ANALYSIS: By Richard Naidu in Suva

It has been six months now, but I have to make a strange admission. I miss the laughs I used to get over the pseudo-authoritative pronouncements of Fiji’s former attorney-general Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum (pictured).

I recall that he got a bit over-excited in January this year. That was when he decided to lecture the new government on “constitutionalism” and “rule of law”.

This was apparently without any reflection on how he and his FijiFirst party government had performed by the rule of law standards on which he was pontificating.

But in the last few days he decided to debate Deputy Prime Minister Manoa Kamikamica on the FijiFirst party’s 2022 financial accounts, apparently insisting that FFP was not insolvent.

This was never going to be an equal contest. Kamikamica is a chartered accountant. Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum, well — he isn’t.

You don’t need to be an accountant to read a balance sheet — or to understand the simple definition of insolvency.

It’s not hard. You are insolvent if you “cannot pay your debts as they fall due”. You can find the accounts of all the main political parties on the Fiji Elections Office website.

More cash than others

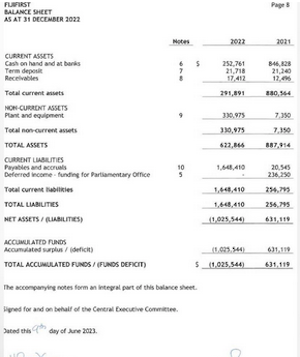

FFP’s balance sheet (see image) says it has cash and term deposits of more than $270,000 in the bank.

That’s pretty good. It’s actually more cash than all the other political parties combined. But FFP also has debts (called, in accountant-speak, “payables and accruals”).

These come to well over $1.6 million. Once you add and subtract all the smaller stuff, FFP is left with net liabilities of just over $1 million.

In other words, that’s $1 million that FFP, even if it sold everything it owns, still could not pay to its creditors.

That $1.6 million in debts “fell due” months ago. And FFP could not pay them as they fell due. So FFP is insolvent.

Why pretend otherwise? Luckily for FFP, there isn’t a simple legal way for a creditor to wind up a political party for not paying its debts. Presumably FFP’s unpaid suppliers have learned that bitter lesson a bit late.

Learning lessons

But we are all learning lessons about FFP. Six months ago it was all-powerful. Its leaders sat in taxpayer-funded government offices and did (pretty much) whatever they wanted.

They regularly lectured the rest of us on all of our failings and all the things we were doing wrong. They exuded competence. Fast forward to June 2023.

The same FFP — which previously ran a government that spends $4 billion a year — had been suspended because it couldn’t prepare its own accounts on time.

The deadline for submitting political party accounts is March 31 each year. That’s in the Political Parties Act. Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum presumably knew that because, after all, he “wrote the law”.

FFP’s accounts were not submitted by March 31. The Acting Supervisor of Elections (in stark contrast to her predecessor) did not fire off a suspension letter one day later.

She gave FFP (and some other political parties) an extension of time to put in their accounts. Six weeks later, FFP still had not filed its accounts.

And at that point even the most reasonable supervisor is entitled to be annoyed. That was when the suspension letter went out. Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum’s reaction at the time was the usual legalistic bluster unsupported by the facts. FijiFirst, he said, had not been afforded “due process and natural justice”.

Failed to meet deadline

He did not elaborate. And what could he say? His party had been given a six-week extension of time and still not met the deadline under the law he had himself drafted. And then we found out.

FFP was deeply in debt — and presumably too embarrassed to tell the rest of us. If it hadn’t been suspended, we would probably still not know.

What else can we learn from the accounts of the former ruling party? We can see from its balance sheet that it began 2022 with (cash and term deposits) more than $860,000 in the bank.

That’s the sort of money other politicians could only dream of. At that time the People’s Alliance and National Federation Party, between them, had less than $20,000.

However FijiFirst then went on to spend $4.2 million — or more accurately, it ran up debts of that amount, and now it has to find $1.6m to pay off those debts.

