Since the brutal police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis in 2020, and the Black Lives Matter protests that spread across the country, how have news media covered issues of policing policy and police reform?

To offer perspective on this question, FAIR looked at which kinds of sources have been most prominent in the New York Times‘ coverage of these issues, and therefore are given the most power to shape the narrative. We compared three time periods: June 2020, when the BLM protests were at their height; May–June 2022, leading up to and encompassing the two-year anniversary of those protests; and mid-January to mid-February 2023, when the police killing of Tyre Nichols was prominent in news coverage and reignited conversations around police reform.

We found that, overall, the Times leaned most heavily on official (government and law enforcement) sources when reporting on the issue of policing policy—giving the biggest platform to the targets of reform, rather than the people who would most benefit from it. We also found a prominent stress on party politics and a lack of racial and gender diversity among sources.

However, we also found that the Times‘ 2023 Tyre Nichols coverage offered a wider diversity of sources, and a greater percentage of Black sources, than in the previous time periods. This appeared to result in part from many of the articles focusing on deeper reporting on the local situation in Memphis, a majority-Black city (unlike, for instance, Minneapolis, where George Floyd was killed).

In contrast, the 2022 articles focused more on policing and crime as an election topic at a national level. The 2020 articles covered the broadest range of issues and geography, but with particular attention to the protests, and the federal and local legislative responses.

The most recent coverage had more voices critical of policing policy and practices than in the previous study periods—though, at the same time, those voices came less from protests on the streets and more from advocacy groups, lawyers, academics, religious leaders and general public sources, and so shifted from the raw anger and “defund the police” demands of 2020 to less radical accountability measures.

Methodology

Eliminating passing mentions and opinion pieces, we examined New York Times news articles centrally about policing policy or reform. We found 10 articles (with 58 sources) meeting our criteria between May 1 and June 30, 2022, and 16 articles (111 sources) between January 13 and February 10, 2023 (two weeks before and after the main day of the Tyre Nichols protests). Because the Times covered the issue so extensively in 2020, we took a random sample of 25 articles (142 sources) meeting our criteria from June 2020.

Sources were coded for occupation, gender, race/ethnicity and party affiliation (for government officials and politicians). Each source could receive more than one code for occupation (e.g., academic and former law enforcement) and race/ethnicity (e.g., Black and Asian American).

The racial binary

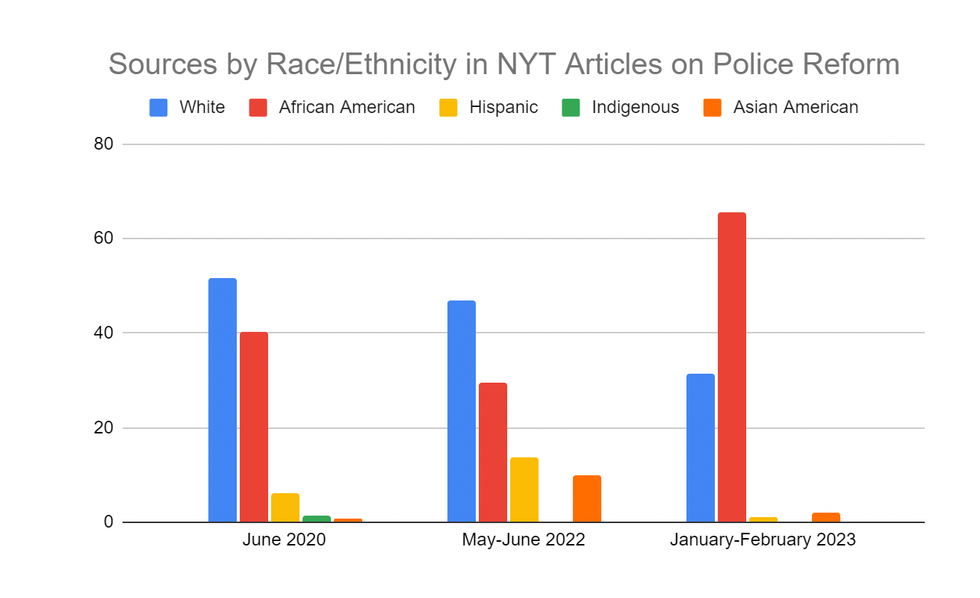

The movement to protest racist policing has been led primarily by Black activists, many of them women. It is a movement fundamentally about race, racism and white supremacy. Yet white sources handily outnumbered Black sources in coverage of police reform in two of the three periods studied, and men outnumbered women by roughly three-to-one in all three.

