I’m living in Rotterdam this year, and I was just watching your film ?O, Zoo! this morning. It was funny to see Holland in a film of yours from the ’80s, since I associate you with Ontario, where you were a professor of mine.

Yeah, that was a great trip. I spent that time on the set with Peter Greenway’s project. I met Greenway at the Grierson Film Seminar in Canada. He came and showed his film The Falls, which I really liked. I was invited to the set of his film A Zed & Two Noughts. For British people, it’s clear what the “Two Noughts” means! I was confused until he explained that it spelt Zoo. “?O,Zoo!” was my response, and it became the title of my film, ?O,Zoo! (The Making of a Fiction Film). All the punctuation in the title suggests that communication is as much about how things are said, as what is being said. The content is affected by the form.

Anyway, he said I could hang out on the set and shoot what I wanted.

That’s so cool. Can you tell me about Film Farm?

At the Grierson seminar, I learned about the power of “the retreat”! The Film Farm was born out of that idea. First, we needed a place to be away, a utopian place in a sense. People come and leave their jobs and kids behind, so they can focus on their own art and self. They’re taken care of, in terms of getting fed and all the basics. They’re in an experimental environment with creative individuals and go through a program of workshops and screenings.

We ask that you do not come to Film Farm with a script or idea. I say, “The idea is in you, and you’ll find it here.”

We did a Film Farm workshop at the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen, which was a fantastic experience. At the end of it we showed some of the films at the festival.

So, I’m getting back into in-person workshops. The themes of these workshops have mostly been surrounding flower processing, in a way that’s connected to the place “you stand,” exploring local flora and environments.

I did a workshop in Dawson City, Yukon, which was really interesting because we’d never used lichen (fungus), and other different kinds of northern plants for processing film.

Flower Processing Workshop at KIAC, Dawson City, Yukon 2022

We used 12 different plants and they all worked. This is kind of a new process, but it goes back historically to artists like Anna Atkins, a photographer who invented this type of process, with the idea of using light and the chemistry of flowers to create a photographic image either on photo paper or celluloid. The ecology of using plants that are blooming at the time and place where we’re processing film is what’s been exciting me lately, both in terms of my teaching and my own filmmaking.

Film Farm has also been hosting workshops in collaboration with Saugeen First Nation. The Elders have taught us medicinal aspects of plants, while we are teaching artists, through Saugeen Takes on Film workshops, about how to process film with plants. One of the Saugeen artists will be helping us teach in the next rendition of Saugeen Takes on Film.

Saugeen Takes on Film 2018: Bottom Natalka Pucan, Kelsey Diamond, Sharon Isaac, Top Debbie Ebanks Schlums, Gail Maurice, Terra Long, Philip Hoffman, Taylor Cameron, Emily Kewageshig, Adrian Kahgee

It can be really joyous to spend time with artists who want to work together and develop a more sustainable hand-made process.

What part of a plant is involved in developing the film?

Plants contain phenols and hydroquinone which are acids. Hydroquinone is used in cosmetics to clear blemishes from your skin. So if it can do that, it can do quite a bit with taking the exposed silver-halide crystals in the photographic emulsion and resolving it into metallic silver in a photographic sense. But you have to extract it from the plants by boiling it down, and then you mix it with vitamin C powder (ascorbic acid) and washing soda (sodium carbonate). The idea of it being household ingredients, you know, it can be done anywhere really. You just need the film.

