On the night of December 23, 1975, Ron Estes, the CIA’s deputy station chief in Athens, was lounging on the couch in his girlfriend’s apartment when the man who worked as a driver for his boss, Richard Welch, burst through the front door.

“A shooting, and Mr. Welch is down,” the driver yelled.

Estes grabbed his coat and ran outside, ignoring his girlfriend’s pleas to stay.

At Welch’s house in the Greek capital, Estes saw the station chief lying on his back on the sidewalk, his wife, Kika, kneeling beside him. Blood covered Welch’s face, and Estes could see immediately that he was dead. “I didn’t need to feel for a pulse,” he said in an interview. A police car arrived, and Estes asked the officer to call an ambulance. When no ambulance arrived, they hauled the body into Welch’s car and Estes and Welch’s driver followed the police officer, siren blaring and lights flashing, through the streets of Athens to the nearest hospital. A medical team was waiting; they quickly placed Welch on a gurney and took him to an examining room. There, a doctor placed a stethoscope on Welch’s chest and confirmed to Estes that he was dead.

Welch was 46 years old. A career CIA officer, he had been the CIA’s Athens station chief for six months.

At the hospital, Welch’s driver finally caught his breath and told Estes what had happened. He had driven Welch and his wife home from a Christmas party at the U.S. ambassador’s residence, then stopped in front of the walled compound that enclosed Welch’s house to open the front gates. As Welch and his wife got out, three armed men in a black car pulled up behind them, burst out of the car, and confronted Welch.

“Put your hands up!” one of the men told Welch in Greek.

“What?” Welch asked in English.

One of the gunmen leveled his .45 caliber handgun and fired three times. An autopsy later showed that the first shot hit Welch in the chest, rupturing his aorta and killing him instantly. The three men got back in their car and sped away. That’s when Welch’s driver rushed to get Estes.

The hospital lobby soon filled with journalists, who had most likely heard about the shooting by monitoring the city’s police radio. Estes realized that many of them already seemed to know that Welch had been the CIA’s station chief. Steven Roberts, a New York Times reporter in Athens who covered Welch’s murder, wrote the next day that he had been talking with Welch at the ambassador’s Christmas party an hour before the shooting.

A spokesperson from the U.S. Embassy arrived, and Estes slipped away from the crowd of reporters. The police found the gunmen’s car, which had been stolen, abandoned several blocks from Welch’s home.

Back at the CIA station, Estes sent cables to CIA headquarters and talked on a secure phone with a top agency official. “When I finished briefing him, he said, ‘I could only hear about half of what you said.’” Estes recalled. “‘Send me a cable repeating what you said immediately. We’ve got to go to the president.’”

An undated photograph of Athens station chief Richard Welch before his death in 1975.

Photo: The Boston Globe, 1975

Before the Church Committee was created in January 1975, there had been no real congressional oversight of the CIA. The House and Senate Intelligence Committees did not yet exist, and the Church Committee’s unprecedented investigation marked the first effort by Congress to unearth decades of abusive and illegal acts secretly committed by the CIA — and to curb its power.

Sen. Frank Church, the liberal Democrat from Idaho who chaired the committee, had come to believe that the future of American democracy was threatened by the rise of a permanent and largely unaccountable national security state, and he sensed that at the heart of that secret government was a lawless intelligence community. Church was convinced it had to be reined in to save the nation.

The Church Committee’s unprecedented investigation marked the first effort by Congress to unearth decades of abusive and illegal acts secretly committed by the CIA — and to curb its power.

To a great degree, he succeeded. By disclosing a series of shocking abuses of power and spearheading wide-ranging reforms, Church and his Committee created rules of the road for the intelligence community that largely remain in place today. More than anyone else in American history, Church is responsible for bringing the CIA, the FBI, the National Security Agency, and the rest of the government’s intelligence apparatus under the rule of law.

