SPECIAL REPORT: By Andreas Harsono in Jakarta

In December 2008, I visited the Abepura prison in Jayapura, West Papua, to verify a report sent to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on torture alleging abuses inside the jailhouse, as well as shortages of food and water.

After prison guards checked my bag, I passed through a metal detector into the prison hall, joining the Sunday service with about 30 prisoners. A man sat near me. He had a thick beard and wore a small Morning Star flag on his chest.

The flag, a symbol of independence for West Papua, is banned by the Indonesian authorities, so I was a little surprised to see it worn inside the prison.

He politely introduced himself, “Filep Karma.”

I immediately recognised him. Karma was arrested in 2004 after giving a speech on West Papua nationalism, and had been sentenced to 15 years in prison for “treason”.

When I asked him about torture victims in the prison, he introduced me to some other prisoners, so I could verify the allegations.

It was the beginning of my many interviews with Karma. And I began to understand what made him such a courageous leader.

Born in 1959 in Jayapura, Karma was raised in an elite, educated family.

Student-led protests

In 1998, when Karma returned after studying from the Asian Institute of Management in Manila, he found Indonesia engulfed in student-led protests against the authoritarian rule of President Suharto.

On 2 July 1998, he led a ceremony to peacefully raise the Morning Star flag on Biak Island. It prompted a deadly attack by the Indonesian military that the authorities said killed at least eight Papuans, but Papuans recovered 32 bodies. Karma was arrested and sentenced to 18 months in prison.

Karma gradually emerged as a leader who campaigned peacefully but tirelessly on behalf of the rights of Indigenous Papuans. He also worked as a civil servant, training new government employees.

He was invariably straightforward and precise. He provided detailed data, including names, dates, and actions about torture and other mistreatment at Abepura prison.

Human Rights Watch published these investigations in June 2009. It had quite an impact, prompting media pressure that forced the Ministry of Law and Human Rights to investigate the allegations.

In August 2009, Karma became seriously ill and was hospitalised at the Dok Dua hospital. The doctors examined him several times, and finally, in October, recommended that he be sent for surgery that could only be done in Jakarta.

But bureaucracy, either deliberately or through incompetence, kept delaying his treatment. “I used to be a bureaucrat myself,” Karma said. “But I have never experienced such [use of] red tape on a sick man.”

Health crowdfunding

His health problems, however, drew public attention. Papuan activists started collecting money to pay for the airfare and surgery in Jakarta. I helped write a crowdfunding proposal. People deposited the donations directly into his bank account.

I was surprised when I found out that the total donation, including from some churches, had almost reached IDR1 billion (US$700,000). It was enough to also pay for his mother, Eklefina Noriwari, an uncle, a cousin and an assistant to travel with him. They rented a guest house near the hospital.

Some wondered why he travelled with such a large entourage. The answer is that Indigenous Papuans distrust the Indonesian government. Many of their political leaders had mysteriously died while receiving medical treatment in Jakarta. They wanted to ensure that Filep Karma was safe.

When he was admitted to Cikini hospital, the ward had a small security cordon. I saw many Indonesian security people, including four prison guards, guarding his room, but also church delegates, visiting him.

Papuan students, mostly waiting in the inner yard, said they wanted to make sure, “Our leader is okay.”

After a two-hour surgery, Karma recovered quickly, inviting me and my wife to visit him. His mother and his two daughters, Audryn and Andrefina, also visited my Jakarta apartment. In July 2011, after 11 days in the hospital, he was considered fit enough to return to prison.

In May 2011, the Washington-based Freedom Now filed a petition with the UN Working Group on arbitrary detention on Karma’s behalf. Six months later, the Working Group determined that his detention violated international standards, saying that Indonesia’s courts “disproportionately” used the laws against treason, and called for his immediate release.

President refused to act

But President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono refused to act, prompting criticism at the UN forum on the discrimination and abuses against Papuans.

I often visited Karma in prison. He took a correspondence course at Universitas Terbuka, studying police science. He read voraciously.

He studied Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King on non-violent movements and moral courage. He also drew, using pencil and charcoal. He surprised me with my portrait that he drew on a Jacob’s biscuit box.

His name began to appear globally. Chinese artist Ai Weiwei drew political prisoners, including Karma, in an exhibition at Alcatraz prison near San Francisco. Amnesty International produced a video about Karma.

Interestingly, he also read my 2011 book on journalism, “Agama” Saya Adalah Jurnalisme (My “Religion” Is Journalism), apparently inspiring him to write his own book. He used an audio recorder to express his thoughts, asking his friends to type and to print outside, which he then edited.

His 137-page book was published in November 2014, entitled, Seakan Kitorang Setengah Binatang: Rasialisme Indonesia di Tanah Papua (As If We’re Half Animals: Indonesian Racism in West Papua). It became a very important book on racism against Indigenous Papuans in Indonesia.