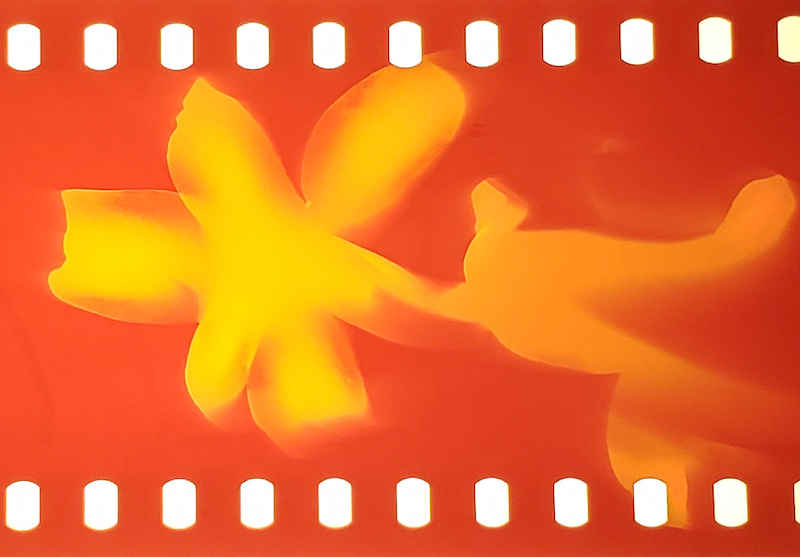

The other thing that’s been developing is this process called phytograhy (find recipe here). Thinking about Man Ray, his photogram work involves putting your film down in the dark, laying objects on the film, and then flashing it with light. You get the outline of a flower for example, just the outline.

Photogram by Philip Hoffman & Alexander Granger

Whereas phytography works with the inner chemistry of a plant. So you put the plants on the film and have it in the sun. The acids from the plants make all these wild patterns. After an hour, you rinse off the plants in water and place the film into fixer for a few minutes, or you can use salt for around 24 hours. The fixer or salt takes away all the silver halide crystals that were not touched by the plant or flower, so that part goes clear. That is why you still get the outline of the leaf or flower, like in a photogram, but it has a unique vibrant look.

Phytogram by Philip Hoffman

I like to think of it as if the photogram is the body, and the phytogram is the soul.

What kind of film do you use for that?

You use black and white film but you get color because of the internal chemistry of the plants. It all depends on the heat of the sun, the brightness, and the length of time. You can also use color film, it usually takes longer to develop.

With film especially, there’s so much industry versus art form. How have you stayed grounded in the art form of it while balancing it with being in the industry?

At the beginning I was in the industry working as a cinematographer. At the same time, I was teaching part-time film and making films of my own. I found that just teaching and my own filmmaking worked best.

The films I was making could be supported through small grants, and my life could be supported through teaching. Really, I think a lot of artists need a way apart from their practice to make enough to live on.

My art making is something that has to be protected. So, after college I looked for a job that couldn’t control me. I kind of did some industry stuff, but it sucked everything out of me. So I just worked at a wood plant. I cut wood so that I could continue to make films. I knew that what was important for me was to develop my own work in the way that I wanted to, rather than being pushed this way and that way through sponsors and producers.

What’s your process of grounding yourself in your artistic zone?

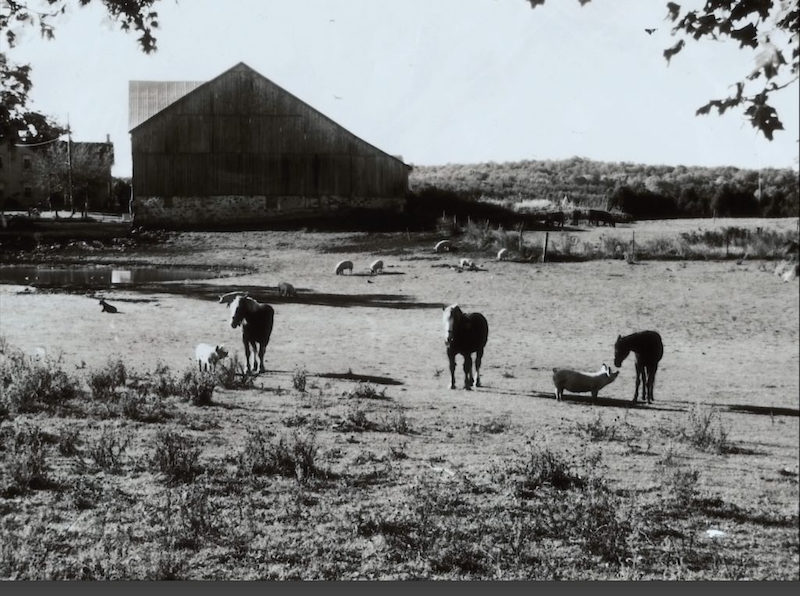

Grounding myself comes out of everyday life. I think it’s thanks to all kinds of relationships. In my film Vulture, I’m filming the farm animals that are next door, and following them over two years. I’m interested in the way that they have relationships with each other and the interspecies communication that ensues. In fact, in the film there’s a scene of a pig suckling a cow. So there’s this complex world going on in the barnyard that we don’t watch so readily when we drive past them on the highway.