But first, Church and his committee had to withstand a brutal counterattack launched by a Republican White House and the CIA, both of which wanted to blunt Church’s reform efforts. The White House and CIA quickly realized that the Welch killing, which occurred just as the Church Committee was finishing its investigations and preparing its final report and recommendations for reform, could be used as a political weapon. President Gerald Ford’s White House and the agency falsely sought to blame the Church Committee for Welch’s murder, claiming, without any evidence, that its investigations had somehow exposed Welch’s identity and left him vulnerable to assassination.

There was absolutely no truth to the claims, but the disinformation campaign was effective. The Ford administration’s use of the Welch murder to discredit the Church Committee was a model of propaganda and disinformation; an internal CIA history later praised the “skillful steps” that the agency and the White House “took to exploit the Welch murder to U.S. intelligence benefit.”

The Welch case has long since served as a classic example of how to exploit and weaponize intelligence for political purposes. The George W. Bush administration’s efforts to justify the 2003 invasion of Iraq by claiming that Saddam Hussein was behind 9/11; the Republican obsession with the 2012 attack on the U.S. compound in Benghazi, Libya, and their use of it to discredit then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton; and Donald Trump’s efforts to portray himself as the victim of a “deep state” conspiracy can all be traced back to the way U.S. leaders exploited Welch’s 1975 killing.

The White House and CIA were aided in their propaganda campaign by the fact that Estes did not go public at the time with his account of what really happened in Athens. Now, nearly 50 years later, Estes has finally broken his silence. In interviews for my new book, “The Last Honest Man,” he talked in detail about the murder and its causes with a journalist for the first time, supplying new evidence that Welch’s assassination stemmed from the toxic politics of Athens — not Washington.