Of sources whose race could be identified, 52% were white and 40% Black in the 2020 data. In the 2022 data, white sources decreased slightly, but dominated Black sources by an even greater margin: 48% to 30%.

In the 2023 data, that trend reversed, and Black sources reached 66%, while white sources dropped to 31%.

One thing that didn’t change across the time periods was the New York Times‘ reliance on male sources: Men were 72% of sources with an identifiable gender in 2020, 74% in 2022 and 76% in 2023.

Policing is not a strictly Black-and-white issue, of course, and the coverage played out against the backdrop of rising xenophobia and anti-Asian hate resulting from the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, with many using rising bias crimes against people perceived as Asian as an excuse to increase policing. Yet such voices were largely excluded from the conversation at the Times.

In 2020, 6% of sources were Hispanic and 2% were Indigenous; 1% were Asian-American and none were of Middle Eastern descent. In 2022, Times sources expanded a bit from the racial binary, with 14% Hispanic sources and 10% Asian-American. (No Indigenous sources or sources of Middle Eastern descent were quoted in 2022.) In 2023, that diversity disappeared, and of the 99 sources with identifiable race/ethnicity, only 2% were of Asian descent and 1% were Hispanic; none were of Indigenous or Middle Eastern descent.

Government knows best?

The bias toward white and male sources—and the decrease in white sources in 2023—can be explained partly by the New York Times‘ bias toward government and law enforcement sources, both of which are disproportionately white, male fields.

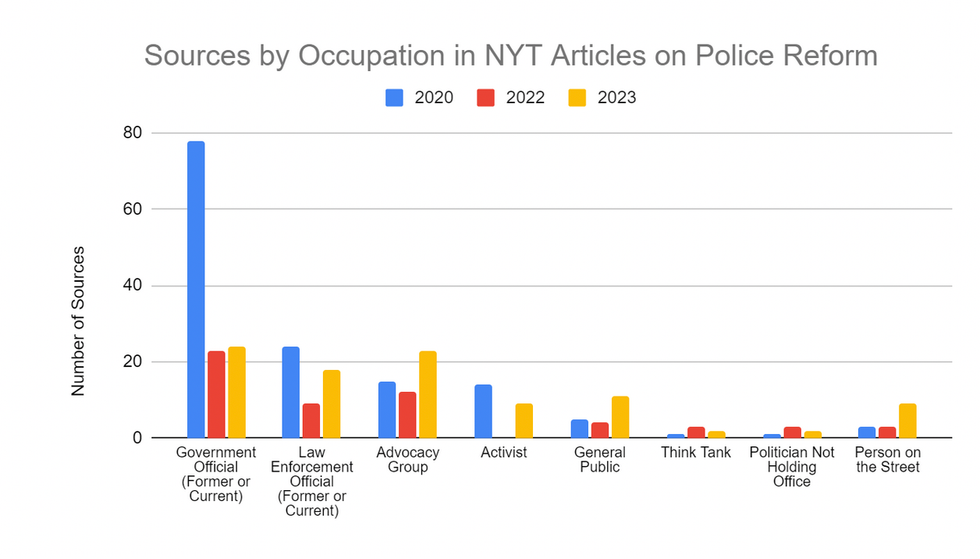

In June 2020, a majority of all sources (55%) were current or former government officials—not including law enforcement, which formed the second-largest share of sources quoted, at 17%. Two years later, government sources had dropped to 40%, while law enforcement stayed roughly the same, at 16%; politicians running for office increased from less than 1% of 2020 sources to 5% of 2022 sources. In 2023, government sources dropped yet again, to only 22% of sources, and law enforcement remained steady at 16%.

Meanwhile, activists (protesters or organizers) accounted for 10% of 2020 sources, and representatives of professional advocacy groups accounted for 11%. In 2022, when street protests were relatively much smaller compared to 2020, activist voices were missing entirely, and professional advocate sources—such as the president of the NAACP and the director of Smart Justice California—increased to 21%. In 2023, the total across these two groups increased, with advocates accounting for 21% of sources and activists for 9%, and a greater number of non-governmental sources such as lawyers, academics and religious leaders appeared than in the previous time periods.

