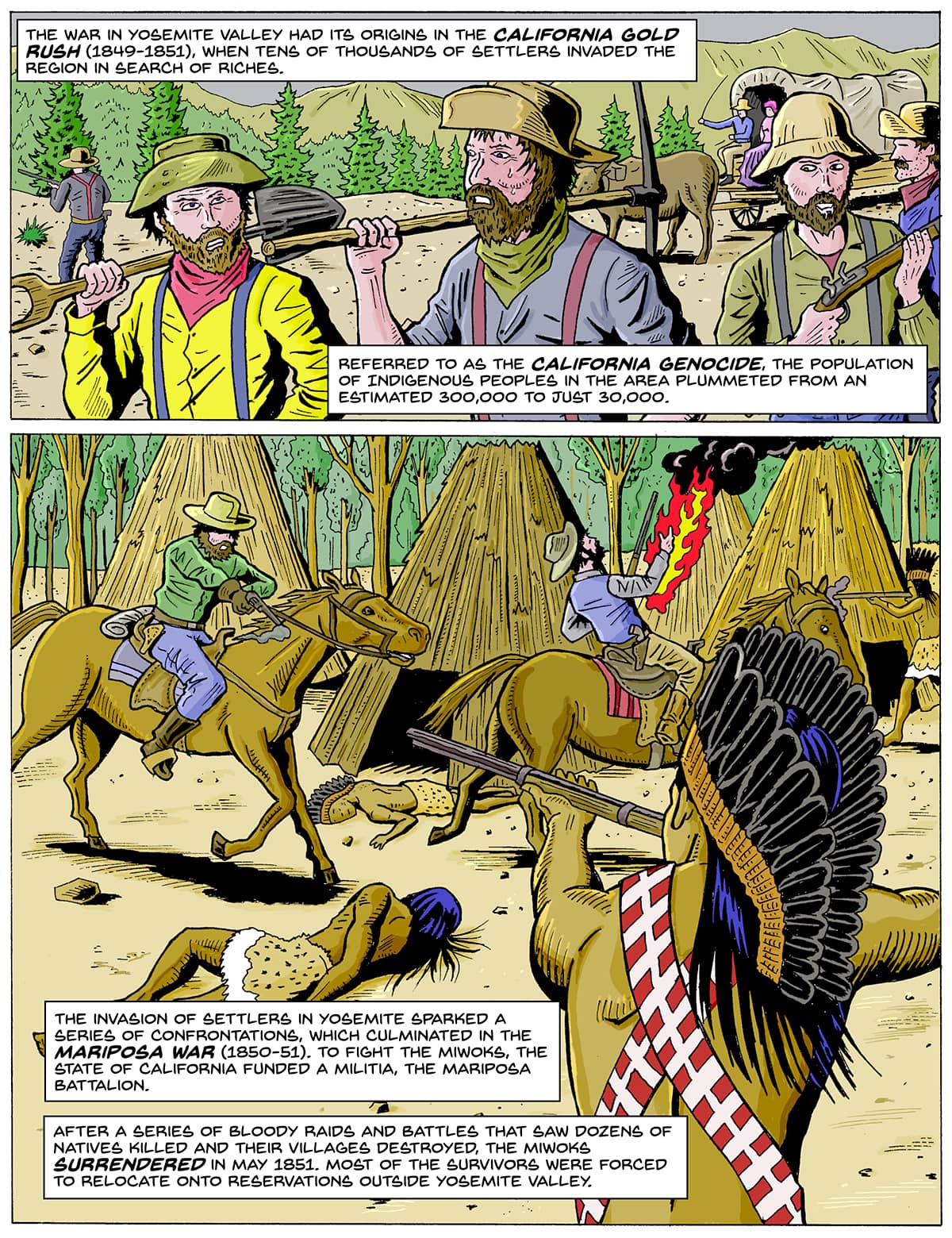

The war in Yosemite Valley had its origins in the California Gold Rush (1849-1851), when tens of thousands of settlers invaded the region in search of riches. Referred to as the California Genocide, the population of Indigenous peoples in the area plummeted from an estimated 300,000 to just 30,000.

The invasion of settlers in Yosemite sparked a series of confrontations, which culminated in the Mariposa War (1850-51). To fight the Miwoks, the state of California funded a militia, the Mariposa Battalion.

After a series of bloody raids and battles that saw dozens of Natives killed and their villages destroyed, the Miwoks surrendered in May 1851. Most of the survivors were forced to relocate onto reservations outside Yosemite Valley.