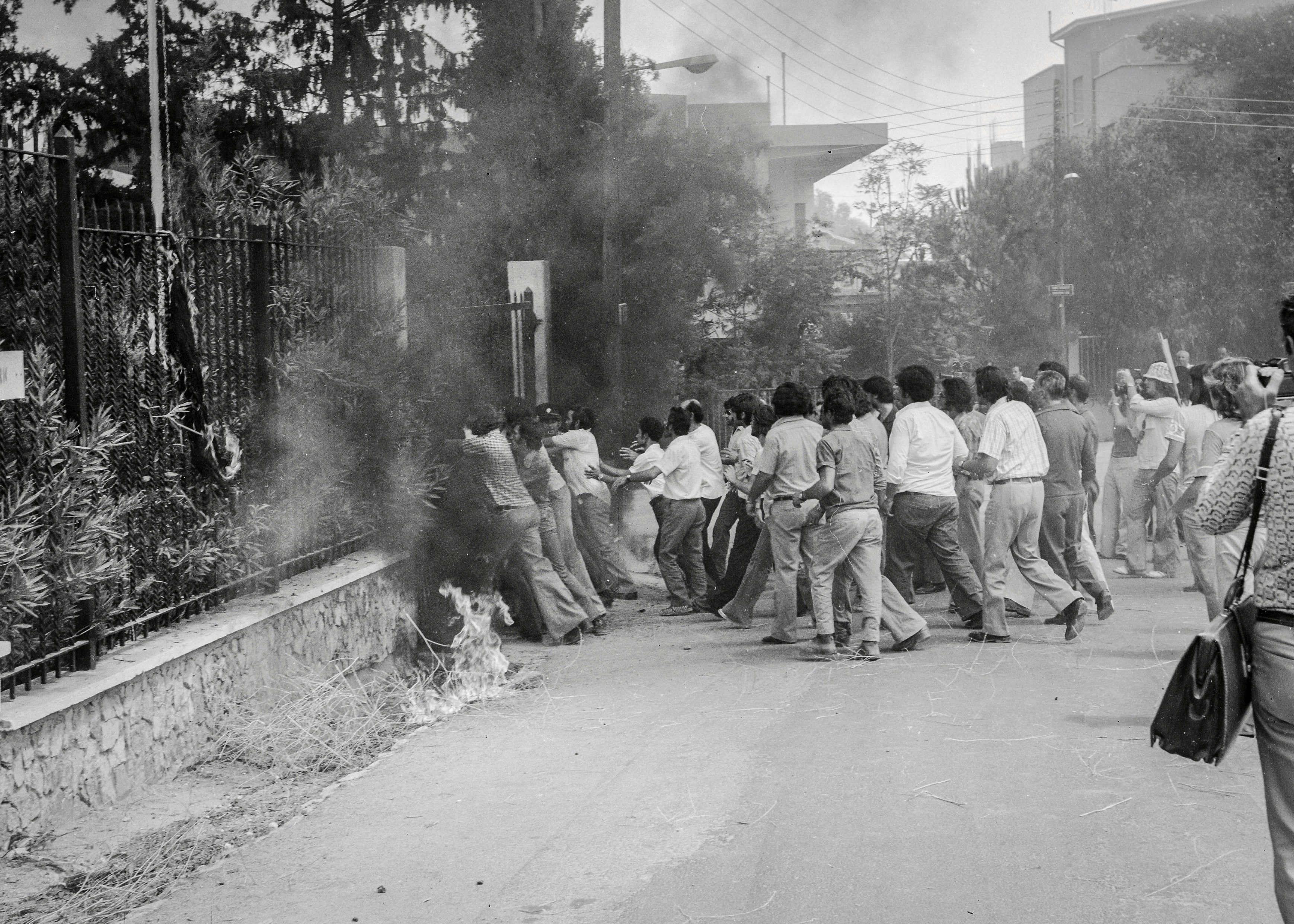

Photo: Bettmann Archive

Welch’s killing was a direct result of the feverish political climate that gripped Greece in the mid-1970s. In July 1974, the right-wing military junta that ruled Greece backed a coup in Cyprus to oust the island’s president and create a union between Greece and Cyprus. Making Cyprus fully Greek was a longtime objective of Greek right-wing ultranationalists, but the move immediately prompted a Turkish invasion of Cyprus. Greek junta leader Dimitris Ioannidis bitterly blamed the United States for not stopping the Turkish invasion.

Greek hostility toward the United States spread. On August 19, 1974, a pro-Greek mob attacked the U.S. embassy in Nicosia, Cyprus, and both U.S. Ambassador Rodger Davies and a local embassy employee were killed. After a ceasefire, Cyprus was divided into Greek and Turkish zones; the disastrous outcome of the coup in Cyprus later led to the collapse of the military junta in Athens. But anger in Greece toward the United States continued unabated.

The relationship between the CIA and Greece’s Central Intelligence Service, known as the KYP, was also poisoned. Soon, someone had leaked the names of Welch and a few other officers in the CIA’s Athens station to the Greek press.

In November 1975, Welch’s name and home address were published in English language and Greek language newspapers in Athens. The information “was obviously leaked by hostile KYP officers,” Estes said in the interview, “because the only names leaked were those in liaison contact with KYP.” (CIA overseas stations often included officers who were in liaison contact with the intelligence service of the local country — their identities as CIA officers thus declared to the service so they could meet with them and trade intelligence — and others who were not identified so they could spy without the knowledge of the local government.)

Welch was not hard to find; he lived in a luxurious villa that had been the official residence of the CIA station chief for decades. After his name and home address were published in the press, Estes talked to him about whether he should move. But Welch and Estes concluded that the threat was minimal. “We both agreed that political assassination was not part of the fabric of Greek history or culture,” Estes recalled.

It was a fatal miscalculation. Welch’s murder was carried out by a new, extremely violent Greek leftist guerrilla organization called 17 November. While right-wing Greek nationalists hated the United States for betraying Greece over Cyprus, left-wing Greeks blamed the United States for helping to install the military junta in Athens in 1967. The 17 November group was named for an anti-junta protest by students that was brutally broken up on November 17, 1973. Welch was 17 November’s first target. (The group continued to conduct terrorist attacks in Greece, including the murders of other American officials, until it was finally crushed in 2002.)

Estes reported the truth back to CIA headquarters: that Welch had been murdered by Greek terrorists after being publicly exposed by the KYP, the Greek intelligence service. His story was buried in the service of a more helpful political narrative.