Combined, more than 7 in 10 of all sources quoted in 2020, more than 5 in 10 in 2022, and nearly 4 in 10 in 2023 were the government and law enforcement officials the protests sought to hold accountable. Only about 2 in 10 in 2020 and 2022, and 3 in 10 in 2023, were civil society members protesting or advocating for (or, in some cases, against) reform.

The proportion of white sources in these stories was high among law-enforcement sources (54% in 2020, 67% in 2022, 56% in 2023) and, less uniformly, among government sources (54% in 2020, 39% in 2022, 33% in 2023). Black sources were represented most among activists (79% in 2020, 89% in 2023) and advocates (20% in 2020, 58% in 2022, 52% in 2023).

In 2020 and 2022, women were likewise better represented among activists and advocates than among government and law enforcement sources. In 2020, 47% of advocate sources and 36% of activist sources were female, as compared to 22% of government and 17% of law enforcement sources. In 2022, 50% of advocates were female, compared to 13% of government and 22% of law enforcement sources.

In 2023, however, female government sources rose to 38%, a higher proportion of women in that year than among advocates (17%) or activists (29%). (Law enforcement sources continued to be a low 17% women.)

The increases in racial and ethnic diversity from 2020 to 2022 came largely within government sources, with officials quoted including the Black mayor of New York City, Eric Adams; Asian-American House representatives Pramila Jayapal and Ro Khanna; and Hispanic legislators Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Sen. Ted Cruz.

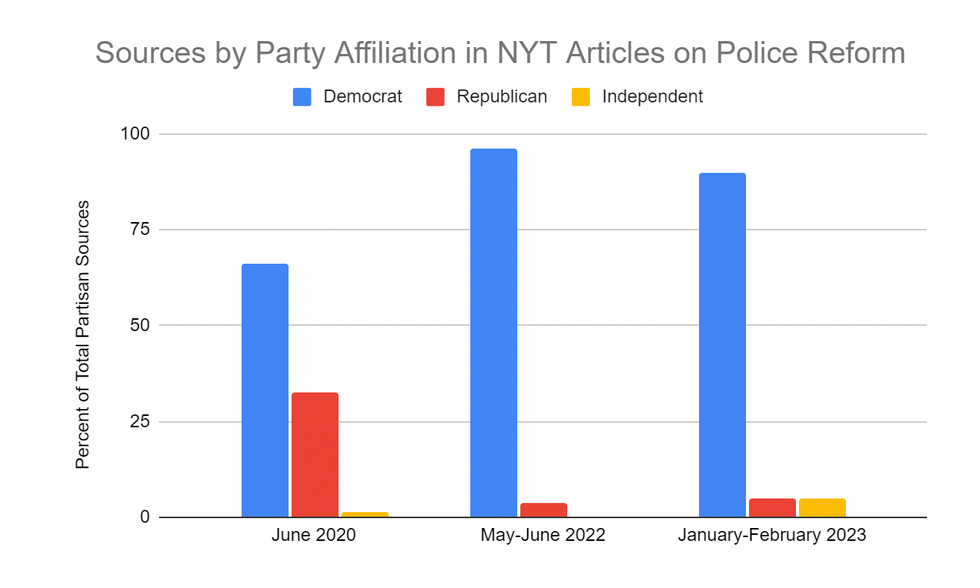

This diversification of government sources happened along with a shift in partisanship of sources: While Democrats dominated the conversation in 2020, with 51 sources to Republicans’ 25, Republicans were almost entirely absent in 2022, with a single source (Cruz) to Democrats’ 25. The absence of Republican sources continued in 2023, when 18 of 20 sources with party affiliations were Democrats, and one was an independent.

This near-total absence of Republicans from the conversation reflects in part the switch in power at the national level; Republicans controlled both the White House and Senate in 2020, and both had flipped to the Democrats by 2022. It also reflects the reality that the massive nature of the protests forced Republicans to address the issue of police reform in 2020, but they were no longer talking about it much in 2022—nor were outlets like the New York Times forcing them to.

Shift in sources

The striking shift in the race of sources in the 2023 time period is not only about the decrease in government sources; it appears to be partly due to the focus on Memphis, where nearly two-thirds of residents and more than half of the police force (including its police chief, and all five of the officers charged with the murder of Nichols) are Black.