I was completely submerged in that project for a couple of years. I was collecting images and processing the film using the flowers that were blooming at the time of the filming, and then I finally decided it was time to put something together. I usually create a picture of what the film could be. Maybe in an emblem or a symbol or something, and then I start to edit.

It sort of develops incrementally. Vulture took a “zen” approach. Every time I shot, it was a kind of performance because I didn’t know what the animals were going to do. It was exciting. I was also working on a film with my uncle who lived in Kitchener. We worked together on it for a long time. That project is much more personal and autobiographical. It satisfies other kinds of needs that I have, and comes from a desire to connect with my uncle again.

A lot of your films are like a diary. How would you describe it?

That’s the start of it. Yes, collecting is like making entries in a diary. I think there’s a point where it turns into, let’s say, fiction. In the sense that I have to put it together and create the work.

All storytelling is fiction. I would say all documentaries are fiction, because it’s coming from a certain perspective. If we both observed the same scene, we would have different stories to tell about it! Right? There really isn’t an objective truth.

With diary filmmaking and capturing life’s truths abstractly, has there been anything that’s been impossible to capture?

When you’re working with photography, what you learn most is that there’s a lot of things left out when you photograph something. I think from then, I always knew that I had to create something, some other kind of experience for a viewer that might take them away from what is physically on the screen — from the actual material. And that’s done through juxtaposition of narrative or images, or a certain effect.

Film allows us to organize time in various ways. Which the mind does as well. When we imagine things, it takes us somewhere else. So film is the perfect blend of something we see with our eyes, and something we see with our mind or body.

Throughout your career, have you had to battle self-doubt?

I’m on my own path and I’m making films a certain way. Things change in the world and you want to adjust, but it has to be real, how you adjust.

So, there’s doubts on what projects to do… There’s a film that I mentioned, with my uncle, that I’ve been working on for over 5 years. I’m thinking it can sit on the back burner until it feels right. There’s many different versions of it. I have doubts on whether it should go to an audience. Maybe I’m just doing it for myself. I’m in a place now where I think I know how to shape it in a way that could work for an audience. It’s challenging because it deals with homelessness.

I think I can get at that really well in a film that’s personal and connected. My uncle taught me accordion and took me fishing… and then over the years, he had some family and undiagnosed mental issues. He would never go to a doctor or anything like that. So, my whole thing of working on it biographically is questioned. Because I know it means a lot for me to do this now that he’s passed away. But what does it mean now? What does it mean for him, in his memory?

I want to show how brilliant he was and how people living on the street have lives, and they’re more than just this cardboard cutout that society makes them out to be. If you can’t film this, then who’s going to tell that story? And if they can’t tell their own story, and if the story they’re assigned when they’re on the street is the same story of, “Oh, they’re just hopeless.” You know, all these things that society says about them. But you know, I’m still in the middle of that.

How do you approach sharing your work?

As I get older, I find myself less eager for attention. I just continue to make my films and if people want to see them, they want to see them.

I had a screening with my sister Philomene and Janine, my partner, and it was a great night, you know? Philomene played a great piece of music that she just wrote… you can’t beat that. I think that stuff can get lost if you spend too much time on things like going to every festival and trying to make deals. So, I think I’m satisfied with this approach.

What does failure mean to you?

To me it’s exciting when something goes wrong. So-called wrong. It means that something has happened from the outside.

Part of the idea of “process cinema,” is that there is no failure. If something goes wrong, there’s a reason for it. Or you might as well make a reason for it and see what you can learn from it. So I think failure would be not recognizing that. Not recognizing that you don’t have control over everything. Thinking that failure is a problem is a problem.

There’s a thing of failure with the body, as you get older, that becomes something to worry about. Things have started failing, you know? It’s hard because your body is this thing that’s been working pretty well, and suddenly there’s things that are going wrong. But my film Deep 1, the one I’m working on, ends in a barrage of decay, which happened quite by accident. I left a piece of film in the wash which still had the residue of the Hyacinth developer in it. I left it there for a week or two and it just started breaking apart in decay. So the end of Deep 1, it’s just gorgeous. The world is just decaying.