After Welch’s murder, emotions were running high in the CIA station in Athens. On the night of the assassination, Estes had to restrain another CIA officer after he grabbed a pistol and threatened to seek revenge by killing the KGB’s Athens Rezident, Welch’s Soviet counterpart.

Welch’s murder hit Estes hard as well. He and Welch had come up through the ranks of the agency together, and by 1975, they were close friends who met to play chess every Sunday. Welch and Estes had previously served together in Cyprus, and they understood the island’s status as a battlefield in the long-running conflict between Turkey and Greece. While serving in Cyprus, Estes said, Welch had recruited the personal secretary of Cypriot President Makarios III to spy for the CIA.

Estes was eager to solve his friend’s murder, without waiting for the Greek police. At the time, he didn’t know about the new leftist 17 November organization since Welch’s killing was its first operation. Instead, Estes focused his investigation on a right-wing terrorist group.

He and other CIA officers in Athens grilled their local sources and found that a gunman associated with a Greek-Cypriot right-wing paramilitary group known as EOKA had left Athens on a flight to Nicosia, Cyprus, the day after Welch’s killing. The gunman was known to have killed people in Cyprus with a .45 handgun — the same kind of weapon used to kill Welch.

When he worked in Cyprus years earlier, Estes had recruited an EOKA hitman to work for the CIA. “When I left Cyprus, he told me that whenever the CIA wanted something done that it didn’t want to do itself, call me,” recalled Estes. “So, after Welch was killed, I sent a case officer to Nicosia to meet him and tell him that Ron Estes sent him.”

The CIA officer asked the Cypriot agent if he knew the EOKA killer who had flown from Athens to Cyprus the day after Welch’s murder. The hitman said he did. The CIA officer told the hitman to go meet the man and ask him if he’d killed Welch.

The hitman reported that, when he confronted the EOKA killer, the other man was so scared that he offered to plead his innocence to the CIA himself. An American case officer then met with the man in Laranca, Cyprus, where he passed a CIA-administered polygraph.

Estes’s conviction that Welch had been exposed by the KYP and murdered by Greek terrorists, and the fact that CIA officers were conducting their own murder investigation on the ground in Cyprus, were not made public in Washington at the time. That information would only have gotten in the way of the campaign to exploit Welch’s murder to discredit the Church Committee.

Photo: Bettmann Archive

By late 1975, Ford and the CIA were both worried about their public standing. The Church Committee’s disclosures of intelligence abuses had weakened the CIA, and the White House was concerned about the political impact of the committee’s disclosures on Ford, the first commander-in-chief who had never been elected either president or vice president. Ford had been the obscure House minority leader in 1973 when he was chosen as vice president under the 25th Amendment by then-President Richard Nixon and Congress. Ford replaced Spiro Agnew, who had been forced to resign amid a corruption scandal; he became president when the Watergate scandal forced Nixon to resign in August 1974. Ford was headed into a tough presidential election campaign in 1976, and he wasn’t even assured of winning the Republican nomination. He faced a formidable challenge on the right from former California Gov. Ronald Reagan, and so Ford was eager to prove his conservative bona fides.

Now, with Welch’s assassination, the White House and CIA quickly realized they had been handed a political gift — a martyred hero whose death they could lay at the feet of liberal Democrat Church.

Largely through innuendo, the White House and the CIA blamed the Church Committee for Welch’s death, claiming that its investigations had somehow led to his exposure.

It didn’t matter that Welch’s murder had nothing to do with the Church Committee. It didn’t matter that Estes had told CIA headquarters that the Greek intelligence service had leaked Welch’s name and address to the Greek press as revenge for U.S. policy in Cyprus. Largely through innuendo, the White House and the CIA blamed the Church Committee for Welch’s death, claiming that its investigations had somehow led to his exposure.

The day after Welch’s murder, Welch’s father, who had been living in Athens with his son, asked Estes to see if Welch could be buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Welch had never served in the military, so burial at Arlington would require a special exemption.