That is because FFP raised only $2.2 million in donations. I say “only” — but that $2.2 million was twice as much as the three parties now in government could collect.

More lessons

There are other, bigger, lessons to learn from all of this — lessons about money and politics. What was FFP thinking as it threw around the cash in the 2022 election campaign?

Who would spend $1.6 million they didn’t have? The answer — a party that thought that, as long as it could win, the cash would keep rolling in.

No political party in Fiji’s history has ever had millions of dollars to spend.

And no political party in Fiji has ever cashed in on its political power as cynically as FFP did in the past 10 years. It was FFP that made the laws on electoral funding for political parties.

Companies were not allowed to contribute — only individuals and only up to $10,000 each. All donors had to be publicly disclosed — this included someone who put $2 in a bucket during a soli.

SODELPA leader Viliame Gavoka famously commented on how the laws required his party to issue a receipt for selling a $1 roti parcel. FFP of course, did not have to bother with the small stuff.

Soli? Roti parcels? Why bother when you can just wait for the $10,000 cheques? And the cheques rolled in — with embarrassing enthusiasm.

Early donor lists

Many of us saw the early FFP donor lists when they were published. Prominent business families fell over themselves to write their $10,000 cheques.

Of course, these cheques were from “individuals”. Those individuals were company directors, their spouses and even their under-age children, even if those children (and probably some of the spouses) didn’t have bank accounts to write cheques from.

You would hear from other, less enthusiastic, business people about invitations to FFP fund-raisers. You went — and you took your chequebook with you — because if you didn’t, well…

One business man complained to me: “If I pay, I get to talk to them — but they don’t do anything about my business problems anyway.”

Fiji is not the first country to encounter unhealthy problems about money and politics.

These create challenges in every democracy. In Fiji’s so-called “true democracy”, the rules about who donated money were supposed to be transparent.

The Political Parties Act originally required the Supervisor of Elections to publish the names of people who donated to political parties. But as FFP’s donors squirmed with discomfort under the spotlight of social media, in 2021 FFP quietly changed the law — buried, of course, in one of those Bills that would be rushed to Parliament on two days’ notice and rushed through the infamous Standing Order 51.

The law change meant that those party donor lists still had to be disclosed to the Supervisor of Elections — but the Supervisor no longer had to publish them in the newspapers.

Climate of political fear

Of course, in the climate of political fear that FFP actively promoted, that created a separate problem.

The ruling party always collects the millions. But the opposition parties would have to work much harder to collect their cash because no one with any serious money wanted to be identified on those disclosure lists as giving money to the opposition.

Because, even though the Supervisor of Elections no longer had to publish those lists, any member of the public could still inspect them.

Most Fiji citizens might not know that. But the one person who would know that was the general secretary of FFP — also the minister for elections, attorney-general and minister for economy.

Now, however, for the first time since 2014, we can do something about our money-and-politics laws.

Those laws need to be reviewed, with a strong eye on the lessons of the past.

But the most critical lesson is probably not about those laws. It is about the climate of fear that enabled one political party to raise millions of dollars to keep itself in power while keeping all of its opponents out of cash.

Some good news?

Finally, for diehard FijiFirst supporters — a small spot of good news in those accounts. Apparently FFP still has 6120 “promotional sulu” in stock.

The sulu, according to the accounts (Note 11), have been “fully expensed”. This is because “realisable value cannot be determined with reasonable accuracy.” This is the way accountants say: “We don’t think anybody wants them so we can’t put any value to them.”

Perhaps to show their loyalty, FFP’s fans could buy the sulu to pay off the $1.6 million debt. This would cost only $270 per sulu. Just thought I’d try to help.

Richard Naidu is a Suva lawyer who writes a regular independent column for The Fiji Times. He has enough sulu.

This content originally appeared on Asia Pacific Report and was authored by APR editor.