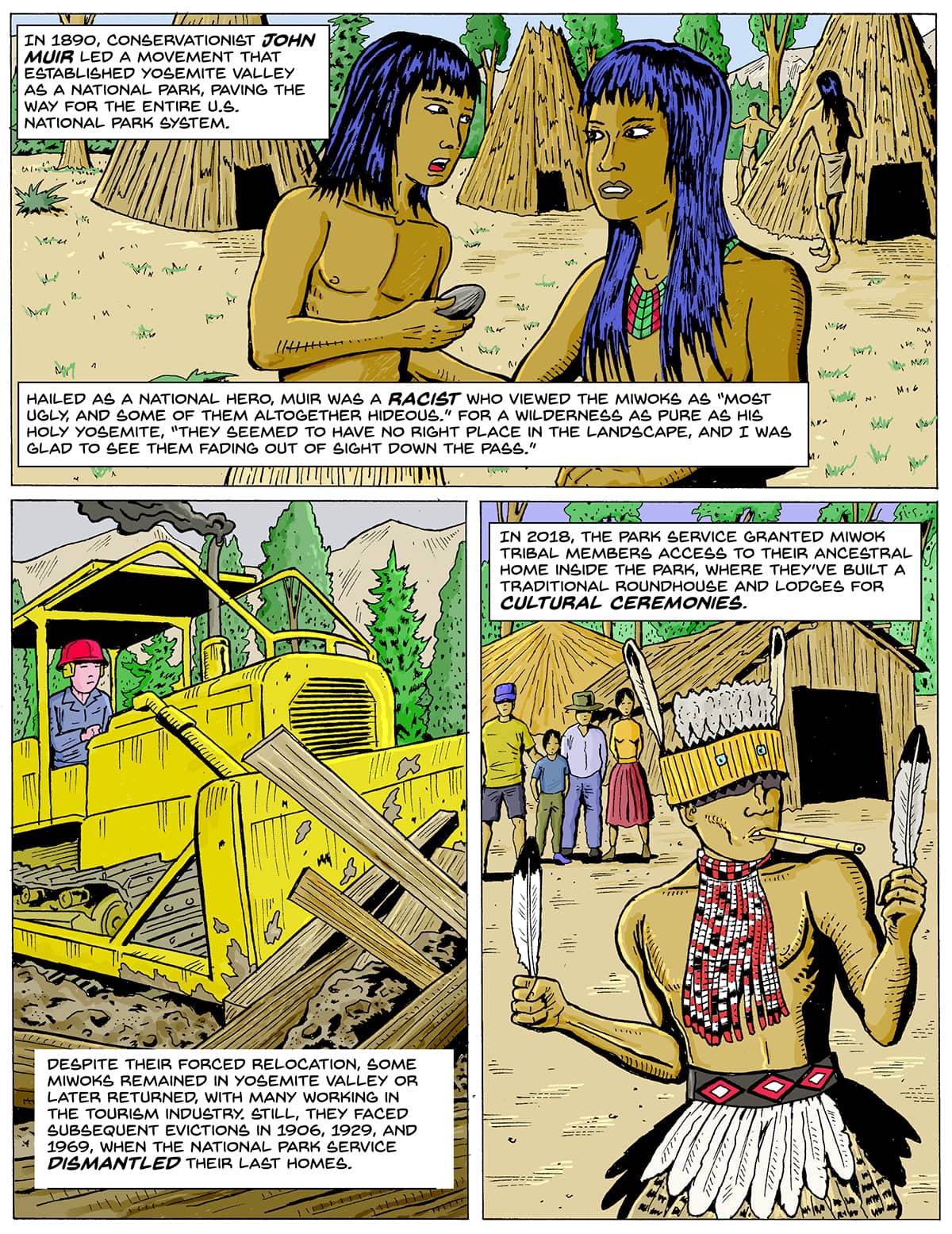

In 1890, conservationist John Muir led a movement that established Yosemite Valley as a national park, paving the way for the entire U.S. national park system. Hailed as a national hero, Muir was a racist who viewed the Miwoks as “most ugly, and some of them altogether hideous.” For a wilderness as pure as his holy Yosemite, “they seemed to have no right place in the landscape, and I was glad to see them fading out of sight down the pass.”

Despite their forced relocation, some Miwoks remained in Yosemite Valley or later returned, with many working in the tourism industry. Still, they faced subsequent evictions in 1906, 1929, and 1969, when the National Park Service dismantled their last homes.

In 2018, the park service granted Miwok tribal members access to their ancestral home inside the park, where they’ve built a traditional roundhouse and lodges for cultural ceremonies.