So, to embrace the decay… How do you embrace decay when it’s your own body? I think that’s way more of an urgent sense of failure. Because everything’s built on that… So that’s something that I’m trying to understand now. But you know, ups and downs, right?

Do you have any advice for people who have knowledge and want to figure out how to share it through workshops?

Start with trying to figure out how to host workshops in a more friendship-oriented way. “We’re gonna do this at the house,” and, “Tomorrow we’re gonna develop film with flowers,” and, “Who wants to come over?” Call a few friends. I think that’s a good way to start.

I started Film Farm first at Sheridan College, they had a continuing education type program which I had managed to get a workshop booked into. They did some advertising which helped to find a group that was interested. So I think sourcing a few people that are interested in what you’re organizing who you can work with… You’re working with people that you want to be with. That has proven to be the most important aspect of group activities for me. You’re not collaborating with someone because they’re so skilled, but you’re doing it because you want to be with them. That’s the best way to create community.

How have you managed through moments of instability over your career?

At the start of my career, when I was teaching at Sheridan, it became too much. I was teaching five courses per term, I was exhausted. I started the Film Farm around then, which kept things going, but it didn’t make the teaching less overwhelming. I had a partner who passed away around that time as well, which obviously was difficult.

I definitely used film to kind of get through that. My own personal filmmaking was a good companion at the time and connected me back to my partner, who was only there in film and sound, and of course my imagination. So it took five years to make What These Ashes Wanted and I think making that film was a huge part of my grieving process. I think I came out of it with a better understanding, and less repressed about things. You always have some repression, I’m sure. That kind of experience lives in you to great depths.

When you’re going through challenges and making a film at the same time, is doing this creative thing a direct part of how you’re healing or is it more of a practice that just happens naturally beside it?

I think my filmmaking practice is intuitive. It becomes like eating and drinking and everything else. It’s part of survival and I think you just do it without really thinking about it too much. It’s just something that you have to do. I knew in my first films that I like this idea of using film to understand something about my life, and that fit because in the early years I was trying to figure out who I was!

In my first works, when I made road films, I came up with a slogan that when I’m on the road, I forget about myself. That’s great because you’re just kind of waiting for the next thing that crosses your frame, on the road. That’s a thing to live by for me, is just getting into the game. Like hockey or any sport you just get into the rhythm of the art, of passing the puck and shooting it. It’s not aggressive, it’s just getting into the rhythm of the game.

In ?O,Zoo! you were filming publicly. Do you have an openness towards the fact that while you’re making something personally in public, it becomes something for everyone around to possibly be involved in?

Yeah. For example those two Dutch boys in ?O Zoo!. They were very excited that I was making a film and they wanted to be part of it. I asked them to tell me about the animals and taped their audio. The thing is with film, it doesn’t stop. The relationship that started with them continued. I told them it might show in the Rotterdam Film Festival and they were very excited. I kept in correspondence with them. The things that are inside your frame are also outside your frame and in your life.

I remember saying to them, “I don’t think I’ll be able to come to Holland to show my film.” And they said, “You gotta try!” I’ll never forget. I kept that in my mind. They got all dressed up. It was a big screening in a theater, and they were there giggling away at themselves on the screen! Then years following that, they contacted me. As time goes on, sometimes those people become your friends for life, and other times they just pass by. Life continues. It’s encouraging. Your art becomes bigger than yourself.

Philip Hoffman Recommendations:

Horses (album, 1975) by Patti Smith

Poets (1998) by The Tragically Hip

Habits for your body like walking, skating, climbing, and swimming.

Habits for your mind like cooking, driving, playing accordion, and meditating.

This content originally appeared on The Creative Independent and was authored by Tiana Dueck.

Tiana Dueck | Radio Free (2023-06-16T07:00:00+00:00) Filmmaker Philip Hoffman on why it’s exciting when things go wrong. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2023/06/16/filmmaker-philip-hoffman-on-why-its-exciting-when-things-go-wrong/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.