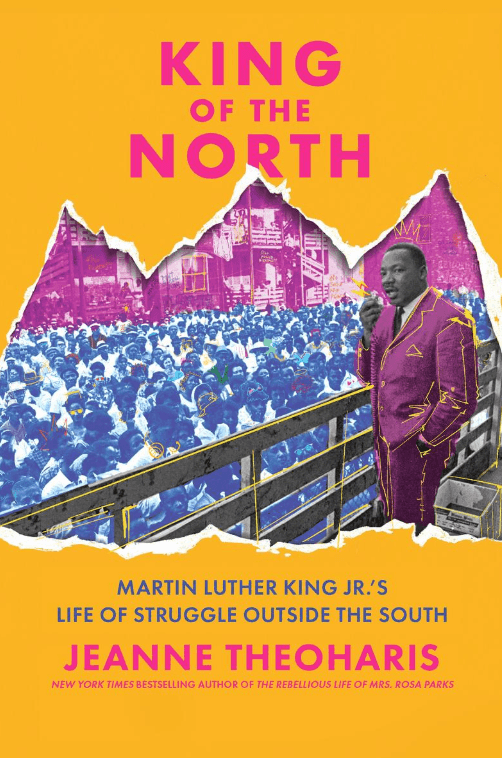

Image by Unseen Histories.

Eight Places You Need to Visit and Understand Chicago’s Black Freedom Struggle

Go to Montgomery, Alabama today and markers to the civil rights movement dot the city landscape: Dr. King’s house, the place where Rosa Parks was arrested, homes of other activists like E.D. Nixon and Georgia Gilmore, the site where the 1960 Freedom Riders were attacked. But come to Chicago and the markers to the city’s civil rights movement are few and far between–despite an incredibly robust freedom movement and a level of segregation that Dr King termed one of the “most segregated” in the nation in 1963.

In Marquette Park, there is a beautiful artist-designed memorial where civil rights marchers were assaulted by white mobs in the summer of 1966 but no mention of city officials’ long-standing attempts to keep the city segregated. The National Park Service has given landmark status to the Chicago church where teenager Emmett Till’s casket, lynched in Mississippi, was opened for the world to see. But the site of 17-year-old Chicago teenager Jerome Huey’s lynching that occurred in the city in 1966, the 1963 school boycott, and the slum apartment the Kings lived in remain unmarked.

This Southernification of King and the civil rights movement is a more comfortable tale. It erases the systemic, longstanding segregation and racial inequality endemic in Northern cities and marginalizes the robust, years-long movement in Chicago that Martin Luther King supported and then helped expand with the SCLC in 1965—movements that were ignored, dismissed, or demonized by most white Chicagoans, city leaders, and the federal government at the time. To tell that Northern story, to mark those places and reckon with that history, uncovers a more necessary if unsettling truth about this country.

Too often Northern racism and segregation are, as they were sixty years ago, dismissed as not systemic, a product of people’s preferences to live in communities that are not integrated. But even a glimpse of the history shows how city leaders, school officials, real estate interests, and outright violent racists colluded to maintain segregation and inequality in cities like Chicago.

Mayor Richard J. Daley’s home, 3536 South Lowe Avenue in Bridgeport. Elected mayor in 1955 and serving until he died in 1976, Daley would persistently deny the city’s segregation and, as persistently, work to maintain it, including in his own all-white neighborhood of Bridgeport. The mayor backed the building of massive housing projects to contain Black people including the segregated, seventeen-story Stateway Gardens and twenty-eight-story, 30-block-long Robert Taylor Homes projects. Stunned by the intensity of segregation, Martin Luther King called them “cement reservations”: Coretta, “upright concentration camps.”

The construction of the Dan Ryan Expressway was slated to go through Bridgeport but Daley changed the route so the expressway swerved into the Black southside community, destroying a vibrant section of Black Chicago. When two Black students attempted to rent a Bridgeport apartment, Daley let his neighbors run them out. When school desegregation activists marched on his house and his neighbors through bottles and rocks, he had the marchers arrested not his neighbors and defended his neighbors as “fine, hardworking people.”

Willis Wagon Protest at 73rd Street and Lowe Ave. School segregation wasn’t a happenstance either. School superintendent Benjamin Willis who served from 1956-1966, alongside school officials throughout the city, actively worked to keep the schools segregated. When the numbers of Black students increased, instead of letting Black students into predominantly-white schools with open seats, Willis bought trailers (which activists then named “Willis wagons”) to install at Black schools. The city also put many Black schools on double session days–one group of kids in the morning, another group in the afternoon. Black parents organized furiously. When meetings and marches had little effect, Black mother Rosie Simpson launched a protest of wagons being installed at 73rd street and Lowe Ave, laying down to block the construction. The protests there and at other sites and arrests went on for months. Comedian Dick Gregory was arrested; King went to the jail to show his support for Gregory and the other demonstrators.

October 22, 1963 “Freedom Day” school boycott: Board of Education, 1 North Dearborn Street. Growing tired of the city’s intransigence, activists including Simpson organized a school boycott. King met with them to encourage their action. Part of the rationale behind the boycott was the school system received money for each student’s attendance, so it would hurt their operating budget and underline the gravity of the situation. On October 22, a stunning 225,000 students—50 percent of the city’s total school enrollment (with numbers rivaling the March on Washington two months earlier)—stayed out of school to protest the lack of school desegregation and an end to the Willis wagons. Ten thousand students and parents picketed City Hall and the Board of Education, carrying signs reading “Willis Must Go” and “No More Little Black Sambo Read in Class.”