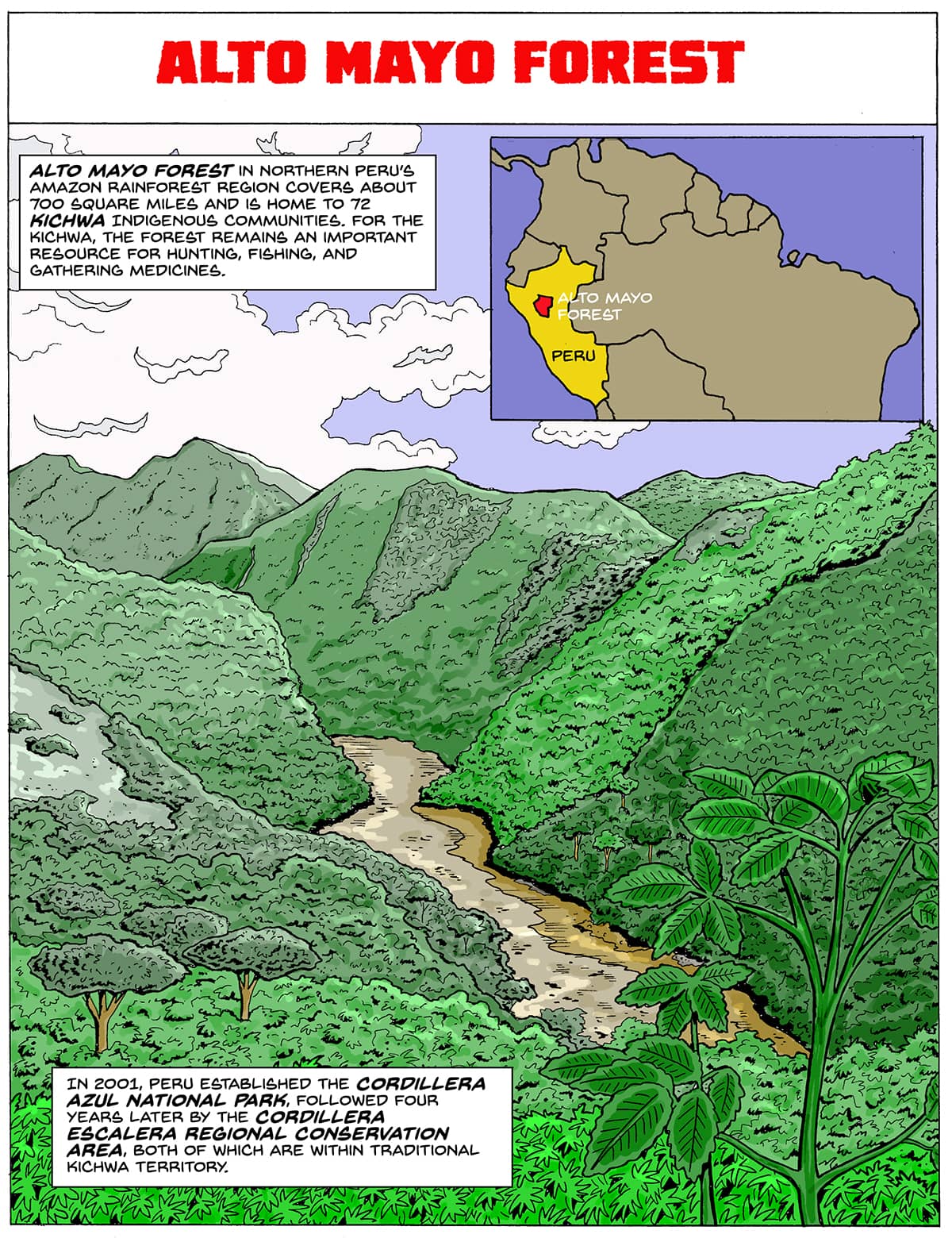

Alto Mayo forest

Alto Mayo forest in Northern Peru’s Amazon rainforest region covers about 700 square miles and is home to 72 Kichwa Indigenous communities. For the Kichwa, the forest remains an important resource for hunting, fishing, and gathering medicines.

In 2001, Peru established the Cordillera Azul National Park, followed four years later by the Cordillera Escalera Regional Conservation Area, both of which are within traditional Kichwa territory.