The Indonesian government, under new President Joko Widodo, finally released Karma in November 2015, and after that gradually released more than 110 political prisoners from West Papua and the Maluku Islands.

Release from jail celebration

Hundreds of Papuan activists welcomed Karma, bringing him from the prison to a field to celebrate with dancing and singing. He called me that night, saying that he had that “strange feeling” of missing the Abepura prison, his many inmate friends, his vegetable garden, as well as the boxing club, which he managed. He had spent 11 years inside the Abepura prison.

“It’s nice to be back home though,” he said laughing.

He slowly rebuilt his activism, traveling to many university campuses throughout Indonesia, also overseas, and talking about human rights abuses, the environmental destruction in West Papua, as well as his advocacy for an independent West Papua.

Students often invited him to talk about his book.

In Jakarta, he rented a studio near my apartment as his stopping point. We met socially, and also attended public meetings together. I organised his birthday party in August 2018. He bought new gear for his scuba diving. My wife, Sapariah, herself a diving enthusiast, noted that Karma was an excellent diver: “He swims like a fish.”

The resistance of Papuans in Indonesia to discrimination took on a new phase following a 17 August 2019 attack by security forces on a Papuan student dormitory in Surabaya, Indonesia’s second largest city, in which the students were subjected to racial insults.

The attack renewed discussions on anti-Papuan racial discrimination and sovereignty for West Papua. Papuan students and others acting through a social media movement called Papuan Lives Matter, inspired by Black Lives Matter in the United States, took part in a wave of protests that broke out in many parts of Indonesia.

Everyone reading Karma’s book

Everyone was reading Filep Karma’s book. Karma protested when these young activists, many of whom he personally knew, such as Sayang Mandabayan, Surya Anta Ginting and Victor Yeimo, were arrested and charged with treason.

“Protesting racism should not be considered treason,” he said.

The Indonesian government responded by detaining hundreds. Papuans Behind Bars, a nongovernmental organisation that monitors politically motivated arrests in West Papua, recorded 418 new cases from October 2020 to September 2021. At least 245 of them were charged, found guilty, and imprisoned for joining the protests, with 109 convicted of “treason”.

However, while in the past, Papuans charged with political offences typically were sentenced to years — in Karma’s case, 15 years — in the recent cases, perhaps because of international and domestic attention, the Indonesian courts handed down much shorter sentences, often time already served.

The coronavirus pandemic halted his activism in 2020-2022. He had plenty of time for scuba diving and spearfishing. Once he posted on Facebook that when a shark tried to steal his fish, he smacked it on the snout.

On 1 November 2022, my good friend Filep Karma was found dead on a Jayapura beach. He had apparently gone diving alone. He was wearing his scuba diving suit.

His mother, Eklefina Noriwari, called me that morning, telling me that her son had died. “I know you’re his close friend,” she told me. “Please don’t be sad. He died doing what he liked best . . . the sea, the swimming, the diving.”

West Papua was in shock. More than 30,000 people attended his funeral, flying the Morning Star flag, as their last act of respect for a courageous man. Mourners heard the speakers celebrating Filep Karma’s life, and then quietly went home.

It was peaceful. And this is exactly what Filep Karma’s message is about.

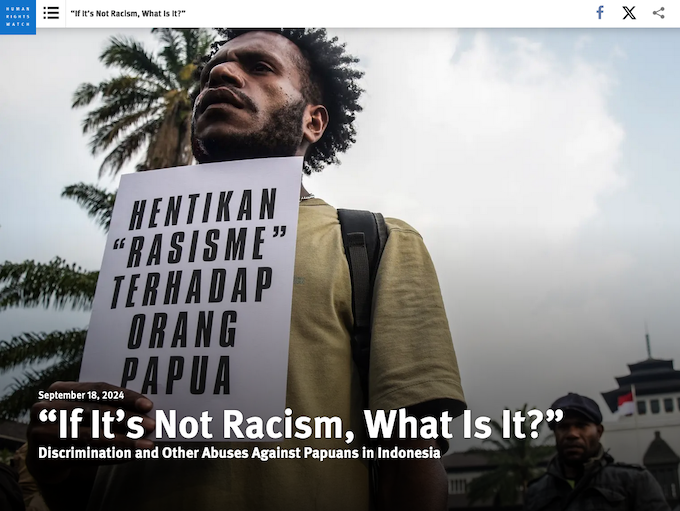

Andreas Harsono is the Indonesia researcher at Human Rights Watch and the author of its new report, “If It’s Not Racism, What Is It?”: Discrimination and Other Abuses Against Papuans in Indonesia. This article was first published by RNZ Pacific.

This content originally appeared on Asia Pacific Report and was authored by APR editor.

APR editor | Radio Free (2024-10-31T21:33:41+00:00) Filep Karma: A political prisoner who fought racism in West Papua. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2024/10/31/filep-karma-a-political-prisoner-who-fought-racism-in-west-papua/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.