City Hall, 121 North La Salle Street. In July 1965, Chicago parents with the CCCO filed a complaint with the US Office of Education that the Chicago Board of Education had violated Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act—which gave the US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) the power to withhold federal funds if school districts continued to segregate. Chicago stood to lose over $30 million. The federal government requested a host of information: racial head counts of students and teachers, per-pupil expenditures in schools, average class size, student-teacher ratios, and the method of assigning teachers. But Willis and the Board of Education did not comply. And HEW learned Willis intended to use the federal money to aid middle-class white districts and procure more trailers.

As a result, on October 1, HEW withheld those $32 million in federal funds, finding Chicago schools in “probable non-compliance.” King telegrammed President Johnson praising the decision and enforcing the Civil Rights Act against Northern school systems. But the Chicago Tribune, alongside most white Chicagoans, found the decision “outrageous” and slammed “federal interference.” Furious, Mayor Daley got on a plane to confront President Johnson directly. Johnson capitulated and less than a week after it had withheld funds, HEW released the $32 million to Chicago.

The Chicago Freedom Movement in concert with SCLC doubled down in their protests over the next year. On July 10, 1966, over 35,000 Chicagoans braved the 98-degree heat for a rally and march to City Hall to publicize their demands. When they arrived, King taped the fourteen-point list of the movement’s demands to the door. Their demands laid out a detailed blueprint for addressing the city’s inequities, including enforcement of the 1964 Civil Rights Act against Chicago’s segregated schools; a civilian complaint review board to monitor the Chicago Police Department; a bargaining union for welfare recipients and ceasing of home investigations; a $2 state minimum wage; increased garbage collection and building inspections; and federal supervision of loans by banks and savings institutions.

1550 South Hamlin Avenue. The SCLC had joined the years-long Chicago Freedom Movement to build out a campaign against the city’s segregation, expanding the campaign in July 1965. In January 1966, to further escalate, the Kings moved into a $90-a-month North Lawndale tenement on Hamlin. When the landlord found out the Kings were moving in, he hastily fixed some of the building’s most glaring code violations. Still, the heat and refrigerator didn’t work. The food sold in nearby stores was often of poor quality and rats were plentiful. Working-class Black Chicagoans paid more for rent and living expenses and got smaller, more decrepit units with many more code violations than their white working-class counterparts.

1811 West Adams Street. The next month, on February 3, 1966, Andre Adams, a baby two days shy of his first birthday, was chewed to death by a rat. The infant was also severely malnourished, weighing only 5 pounds, 8 ounces when he died. Westside parents rose up in anger. These inhumane conditions—starvation, rats, buildings without heat—were “why we’re here fighting in the slums of Chicago,” said King, who called Adams’ death “as much of a civil rights tragedy as the murder of [Viola] Liuzzo” after the Selma march. Black parents had highlighted the rats and the health problems they had brought for years but were continually ignored by the city.

1321 South Homan Avenue. Scores of buildings in the westside and southside ghettos had numerous building code violations. One night, five families with 15 children came to visit the Kings to tell them about the uninhabitable conditions in their building–no heat in the dead of winter, rats in their apartments, and in some cases no running water. King went over to their building and was disgusted to see the conditions of the building, including a baby wrapped in newspaper to keep warm. Three weeks after Adam’s death, to expose “how bad the slum conditions were,” the SCLC with the tenants decided to engage in a rent strike where the family’s pooled their rent in a trusteeship through SCLC and the money was used to fix the furnace and the building’s electrical system. City leaders and the national press were outraged. The landlord took King and the SCLC to court. The judge ordered the trusteeship ended but didn’t find King guilty of a criminal charge–putting the building in receivership and ordering the landlord to fix the 23 code violations within the next month.

Jerome Huey lynching–25th Place and Laramie Avenue, Cicero. On May 25, 1966, 17-year-old Black teenager Jerome Huey set out for a job interview at a freight-loading company in Cicero. While waiting at the bus stop after the interview, he was attacked by four white men and beaten with a baseball bat so badly that his eyes came out of his skull. Huey died in the hospital two days later–a lynching in plain sight. One of the driving reasons the Chicago Freedom Movement began holding open-housing marches that summer into Chicago’s sundown neighborhoods like Marquette Park, Gage Park, and Cicero (where Black people worked but couldn’t live), was to break the fear and the city’s complicity in this segregation and racist violence.

But 59 years later, the site where Jerome Huey was lynched is completely unmarked. While most Chicagoans and indeed many Americans know the story of Emmett Till, Jerome Huey’s horrific death has been erased. “The North is not the promised land,” Coretta Scott King underlined. So the lack of historical markers in Chicago (and New York, Boston, Los Angeles, and Detroit) has significant consequences, not just for understanding the city’s past but for reckoning with the persistence of this inequality and where we must go from here.

Making this history visible for Chicagoans and visitors alike to encounter on a daily basis would expose how racial inequality persists, the mechanisms that keep it in place, and how we might begin to change this reality. It would demonstrate that segregation is a national problem, not one that can be dismissed as a regional aberration. Chicago’s role in upholding racism and the heroic people who fought for a different way must not remain hidden in plain sight.

A shorter version of this piece first appeared in The Chicago Tribune.

The post Marking Martin Luther King Jr.’s Chicago appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This content originally appeared on CounterPunch.org and was authored by Jeanne Theoharis - Erik Wallenberg.

Jeanne Theoharis - Erik Wallenberg | Radio Free (2025-03-21T05:58:03+00:00) Marking Martin Luther King Jr.’s Chicago. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2025/03/21/marking-martin-luther-king-jr-s-chicago/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.