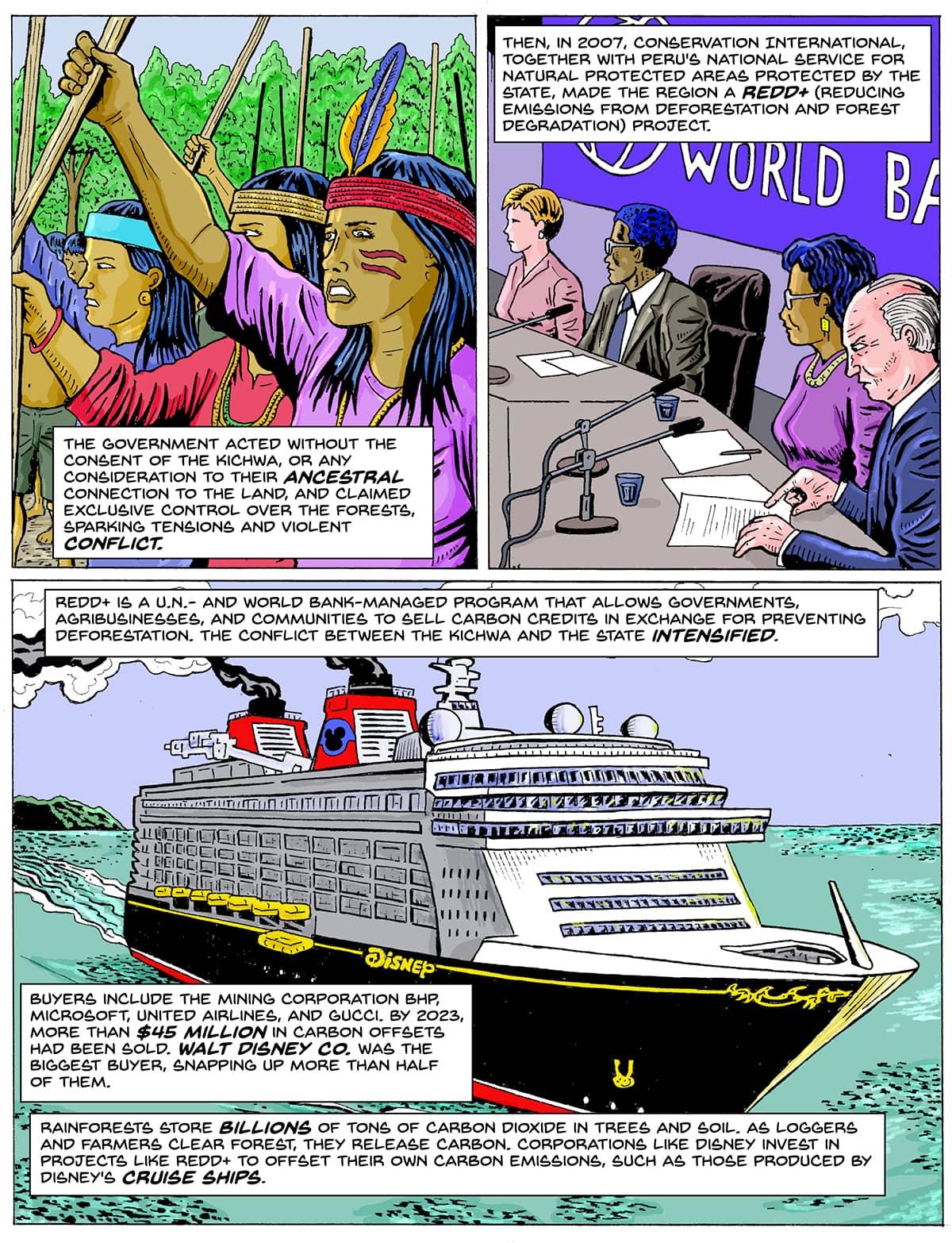

The government acted without the consent of the Kichwa, or any consideration to their ancestral connection to the land, and claimed exclusive control over the forests, sparking tensions and violent conflict.

Then, in 2007, Conservation International, together with Peru’s National Service for Natural Protected Areas Protected by the State, made the region a REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation) project.

REDD+ is a U.N.- and World Bank-managed program that allows governments, agribusinesses, and communities to sell carbon credits in exchange for preventing deforestation. The conflict between the Kichwa and the state intensified.

Buyers include the mining corporation BHP, Microsoft, United Airlines, and Gucci. By 2023, more than $45 million in carbon offsets had been sold. Walt Disney Co. was the biggest buyer, snapping up more than half of them.

Rainforests store billions of tons of carbon dioxide in trees and soil. As loggers and farmers clear forest, they release carbon. Corporations like Disney invest in projects like REDD+ to offset their own carbon emissions, such as those produced by Disney’s cruise ships.