Estes says he cabled CIA headquarters about the request, and Ford quickly gave his approval. That led to a grand political moment, stage-managed by the White House.

A U.S. Air Force plane flew Welch’s body from Athens to Washington. Welch’s son, a Marine lieutenant wearing his dress blues, accompanied his father’s body on the flight. The plane delayed its landing, circling Andrews Air Force Base outside Washington for 45 minutes so its arrival could be broadcast live during the morning network television news programs.

Daniel Schorr, a CBS News correspondent who covered the event, wrote in his personal journal, which was published in Rolling Stone in 1976, that “the public relations people explain that the big cargo plane, already overhead, will stay in a holding pattern and land at 7 a.m. so that it will be available for live televising on network morning news programs. We do in fact carry it live on the CBS Morning News.”

Welch’s January 6, 1976, funeral service at Arlington was attended by Ford, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, and CIA director William Colby. No president had ever before attended the funeral of a slain CIA officer.

After the funeral service, Ford stood beside Welch’s widow while Welch’s coffin was placed on a horse-drawn caisson. “We watch, and film … the same caisson that carried the body of President Kennedy, the folded flag given to the widow by Colby,” wrote Schorr in his journal.

CIA director William Colby, third from left, stands with the family of Richard Welch at his funeral on January 6, 1976.

Photo: AP

“It is the CIA’s first public national hero,” Schorr wrote. “I have a sense that Welch, dead, has one more service to render the CIA. He will be turned into a symbol in the gathering counter-offensive against disclosure.”

While Ford, Kissinger, and Colby attended Welch’s funeral, the FBI was investigating a death threat against Church in retaliation for Welch’s murder, sent by a group calling itself Veterans Against Communist Sympathizers.

Another prominent Washington official also attended Welch’s funeral: George Herbert Walker Bush, who had just been nominated to succeed Colby as CIA director. Ford had chosen Bush after firing Colby, who Ford believed had cooperated too readily with the Church Committee’s inquiries. The opening battle between the White House, the CIA, and Church would be fought over Bush’s confirmation in the Senate.

Church saw Bush’s nomination as an effort by Ford to put a partisan hack at the CIA, someone who would do the bidding of the White House just as Congress was seeking to curb the agency’s abuses. Church viewed Bush’s nomination as a direct attack on the Church Committee.

The chance to be CIA director came at a critical moment in Bush’s career. Until then, he had a poor record in elected politics. He won a House seat from Texas and served two terms but then lost a campaign for the Senate in 1970. After that, Bush started to rise in the Republican ranks through a series of appointed positions. He served as chair of the Republican National Committee during Watergate, a job that forced him to make repeated public excuses for Nixon but earned him credit for party loyalty. He also served as United Nations ambassador under Nixon and as head of the U.S. Liaison Office in China under Ford.

Ford was considering Bush to be his running mate in 1976; the job as CIA director seemed like a stepping stone. But first, Bush had to get past Frank Church.

Even as he was still working on his committee’s investigations and reports, Church went all out to block Bush’s confirmation. On December 16, 1975, Church testified as a witness against Bush during his confirmation hearings before the Senate Armed Services Committee. Bush’s confirmation was “ill-advised,” Church told the committee, because of his partisan political background and because he had refused to rule out running as vice president in 1976. Church complained that the White House was using the CIA as a “grooming room” for Bush “before he is brought on stage next year as a vice presidential running mate.”

But Welch’s murder quickly changed the political calculus of the confirmation fight in favor of Bush — and against Church.

The White House and CIA followed a subtle but effective strategy to use the Welch murder to help get Bush confirmed, while also poisoning the political climate for Church and his Committee. Immediately after Welch’s murder, the CIA sought to blame the Fifth Estate, a left-wing group based in Washington that published Counter Spy, a small left-wing magazine that had previously printed long lists of CIA officials’ names, including Welch’s when he served in Peru. Agency officials also blamed Philip Agee, a former CIA officer who had just published “Inside the Company,” a controversial book that had listed the names of hundreds of CIA officers and agents.

