I’m writing this because I believe truth telling — my own bearing witness to just one BWS case in Lincoln County over the course of more than a year and a half — can be instructive to the reader.

I will say upfront that the experience here in Lincoln County has been far from a bed of roses for my friend, who is young (40), and is independent, strong and intelligent. But after those years of abuse by a drunkard, and then the 911 call last year, she thought she had finally unmasked the failures she kept beating herself up for and finding some safe space from which to spend time to change.

Is it possible for an abusive man — who had intimated murdering her would be easily covered up — to be rehabilitated? Can a man be restored — a man raised by a macho father; an angry arrested-developed male vociferous in his misogyny; a violent guy; and a big-time narcissist and alcohol abuser?

This is a story in many parts, and the survivor — my friend who was both victim and psychologically connected to the abuser — is still in the process of dealing with the outfall of suffocation, then calling 911, seeing the sheriff deputies respond, witnessing her husband struggle in handcuffs, and herself appearing in front of a grand jury who indicted the accused on more than 10 charges.

That was more than 10 months ago, and as I write this, the fellow is about to be released as part of a diversionary agreement, AKA a plea agreement. He will be in Judge Sheryl Bachart’s domestic violence special court.

This is a story of unending “to be continued” phases in her life, in her family’s life and her friends’ lives.

Getting people — victims, survivors, counselors, and others — to respond to a journalist’s question, both on the record and named, is daunting. “I can talk all day in group therapy with victims of domestic violence, but those are safe spaces,” said one counselor from Arizona with more than 30 years in the field of social work, including running so-called safe houses.

“But imagine me identifying myself in the newspaper, with my credentials and current place of work presenting myself as a feminist and pretty critical of the judicial, policing and social services fields in regard to domestic violence and how those systems treat the victim? I’d be pulled onto the carpet, for sure.”

Referring to a person who is going through the legal hurdles of fighting for her life by calling 911, “a victim” is not considered politically correct in feminist circles, one former woman’s studies professor (again, asking to not be named) said to me (I worked with her at Green River College years ago).

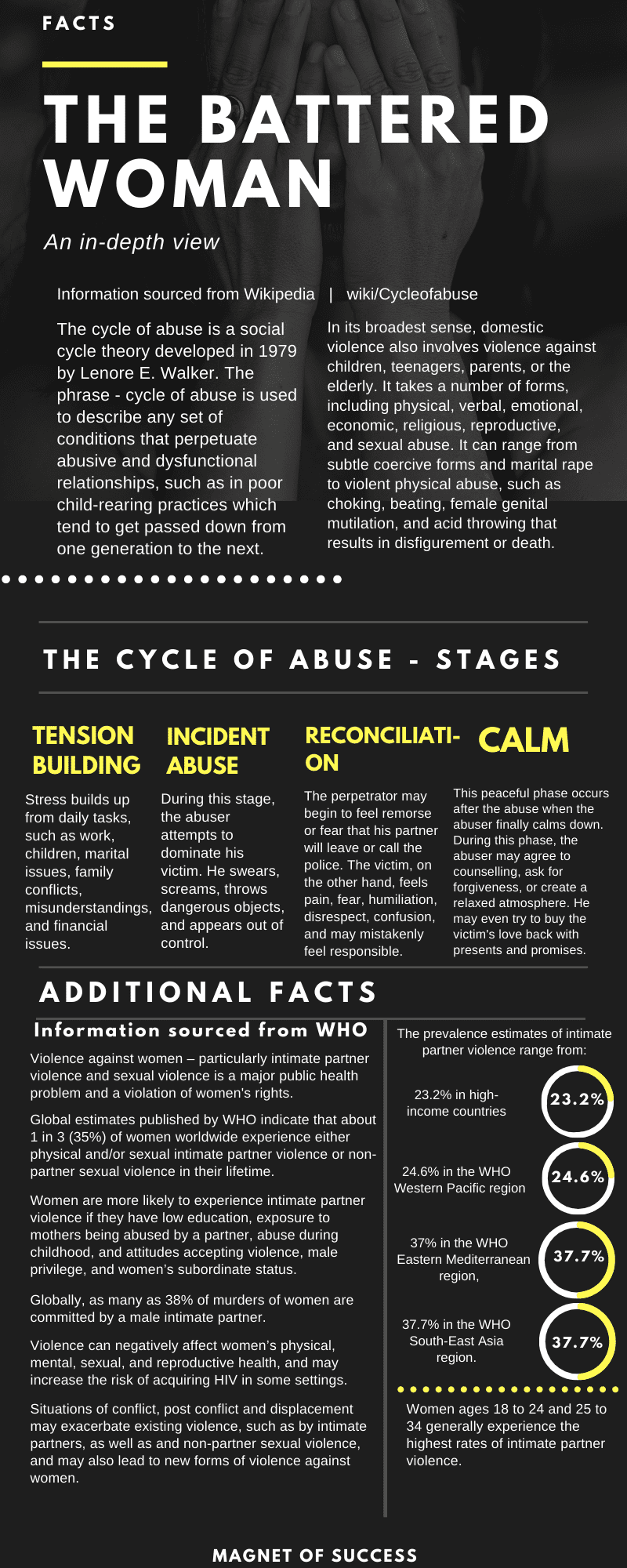

However, the woman who coined the term, “Battered Wife Syndrome,” believes using the word “victim” for a woman in the midst of the abuse even after calling the cops is correct: “Until battered women take back some control over their lives, they may not truly be considered survivors.”

“A battered woman needs to feel validated when she describes the abuse. This can be done by emphasizing the positive things she did to protect herself and her children if they were involved. Tell her that no matter what she may have done or said, no one deserves to be abused,” Walker wrote in the piece. “Be careful not to ask or even intimate that she might have done something to provoke the batterer. Such questions will not create the rapport that facilitates empowerment-nor do they create a safe space for the woman.”

My own experience with domestic violence spans decades as I worked the police beats early as a newspaperman (starting at 18) in Tucson for the college daily, and then continued with police beats for newspapers in Southern Arizona, West Texas and Spokane.

The crux of this self-referential three-part look at domestic violence survivors, and scrutinizing the systems in place that “deal with” the abused and the abusers, is my own experience working with this friend living in Lincoln County who in March 2022 reached out to me for assistance to leave her abuser.

I barely knew her then, but consider her to be a great friend of my wife and mine.

The fact she ended up in Arizona, with my own sister, a seasoned statewide social worker, Heidi Haeder-Heild, assisting her, that was not enough to break her out of the battered wife syndrome. She returned to Lincoln County a few months later, lured by the hope of a changed husband, entranced by the idea that she had changed and that change would convince the husband she was a worthy wife, friend, woman to never be put down, economically isolated and physically abused.

Those hopes ended with a 911 call she frantically made on a Friday night in November 2022.

+–+