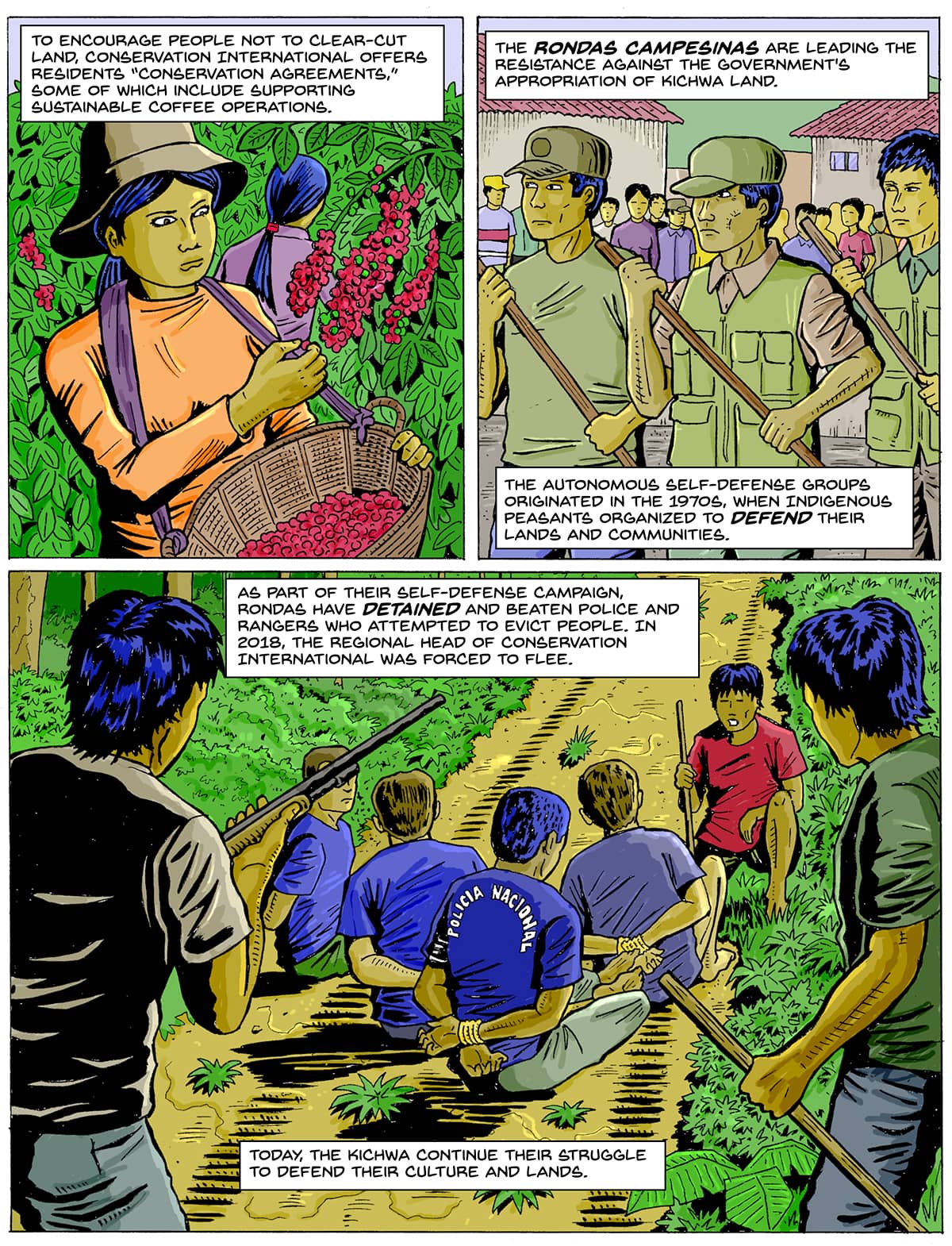

To encourage people not to clear-cut land, Conservation International offers residents “conservation agreements,” some of which include supporting sustainable coffee operations.

The rondas campesinas are leading the resistance against the government’s appropriation of Kichwa land. The autonomous self-defense groups originated in the 1970s, when Indigenous peasants organized to defend their lands and communities.

As part of their self-defense campaign, rondas have detained and beaten police and rangers who attempted to evict people. In 2018, the regional head of Conservation International was forced to flee.

Today, the Kichwa continue their struggle to defend their culture and lands.