Many observers saw the CIA’s efforts to blame Counter Spy and Agee as a way to shift the blame for Welch’s murder from Greek terrorists to the CIA’s American critics. And if the public inferred that those American critics also included Church and his committee, so be it.

Conservative pundits quickly made the link explicit. In early January 1976, right-wing columnist Smith Hempstone wrote that the blame for Welch’s murder should be shared by “the congressional committees that for nearly a year have been holding the CIA up to ridicule and verbal abuse.” Around the same time, an anonymous, pro-CIA newsletter, the Pink Sheet, called Welch’s murder “a tragic reminder of a very basic truth: There are individuals and organizations in this country whose activities are aiding the enemies of the U.S. Are we to be impotent against such fifth columnists in our midst? Please write to your congressman and senators and ask what they propose to do about this increasingly dangerous problem. Instead of harming our internal security agencies, Senator Frank Church and his colleagues should be investigating outfits like the Fifth Estate.” The Pink Sheet’s diatribe was included in CIA files and publicly released by the CIA among other documents declassified in 2004. It is not clear whether the newsletter was published by someone affiliated with the CIA.

Meanwhile, former CIA officers began to make themselves available to the press to attack Church. One of them, Mike Ackerman, told reporters that the Church Committee shared the blame for Welch’s death, adding that the committee should have conducted its investigations without publicly disclosing agency operations.

New York Times columnist Anthony Lewis saw through the unfolding White House-CIA strategy.

“Understandably, the Welch case has brought to a boil the resentment felt by CIA veterans at critics of the agency,” Lewis wrote. “But it is another matter entirely to use the murder of Richard Welch as a political device, as President Ford and his national security assistants are evidently trying to do now.”

Colby’s “denunciation [of Fifth Estate] plainly had a larger purpose: to make the case that the CIA needs more secrecy in general than it has been getting lately,” Lewis wrote. “President Ford and his colleagues, judging by their recent comments, hope to prevent any thoroughgoing reform of the CIA. They will use the Welch case to that end, in particular to resist limits on covert action and to reduce congressional scrutiny.”

The Washington Star’s Norman Kempster agreed, noting that “only a few hours after the CIA’s Athens station chief was gunned down in front of his home, the agency began a subtle campaign intended to persuade Americans that his death was the indirect result of congressional investigations and the direct result of an article in an obscure magazine. The nation’s press, by and large, swallowed the bait.”

The campaign by the White House and the CIA to exploit Welch’s murder ensured Bush’s confirmation as CIA director. On January 27, 1976, Bush sailed through the Senate on a vote of 64-27. Ford made only one concession to the Senate before the vote: He announced that Bush would not be his running mate in 1976.

Four years later, Bush was elected vice president on the ticket with Reagan.

The false narrative that Welch had been murdered because of reckless disclosures in Washington remained powerful for years afterward, ultimately leading to legislation that made it illegal to publish the names of covert CIA officers, a law that has since often been abused by the government to crack down on whistleblowers and dissent.