In one front-page article (2/5/23) that focused on the “Scorpion” unit that killed Tyre Nichols, headlined “Memphis Unit Driven by Fists and Violence,” a team of six Times reporters quoted 15 different sources, eight of whom were either victims of the unit or family members of victims; all victims and family members were Black. (These were coded as “General Public”: people without a particular professional or activist affiliation, but with experience relevant to the subject they are speaking on.) Only three of the total sources were government officials, and none were law enforcement.

Some articles not exclusively about the Nichols killing still focused on race. “Officers’ Race Turns Focus to System” (1/29/23) featured 14 sources across an array of nine different types of occupations; none were current or former government, and 11 were Black.

The focus on the Tyre Nichols killing also translated at the Times into more of a focus on police accountability, compared with coverage that did not center on police killings. In the absence of a police killing, an article (1/27/23) focused on policing policy appeared under the print-edition headline, “Heavier Police Presence Sees Success as Crime Drops in New York Subways.” It featured four New York government officials, two of whom touted increased policing. Only one advocate questioned those officials, calling for more frequent subway and bus service as an alternative form of public safety. The headline reflects whose narrative was given more credence by the Times.

That such an article so credulous of increased policing, and so light on critical sources, could appear against the backdrop of the Tyre Nichols story illustrates the blinkered nature of the Times‘ improved coverage. While high-profile incidents of police violence might narrowly prompt more critical coverage, systemic shifts in reporting face an uphill battle against corporate media’s longstanding reliance on and trust in government and law enforcement sources to establish the narrative on policing.

From ‘defund’ to party politics to reform

In 2020, when protests against police violence erupted across the country, the New York Times covered issues of policing policy and reform with a heavy tilt toward government and law-enforcement sources, and toward white sources.

Activists voicing their grievances against racist, violent policing, and making demands that such policing be rethought in more radical ways, occasionally found their way into the paper of record. Black Futures Lab’s Alicia Garza, for example, was quoted by the Times (6/21/20): “The continual push to shield the police from responsibility helps explain why a lot of people feel now that the police can’t be reformed.”

But their voices were largely drowned out by government officials, many of whom wanted nothing more than to make the protests go away, like Minneapolis city council member Steve Fletcher (6/5/20):

It’s very easy as an activist to call for the abolishment of the police. It is a heavier decision when you realize that it’s your constituents that are going to be the victims of crime you can’t respond to if you dismantle that without an alternative.

In letting government sources dominate again in 2022, Times coverage turned primarily to party politics, rather than investigations into whether reforms had been enacted, and whether or how police tactics had changed. The idea of defunding the police shifted from being presented as a concept to be debated to little more than a political punching bag, with law enforcement sources like former New York police commissioner Bill Bratton (6/9/22) calling the Defund movement “toxic.” Most Democrats distanced themselves from the movement, as when Joe Biden (5/31/22) was quoted: “We should all agree the answer is not to defund the police. It’s to fund the police. Fund them. Fund them.”

When Tyre Nichols was killed by police in 2023, it was not against a backdrop of an election season, nor did it spark protests at the scale of 2020. This time, Times coverage dug a bit deeper at the local level, turning to a wider variety of sources, and resulting in a greater emphasis on the need for police accountability.

While at least one source (1/29/23) called for defunding the police, most critical voices called more generally for accountability, and expressed frustration at the lack of any effective reforms since 2020. For instance, in an article headlined “Many Efforts at Police Reform Remain Stalled” (2/9/23), the president of the NAACP was quoted: “Far too many Black people have lost their lives due to police violence, and yet I cannot name a single law that has been passed to address this issue.”

The shift to a more diverse set of sources on the issue at the Times, during this one-month time period, is commendable. While the circumstances and location of Tyre Nichols’ killing offered strong opportunities to bring in more Black sources, the Times could easily have fallen back on its usual reliance on official sources, as it did in 2020 and 2022. Now it’s incumbent upon the Times to apply that more diverse and critical approach across all policing stories—not only when similarly high-profile police killings rock the country.

This content originally appeared on Common Dreams and was authored by Julie Hollar.

Julie Hollar | Radio Free (2023-04-30T13:33:17+00:00) Who Gets to Talk About Police Reform?. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2023/04/30/who-gets-to-talk-about-police-reform/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.