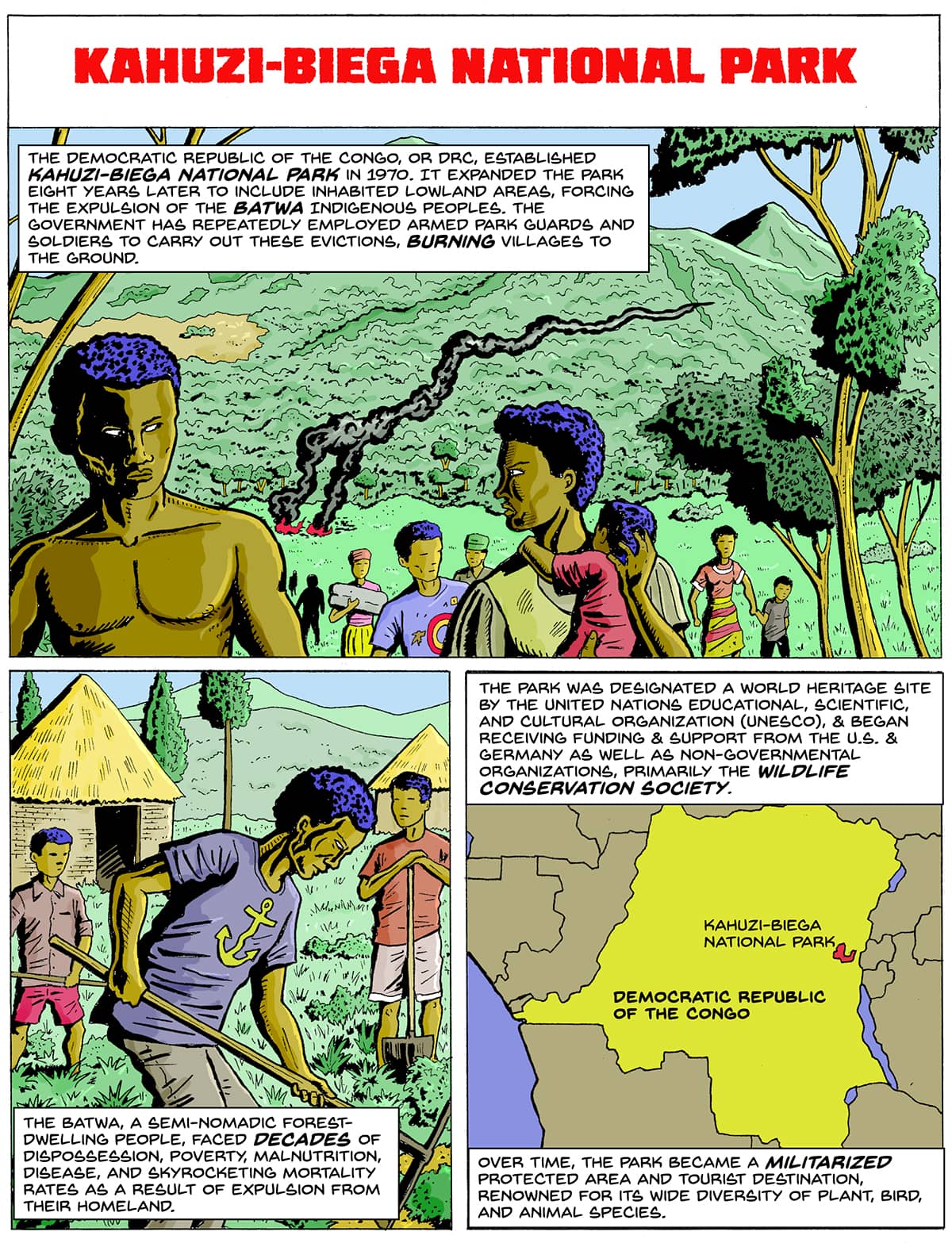

Kahuzi-Biega National Park

The Democratic Republic of the Congo, or DRC, established Kahuzi-Biega National Park in 1970. It expanded the park eight years later to include inhabited lowland areas, forcing the expulsion of the Batwa Indigenous peoples. The government has repeatedly employed armed park guards and soldiers to carry out these evictions, burning villages to the ground.

The Batwa, a semi-nomadic forest-dwelling people, faced decades of dispossession, poverty, malnutrition, disease, and skyrocketing mortality rates as a result of expulsion from their homeland.

The park was designated a World Heritage Site by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, or UNESCO, and began receiving funding and support from the U.S. and Germany as well as non-governmental organizations, primarily the Wildlife Conservation Society.

Over time, the park became a militarized protected area and tourist destination, renowned for its wide diversity of plant, bird, and animal species.

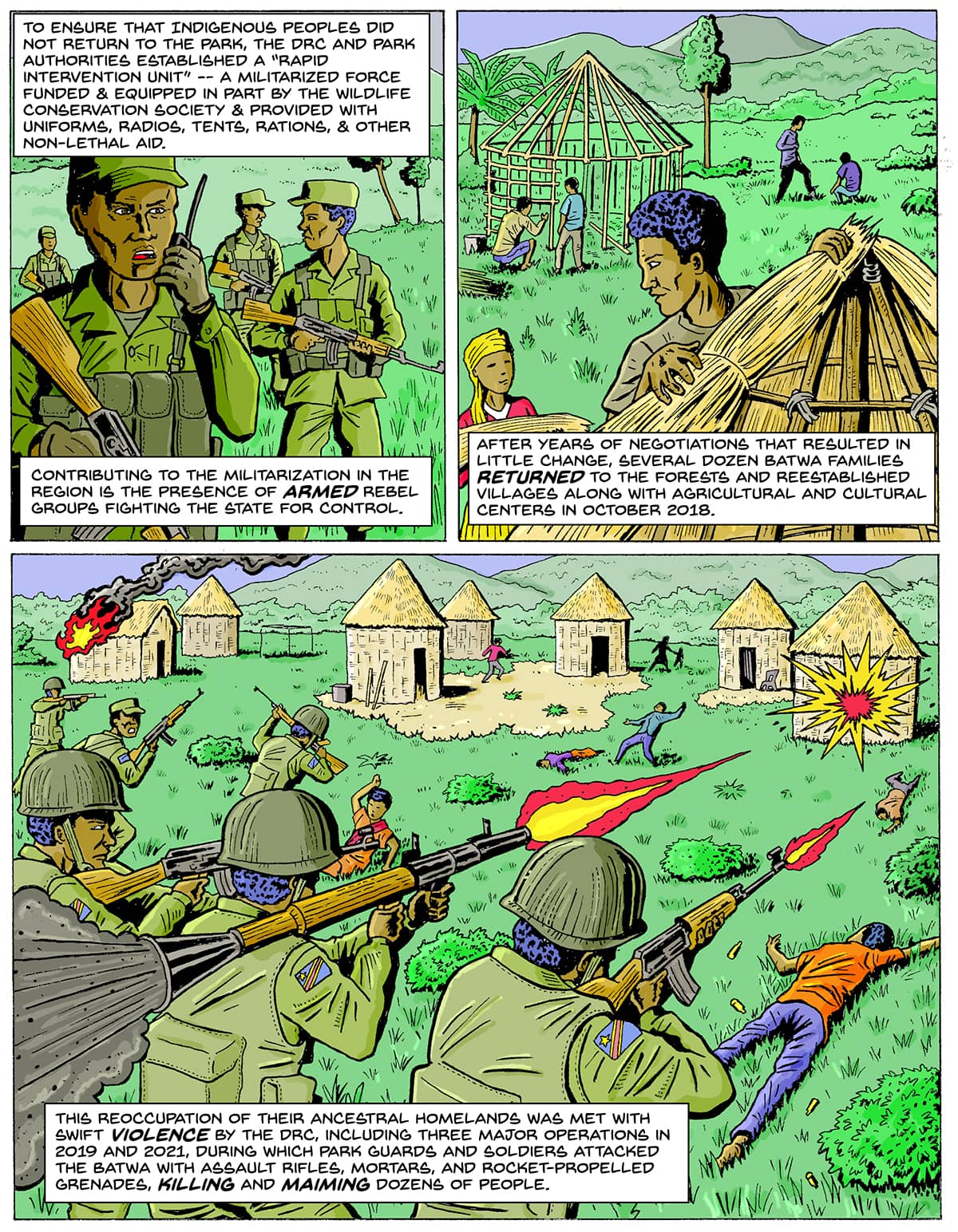

To ensure that Indigenous peoples did not return to the park, the DRC and park authorities established a “rapid intervention unit” — a militarized force funded and equipped in part by the Wildlife Conservation Society and provided with uniforms, radios, tents, rations, and other non-lethal aid.