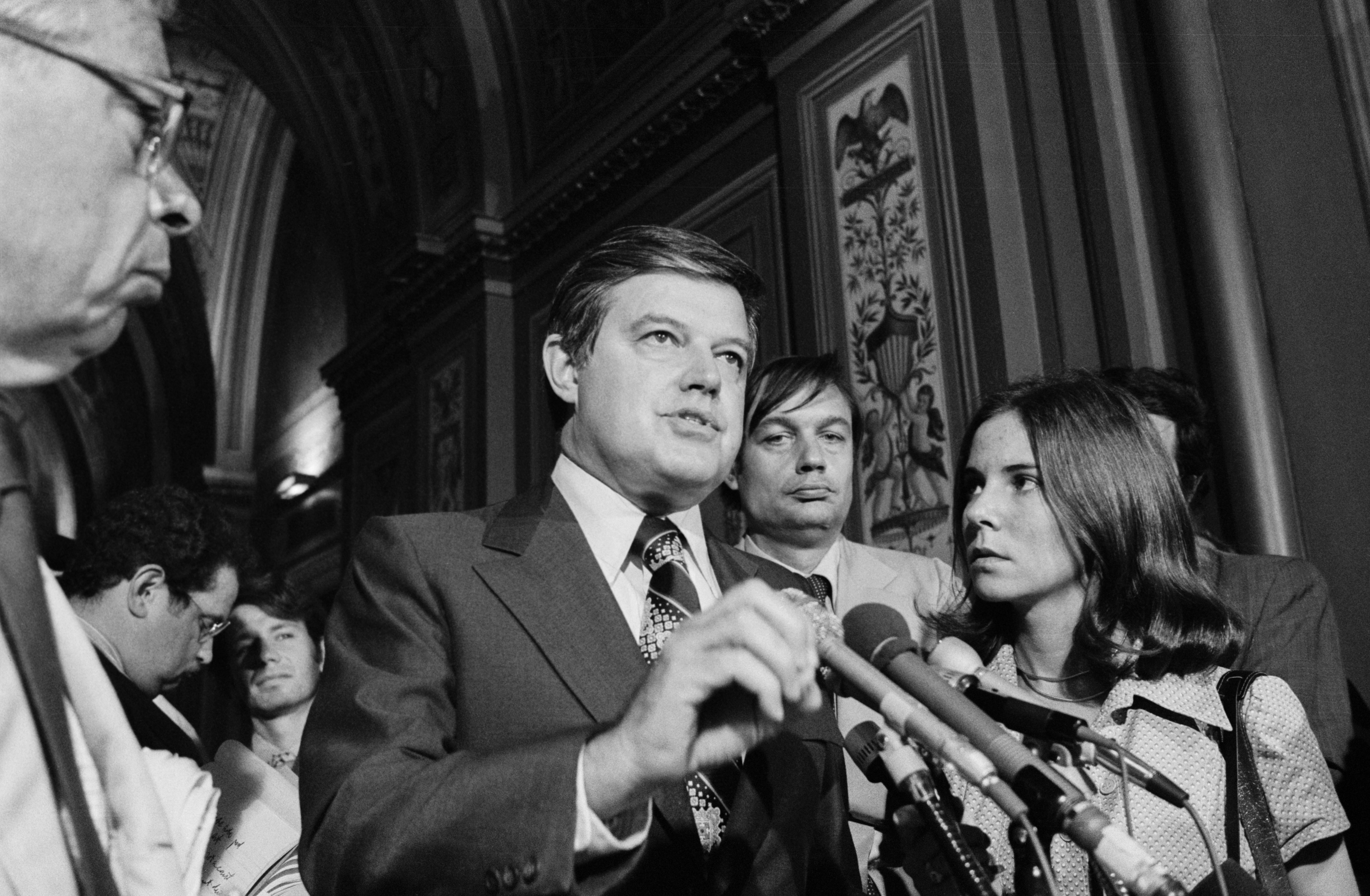

Central Intelligence Agency Director William Colby, left, arrives for questioning by the Senate Intelligence Commitee accompanied by George Cary, legislative counsel for the CIA, on May 21, 1975.

Photo: Bettmann Archive

After Welch’s murder, public support for the Church Committee waned. Church was stunned by the sudden reversal of the political climate and angered that Bush continued to push the false story around Welch’s killing even after he became CIA director.

During one closed hearing of the Church Committee soon after Bush had been confirmed, “Bush blurted out, ‘You were responsible for Welch’s assassination,’” recalled Fritz Schwarz, the Church Committee’s chief counsel. “It pissed off everybody. We forced Bush to apologize during the hearing.” Still, the Bush family continued to push false narratives about the Welch murder for years. In the 1990s, Agee, the former CIA officer, sued Barbara Bush for libel after she wrote in her memoir that Welch had been killed after Agee’s book blew his cover. The suit was dropped in 1997 after Bush acknowledged that Agee’s book was not responsible for Welch’s assassination.