Contributing to the militarization in the region is the presence of armed rebel groups fighting the state for control.

After years of negotiations that resulted in little change, several dozen Batwa families returned to the forests and reestablished villages along with agricultural and cultural centers in October 2018.

This reoccupation of their ancestral homelands was met with swift violence by the DRC, including three major operations in 2019 and 2021, during which park guards and soldiers attacked the Batwa with assault rifles, mortars, and rocket-propelled grenades, killing and maiming dozens of people.

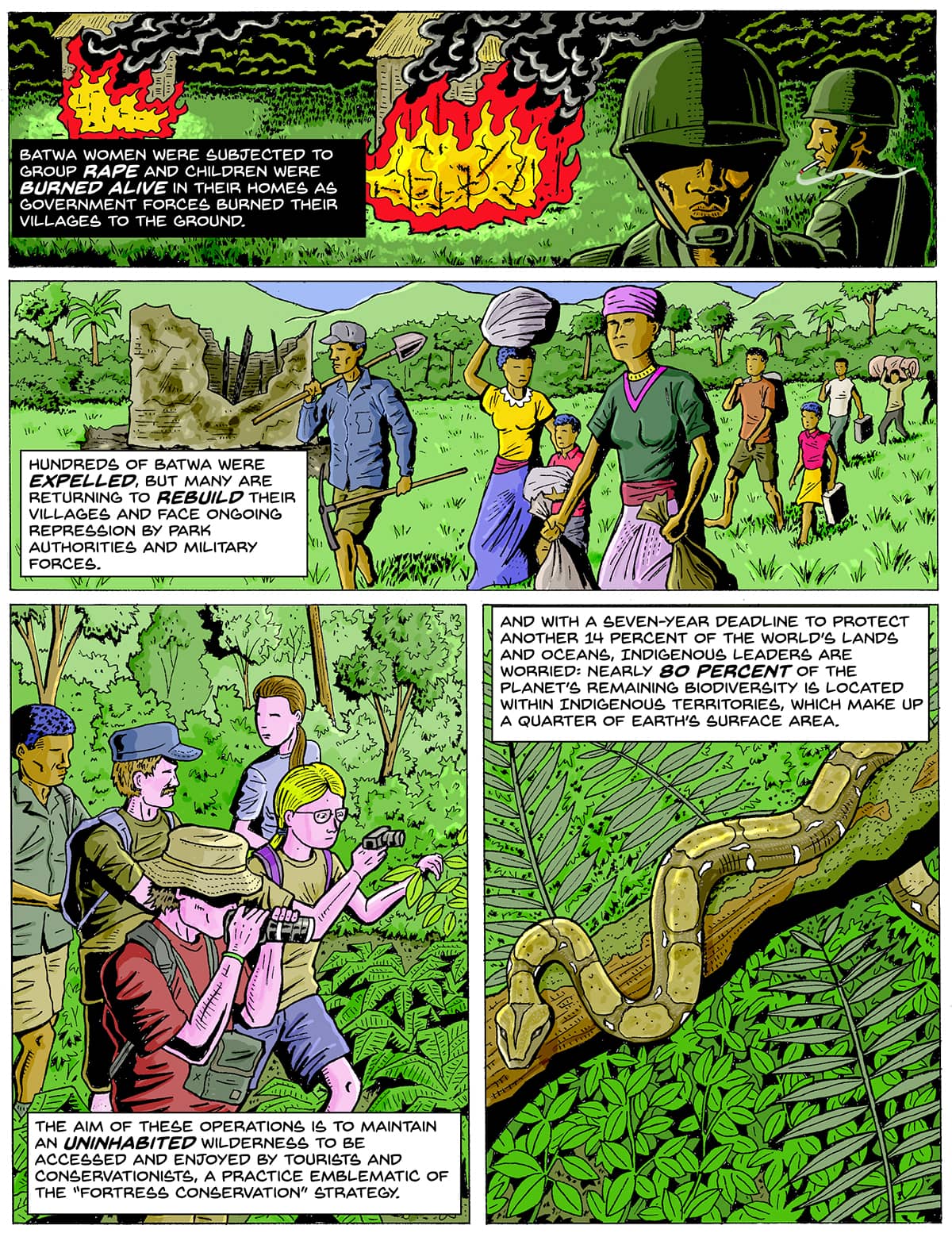

Batwa women were subjected to group rape and children were burned alive in their homes as government forces burned their villages to the ground.

Hundreds of Batwa were expelled, but many are returning to rebuild their villages and face ongoing repression by park authorities and military forces.

The aim of these operations is to maintain an uninhabited wilderness to be accessed and enjoyed by tourists and conservationists, a practice emblematic of the “fortress conservation” strategy.

And with a seven-year deadline to protect another 14 percent of the world’s lands and oceans, Indigenous leaders are worried: Nearly 80 percent of the planet’s remaining biodiversity is located within Indigenous territories, which make up a quarter of Earth’s surface area.

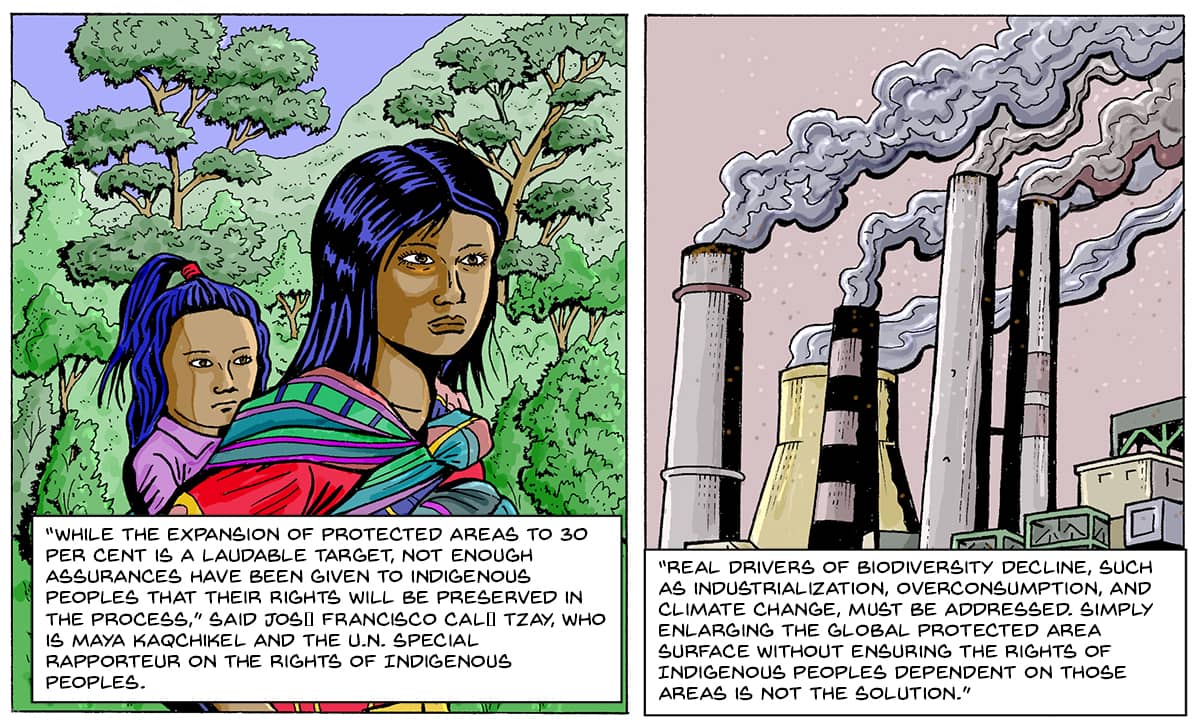

“While the expansion of protected areas to 30 per cent is a laudable target, not enough assurances have been given so far to indigenous peoples that their rights will be preserved in the process,” said José Francisco Calí Tzay, who is Maya Kaqchikel and the U.N. Special Rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples.

“Real drivers of biodiversity decline, such as industrialization, overconsumption, and climate change, must be addressed. Simply enlarging the global protected area surface without ensuring the rights of indigenous peoples dependent on those areas is not the solution.”

Download a PDF of Fortress Conservation: A Legacy of Violence.

Author and artist: Gord Hill is the author of two graphic novels, The 500 Years of Resistance Comic Book and The Anti-Capitalist Resistance Comic Book. He is a member of the Kwakwaka’wakw nation whose territory is located on northern Vancouver Island and adjacent mainland in the province of British Columbia. He has been involved in Indigenous people’s and anti-globalization movements since 1990. He lives in Vancouver.

This project was supported by the Bay & Paul Foundations

- Editors: Tristan Ahtone & Chuck Squatriglia

- Researcher: Tushar Khurana

- Copy editor: Kate Yoder

- Spanish translation: Nathalie Herrmann

- French translation: Leah Powers

- Additional art direction: Mignon Khargie

License: ©2023 Grist

Interested in republishing this story? Please reach out to syndication@grist.org.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How protecting the Earth became an excuse for murder on Apr 12, 2023.

This content originally appeared on Grist and was authored by Gord Hill.

Gord Hill | Radio Free (2023-04-12T10:45:00+00:00) How protecting the Earth became an excuse for murder. Retrieved from https://grist.org/indigenous/fortress-conservation-legacy-violence-comic-indigenous-land-30x30/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.