Meanwhile, Church also had to convince other senators, whose support for his committee was wavering in the face of the White House and CIA disinformation campaign, that his investigation was not responsible for Welch’s murder.

“One of the things we did was tell other senators that we didn’t reveal Welch’s name,” recalls former Church Committee staffer Loch Johnson. “We had to make it clear to other senators that we had nothing to do with it.”

The controversy over Welch’s murder hit just as Church was about to launch his own bid to run for president in 1976. After the Church Committee had completed its investigations, Church announced his candidacy in March 1976. But by waiting until the committee’s work was done, Church started off far behind the front-runner for the Democratic nomination, former Georgia Gov. Jimmy Carter. Still, Church surprisingly won several primaries before dropping out and became a leading contender to be Carter’s running mate. When Carter instead chose Walter Mondale, a Democratic senator from Minnesota, Church began to suspect that CIA officials had worked behind the scenes to torpedo his selection. Church confided to his son that, just before the Democratic convention in New York, he’d gotten a call from the CIA saying the agency had been told that The Economist magazine was going to publish a story revealing that the Church Committee had been infiltrated by the KGB.

“Can you imagine any rumor more certain to spook a presidential candidate than that his prospective vice president has overseen an operation which was infiltrated by the KGB?” Church told his son, Forrest, who recounted the conversation in his 1985 memoir.

It turned out that the reporter the CIA had told Church was writing the story did not exist, and no story was ever published. “Church’s feeling that he had been sandbagged by the CIA might have been an illusion,” Forrest Church wrote. “One thing is certain, however. There is no member of the Senate whom the leaders of our intelligence services would have less preferred sitting a heartbeat away from the presidency.”

Former Church staffer Peter Fenn corroborated that account: “We talked a good deal about the CIA torpedoing him.”

The CIA’s hatred of Church didn’t end in 1976.

In 1980, Church was facing a tough reelection campaign in Idaho. As the election loomed, Rep. Steve Symms, a hard-right Republican who represented Idaho’s first congressional district, appeared the most likely candidate to run against him. Symms, whose family owned a large fruit ranch near Caldwell, Idaho, had been plotting to take on Church for years. He had even urged Bob Smith, his friend and chief of staff, to run against Church in 1974 as a stalking horse.

But just in case Symms had any last-minute doubts, James Jesus Angleton, the CIA’s former chief of counterintelligence, stepped in to give him a push.

Angleton felt he had been humiliated by being forced to testify in public before the Church Committee, and Church was at the top of his personal enemies list. In the late 1970s, Angleton, who was originally from Idaho, began meeting with Symms to convince him to run against Church.

“He was from Boise, and he really despised Frank Church,” Symms said in an interview. “He used to come over to see me in the House,” he added. Angleton would recount to Symms all the damage he claimed Church had wrought on the CIA, Symms said, and then Angleton would say, “You should run against Church.”

“I got exposed to that [intelligence] stuff through Angleton,” Symms added. “I still remember him coming over to my office and sitting on my couch, and he would smoke one cigarette after another. He would kind of put his leg up and talk to me on intelligence. He wanted Church defeated.”

Symms beat Church in 1980, which was cause for celebration in CIA circles.

“After I won the Senate race, I was invited to a party at someone’s house and I was just about the only person there who was not former intelligence,” Symms recalled. “It was quite impressive to meet all these people and see how deeply they all despised Church.”

This article was adapted from “The Last Honest Man: The CIA, the FBI, the Mafia, and the Kennedys — and One Senator’s Fight to Save Democracy” by James Risen with Thomas Risen, which will be published on May 9, 2023, by Little, Brown and Company, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc. Copyright © 2023 by James Risen. All rights reserved.

This content originally appeared on The Intercept and was authored by James Risen.

James Risen | Radio Free (2023-05-09T10:00:16+00:00) How the Murder of a CIA Officer Was Used to Silence the Agency’s Greatest Critic. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2023/05/09/how-the-murder-of-a-cia-officer-was-used-to-silence-the-agencys-greatest-critic/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.